by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 2, 2016 | Thoughts

It’s the second day of January. The carpet is still full of fallen pine needles, a straggler Christmas card just arrived in the mail, and the Christmas clearance section at Target is best described as “there appears to have been a struggle.” Two aisles over, cascades of pink and red hearts festoon the shelves. Valentine’s Day is 6 weeks away, yet the decor screams, “Let’s MOVE, people!”

2016 has barely begun and I’m already feeling the push of what’s next, hearing the faint scritch, scritch of anxiety scratching to be let in. Not this year. The 40’s have been described as the rush hour of life. We are busy with careers, tugged between growing children and aging parents, spread thin trying to maintain marriages, friendships, and waistlines. We run the treadmill, literally and figuratively, dealing with life in broad shallow strokes with little time to stop and dive deep.

My word for this year is savor. On Christmas morning, my sister’s family wakes gradually, enjoys a nice breakfast, and then opens presents one by one throughout the day. It’s not unusual for me to call late in the afternoon to wish them a Merry Christmas, asking if the kids liked what we sent. “Oh, we haven’t gotten to them yet!” she’ll say. “It’s not even dinner time!” I’m incredulous. At my house, we wake early, pillage the stockings, and whip through the bounty like Tasmanian devils. We are usually napping again shortly after lunch from the exhaustion of it all. This year, we reined in the frenzy and took our time, pausing to watch the pouring rain as it flooded the yard. It was a welcome change.

Maybe it’s a symptom of unfettered youth, this rushing on to what’s next. My ambitious and eager college student daughter is not even halfway through a semester before she’s planning the next. Every step is planned and scheduled, from semesters abroad to internships that may lead to post-graduation employment. She focuses on what’s around the corner, imagining life will be more exciting, stable, or less stressful when—. I tell her to slow down and enjoy where she is, but the truth is a couple of misty decades ago I did the same. I couldn’t wait to be an adult, unleashed and independent. I would have adventures and embark on a life that was, above all, interesting, the opposite of ordinary and everything I imagined my mother’s was. Life would start to be grand when I graduated, got a job, got married, once we had children, once they were out of diapers, once the business took off, once…

Now, a little further down the road, I see. The ordinary minutes of the ordinary days and years have blown by, consumed by something like 27,000 meals, 4,000 loads of laundry, and 14,000 diaper changes. Wiping the counters, feeding the pets, filling the gas tank, helping with school projects, taxiing to and from practices, church services, and friends’ houses. Teaching the littles how to write their names, ride a bike, drive. Reading The Seven Silly Eaters for the 85th time, wiping tears from scraped knees and broken hearts, gritting my teeth from a slammed door or the virtual door of headphones and a cellphone. Beach sand in our shoes, doctor visits, braces, and pet burials. Ordinary days. Not quite the world-changing adventure I’d imagined at 20, but an adventure, I think, just the same.

Truly, some of those days it was a struggle just to make it to the other side of morning. Many of them I wished for what was next because stories and diapers and teenaged angst were sometimes, honestly, less than riveting. Naptime, bedtime, date night. Now I just wish my mother were still here so I could tell her I get it. This is the adventure. This is the interesting. This was it all along. The sticky kisses, unshaven husband, car trouble, health scares, and bounced checks. Even the frustrations, hurry, and hurt. This is what my mother and my sweet friends who have left too soon no longer get to savor. This is what they clung so hard to and fought to stay for.

Savor means to taste and enjoy completely, which can only be done without hurry, without looking to the next bite before finishing the first. Always looking for what’s next, what we imagine to be our sav-i-or, reverses the natural order of things. It makes the foreground, the background, and we miss the gift of what’s now. If we deliberately, on purpose, slow down and take the “i” out of the equation, the “I” that worries and chafes, we are left with savor.

I no longer seek the elusive unicorn of what’s next, or better, or more exciting around the corner. Bob Marley’s “Every Little Thing Is Gonna Be Alright” is my current theme song. It’s the second day of January. Forget that vague holiday in February and enjoy today. May 2016 unveil your ordinary.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Dec 1, 2015 | Thoughts

My father brought me a cake of suet for Thanksgiving. He’d made it himself, a simple concoction of peanut butter, cornmeal, shortening, and flour. It hangs inside a square wire cage on a pole outside my kitchen window where I watch the birds feast as I wash the dishes.

I learned to take care of the birds from my grandfather, whom I stayed with one summer as a teenager. He took me with him as he strolled around his yard, refilling the various feeders: thistle for the goldfinches, sunflower seeds for the cardinals, jays, and chickadees, and a fruit and mealworm mixture for the woodpeckers and bluebirds. He would patiently mix sugar into warm water for the hummingbirds, and we’d watch them as they flitted and hovered by the sweet juice, their long tongues darting from their needle-like beaks as they drank.

In between doing chores for my grandmother and growing restless after idle hours spent reading, I’d head outside to find my grandfather dozing in the shade, a beer in one hand and a smoldering cigarette in the other. We would while away the afternoon as he taught me to notice the bird songs. I learned to focus and distill one from another, to cut out the background noise of neighbors mowing the lawn and dogs barking down the street. Although I couldn’t always see them, their songs gave them away. The high-pitched chip, chip, chip of the cardinal, the trill of the mockingbirds, the coarse clarion of the blue jays.

In the dusk of the evening, when the light grew too dim to distinguish their colors, he showed me how to recognize each type by its flight pattern, the distinctive swoop and dive of the mockingbird, the short scalloped lift and drop of the cardinal, or the gentle downward flutter of the mourning dove. Once, from the woods that lined the yard’s edge, we heard the muffled staccato hoo-hoo-hoo-HOO of a barn owl and seconds later watched as his shadow fell over the trees and everything in the woods fell silent.

My grandmother’s approach to the birds seemed less philosophical and more focused on portion control. Several trash cans full of seed lined their garage wall, but it was to be doled out only to the colorful songbirds. She hated the greedy purplish black starlings that descended in large flocks and scared away the less aggressive species. She’d sneer in contempt at their shameless effrontery, the feathered one-percenters. Worst of all were the persistent seed-grubbing squirrels. She worked herself into a tizzy, rapping on the kitchen window and yelling at them to scat as they robbed the feeders bare.

A friend of mine once had a brilliant African Gray parrot, which can have the average intelligence of a five-year-old child. Each morning, she’d pull back the shower curtain after her shower and open his cage door, saying, “Are you coming out of there, or what?” One morning, she apparently took a second longer toweling off before opening her curtain, and she heard his impatient voice ask, “Are you coming out of there, or what?” She stowed him under her seat on a flight once, and every time the captain came over the loudspeaker, the parrot would call out, “What?! What?!” causing fellow passengers to cast rude looks at her. The noise and speed of take off excited him so much he yelled at the top of his lungs, “Wowee! Wowee!!” before settling down once they were at cruising altitude, whereupon he sang the entire theme song to Green Acres. He was a rock star.

A bird like that with high intelligence and speech unnerves me; I imagine they must be plotting something. Plus, with the cats that already live here, there would be a constant rehash of all the Sylvester and Tweety episodes ever made, so we consequently never had a caged bird in residence. I am content to enjoy them from a distance, filling my own backyard feeders and setting up houses on fence posts.

Birds are everywhere–city parks, private gardens, forests, wetlands, rooftops, and windowsills. We are essentially surrounded by these wild animals and see them every day, but unless we live in Alaska and own a small dog that would make a delightful morsel for an eagle, we don’t fear them. About as different from us as a species can be, they are untethered to the land, minstrels in the trees, and give birth to eggs. Their bones are hollow and all but weightless, their abdomens are filled with air sacs, and their bodies are coated with soft colorful feathers.

Despite or perhaps because of their differences, birds have been teaching me my whole life. My own backyard is a classroom.

Despite or perhaps because of their differences, birds have been teaching me my whole life. My own backyard is a classroom.

1. Create: Feather your nest. Look around and try to make even the mundane things beautiful. Use horse hair, Easter grass, or Christmas tinsel, but add some sparkle.

2. Have some common sense: My father told us about raising turkeys on their Wisconsin farm. Each year, several would drown because they’d stand out in the rain and look up.

3. Appreciate even small glimpses of beauty: In the woods around my parents’ house, we would often hear the elusive scarlet tanager singing, but it perched so high we rarely saw its blazing color. One of my mother’s greatest delights was spotting that unicorn every now and then.

4. Let loose every once in a while: During a hot, dry summer, after I water the azaleas outside my window, the birds congregate around the puddles and splash with abandon. Dance like no one’s watching.

5. Don’t get in fights you can’t win: Every spring, there’s a persistent cardinal who attacks his own reflection in the side mirror on my husband’s truck. This posturing and bravado goes on for days. The bird in the mirror never backs down.

6. Don’t worry: The sermon on the mount gets to the heart of the matter: look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Who of you by worrying can add a single hour to his life?

7. Soar: Even though we’re grounded earthlings, we can still soar. Look up! Go for it! Take that leap of faith! You have to leave the safety of the nest sometime–it gets crowded in there.

8. Take care of the eggs: Give the littles all they need. Sit on them if necessary. Eventually, they will try their wings and figure out how to fly. (See #6).

9. When the cage door is open, fly: Don’t just sit there in bondage with your shiny mirrors and familiar perch! Are you coming out of there, or what?

by bsquared5@aol.com | Nov 6, 2015 | Thoughts

I am no gymnast; however, being a product of a dyed-in-the-wool Southern girl and a staunch and proper northerner sometimes stretches me into doing the splits across the Mason-Dixon Line.

It’s a scant 3 weeks til Thanksgiving, which reminds me of the strange and serious divide we used to live as kids. After driving over the river and through the woods, whichever grandparents’ house we landed at for the holiday made for an entirely different Thanksgiving.

If we headed north, up to Pennsylvania, the big bird would be full of something called stuffing, kind of a wet and sticky bread concoction that was baked inside the turkey. Getting it inside there called for sticking a hand into the bird’s empty, raw cavity and spooning it in. This is probably how the unfortunate turducken was invented: some squeamish fellow could no longer stomach the stuffing process and sent other lesser birds in one after the other until the turkey could hold no more. The northern table boasted a bowl of cranberry sauce, with round juicy cranberries chunked throughout; long, thin string beans, the French kind, and mashed potatoes and gravy.

If we headed south, to Florida, the bird would be empty, its neck would be boiling in a pot on the stove, and in the oven would be a pan of dressing, made of skillet cornbread, broth from that boiled neck, and dotted with butter. It would emerge golden and crispy on the outside and creamy on the inside, with just the right amount of sage. Cranberry sauce on the southern table would have been a matter of opening a can at both ends and schlopping it onto a plate so it maintained its can shape, which is how cranberries appear in nature. Flat, bacon-flavored green beans would have come from a jar canned from the summer garden’s bounty.

At our house, while the turkey slowly roasted, my mother would steal bits from that boiling turkey neck and eat the gizzards, too, parts my northern kin threw away. No doubt this impulse goes back to that scene in Gone With the Wind, when Scarlett O’Hara rises from the ground, her fist in the air, vowing to never be hungry again. In the South, when your Boogeyman is Sherman and the war of northern aggression, you eat everything.

Then there was grace. At the northern table, we bowed our heads, performed the sign of the cross in unison (all, except my mother), and recited together:

“Bless a Solard, For these Thigh giffs, Which we our battery sieve, From thy bow’d knee, Through Cry Solard, Amen.”

Or at least that’s how it sounded to my childish ears. Eventually, I learned it was more than gibberish: “Bless us, Oh Lord, for these Thy gifts, which we are about to receive, from Thy bounty. Through Christ, our Lord, Amen.”

At the southern table, we didn’t say grace. When my grandfather reached for the biscuits, that was the cue to dig in. Grace was my grandmother’s pride in her cooking, and the hushed quiet that fell over the table as everyone savored each bite. I half wondered, as a kid, if maybe the southern grandmother’s cooking didn’t require as much insurance, coming mostly straight from the garden, which was somehow closer to God than shelved cans from the A&P.

My own little family has now been diluted to only 1/4 northern, and our Thanksgivings are decidedly of the southern ilk. My father-in-law is the official sage tester for the dressing, taking one for the team and facing salmonella every year as he repeatedly tastes the dressing as his wife prepares it, despite the raw eggs. We say a grace that is less recitation and more wandering conversation with our Provider. When my father is there, he listens silently and finishes with his solo sign of the cross, while my decidedly un-Catholic in-laws pretend not to notice so he’s not uncomfortable.

For awhile, after my parents eloped, it was a bit like the Capulet’s and Montague’s. Their union was a convergence of two rivers, the upheaval in the middle sometimes a Bermuda Triangle. It took time for the bristling and resentment to die down. Probably all families are like that, some. We can be contemptuous and jealous, whining petty brats. Three ring circuses of dysfunction.

So when we can sit together without waving flags or firing shots and take a bite of forgiveness or swallow a bit of pride, we say grace to each other. When we can count a few blessings, appreciate who’s no longer there around the table and be grateful for who we’ve still got, even though a little bit of their crazy is showing, grace abounds. They’re silently thinking the same about you (*wink, wink*).

If you can pause for a moment of gratitude before the shoveling ensues, savor it. Savor your abundance of family and food. Laugh out loud in delight if you need to at the patchwork of loopy, messy souls that have your back, some of whom seem to be trying to be hysterical for a living. God bless ’em. Amazing grace.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Oct 25, 2015 | Thoughts

One of my nieces was once so pleased with herself for learning to write her name that she found a rock that fit nicely into her kindergarten-sized hand and scratched out all five letters. Onto the side of my sister’s new van. She even neatly scribbled out one of the letters and corrected it.

After the hell fire and brimstone rained down, she wrote it repeatedly on more appropriate surfaces. Writing, it seemed, was a delightful new skill.

Holding my son’s hand the other day, I realized he was missing something: a writer’s callus. Incredulous, I quizzed his sister and some friends of hers.

“A writer’s what?” they wanted to know.

“You know,” I explained, showing them my right hand, “that bump on the side of your finger where the pen rests. It’s that raised rough spot you get from writing. Like, from taking notes and writing essays.”

The smooth-fingered youths had no idea what I was talking about. My oldest was in third grade a decade ago. That is typically the grade where children are taught cursive writing. That year, they grudgingly made it through about half the alphabet before moving on to another topic. The year after that, the school stopped teaching handwriting altogether. Ask my younger child to sign his name and it’s different each time, a flat squiggled imitation of what he’s observed from his father and me. They write all their work on their laptops and email it in to the teachers. Taking notes in class is sometimes a simple matter of taking a picture of the board with their phones.

I remember spending hours–hours–practicing handwriting on page after page of paper  that looked like miniature roads running from left to right, a dotted center line between two solid lines, the guide for how high each lower-case letter should reach. We were graded on penmanship, required to write our letters to Santa this way, and the requisite post-Christmas thank you notes to far away aunts and uncles. By the time I reached middle school, I could chat with my latest crush and execute countless finely doodled “Mrs. Stephen Bishops**” on the pad by the telephone, wrapped in its spiraled cord. (**Names have been changed to protect said no-good, cheating twerp and my less than stellar character judgement.)

that looked like miniature roads running from left to right, a dotted center line between two solid lines, the guide for how high each lower-case letter should reach. We were graded on penmanship, required to write our letters to Santa this way, and the requisite post-Christmas thank you notes to far away aunts and uncles. By the time I reached middle school, I could chat with my latest crush and execute countless finely doodled “Mrs. Stephen Bishops**” on the pad by the telephone, wrapped in its spiraled cord. (**Names have been changed to protect said no-good, cheating twerp and my less than stellar character judgement.)

When my family moved just before high school, I spent mopey, sulky days writing long letters back “home” to my friends, pages of thoughts, drawings, and stories that grew so bulky the envelopes required reinforcing tape and lots of extra postage. I filled journals, amusing to pull out and read now, my teenage angst leaping from each page, but instructive, now that I am raising teenagers, in remembering what it was like, inhabiting that lonesome territory.

In high school and college, my note-taking was fast and furious, letters small and sure. Small handwriting is supposedly a sign of introversion and an ability to concentrate, in my case probably accurate. Once, for a chemistry test, a teacher cleverly allowed us to bring a “cheat sheet” to class, with a catch: it could only be one inch square. While I am not so focused as to fit entire book chapters on rice grains, like artist Trong G. Nguyen, I managed to fit every chemistry formula I needed on that tiny square. I wrote countless papers and my master’s thesis by hand, typing and retyping it in final draft on an electric typewriter, halfway high on White-Out correction fluid. For graduation gifts, I received several Cross pens, some engraved, which the givers I’m sure imagined would be useful for decades.

I had a meeting the other day with a fellow writer, a guy in his mid-thirties. Curious, I asked if he had a writer’s callus. “No,” he shrugged. “I never even carry a pen.” He quickly transitioned from laptop to ipad to smartphone, typing notes, reading emails, and sending texts. Yesterday’s writer’s callus has morphed into alarming maladies of today: something called “text claw” and thumb arthritis.

Obviously, I have upgraded from my old electric typewriter to a computer. I have a smartphone and I know that an emoji is not a Japanese manga character. Although my teenage son frequently can not believe that I don’t use Siri and the fine points of Apple navigation are lost on me, at least I’m ahead of my father, whose idea of a text message is to send me an email with just the subject line.

Perhaps we have lost something in the rush of progress. I love looking at my husband’s grandfather’s Bible, with his shaky notes written in the margins. I treasure my mother’s handwritten recipes so much that I have one framed on my kitchen counter. At some point, she thought to organize everything and threw most of them away in favor of typed-out note cards. This is why I just cannot, will not, refuse to get on board with the Nooks and Kindles and handheld Bible Apps. Traitorous devices! Electronic highlighting and note taking is not the same as pulling a book from the shelf and happening upon a marginal note I’d written long ago, the handwriting and thinking a reflection of whatever age I was at the time.

A couple of my friends occasionally take the time to write notes. With a pen. On real stationery. It says something more than an email or text. Taking an extra minute to collect a thought or two, commit them to paper, and drop them in an actual mailbox may be a relic from the past, but what a joy to receive it amid the impersonal bills, catalogs, and the usual computer-generated fare. Maybe it’s another one of those genteel Southern graces like handkerchiefs or making a medicinal hot toddy.

I’m afraid someday my grandkids will be texting at Christmas time: Sup, Snta. How ru? Im gud. Pls bring prsnts!

I shudder to think. Until then, I just know I’m mourning the writer’s callus.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Oct 6, 2015 | Thoughts

Waiting in traffic on drawbridges was a fact of life for me as a kid. Unaware of the adult time pressures of schedules and to-do lists, I’d sit in the back of the car watching the stately sailboats gliding like royalty through the raised roadway that halted our progress. Stuck at a standstill, I could get a closer look at the pelicans perched on the watchman’s tower. Once the drawbridge was lowered, I was amazed that we could drive right over a stretch of road that had just a second ago been pointing toward the sky.

Somewhere along the way, that leisurely contentment on bridges gave way to more nervous crossings. I’ve driven over the Golden Gate and Brooklyn Bridges, clomped echoing steps over wooden covered bridges in New England and Madison County, Iowa, hiked across hanging suspension bridges on trails here and there, and cruised over the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers crossing over into neighboring states. There were jaw-dropping views from the Bixby Bridge in Monterey, California, and white-knuckle moments across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge in Maryland. (This bridge is so scary, some people actually pay $50 a day for a service to drive them to work and back!)

Mostly, bridge crossings have been uneventful, but not always. Our car broke down in the middle of the 5-mile long Mackinac Island Bridge in Michigan.

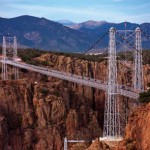

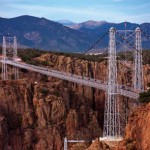

Royal Gorge Bridge

I lost power steering and acceleration and had to coast the last part of the way off the far side. In Colorado, I rode in the back seat hyperventilating as we crossed the Royal Gorge Bridge, the world’s highest suspension bridge, dangling 1,100 feet above the Arkansas River. It was so narrow that passing cars had scant inches between them as they crawled along, and pedestrians walking across had to plaster themselves flat against the railings to avoid being run over. Then there was that one time in a haunted house with my brother where I wet my pants when we crossed a wooden bridge rigged to fall out from under us.

People build bridges, after all–fallible people. Maybe the fact that I hold my breath across them and wince as they sway is more of a flagging trust in human capabilities than an innate fear of bridges themselves. Many of our bridges are aging and need repairs, over 60,000 of them, in fact. So there’s that. The old London-Bridge-is-falling-down nursery rhyme doesn’t really help either. Or those stories about trolls and such living underneath.

Bridges often are the only means to get from here to there, and the truth is, sometimes transitions are just hard. And, oh, goody, life is chock full of these vulnerable, hold-your-breath, learn-to-trust moments. I envy those people who can cartwheel across those bridges with no trepidation. While new and exciting things might wait on the other side, leaving the familiar soil of this side, where my feet are on solid ground and the scenery is just fine, can cause excessive hand wringing.

I have a salt water aquarium in my living room. One night, just after its lights had turned off, I witnessed a hermit crab exchanging its shell for a bigger one. It carefully measured the bigger shell with its antennae. Using its claws to hoist itself up, in one swift move, it hauled itself out of its shell, scuttled across the sand to the new shell, and edged in backwards. Voila! But I was stunned! All we usually see of these crabs is the legs and head, the parts that stick out from under their comfortable shell. When it moved from one shell to the next, its body was revealed. It was a gray comma-like stub, an unformed Voldemort creature. How brave it was to scuttle out from its familiar house, unprotected and exposed!

All of us have our secret underbellies, like the crab, and it’s the worst thing we can think of to crawl out of our comfortable corners and move–grow–into something new. Worse still is to admit to anyone else we might be afraid or unsure of ourselves. Many of us may flinch and wince as we cross bridges of transition—into new careers, empty nests, or life without someone we love. Sometimes, I admit, I cross those bridges trembling on my knees, clinging to the railing and afraid to look down. It helps to have folks around who are no less fearless, but who have made those transitions already. They beckon from the far side, offering encouragement and extending a hand.

Once we make it through our transitions, we can become bridges, of sorts, ourselves. We can span gaps between generations coming along behind and those ahead of us. We can be connectors between old ways of thinking and new. We can extend our hands and assurances that this far side is different, yes, but not so frightening. There are lots of us over here, and we get it.

Twain said that the only person who likes change is a wet baby. Like it or not, change is a constant. Sometimes it demands small alterations, and sometimes it requires of us a full metamorphosis. It’s almost always a surprise and usually terribly inconvenient.

I’m grateful for those who have been on the far sides of my bridges so far. A life that is static and fearful is no life at all. I am learning, slowly, to embrace the change and growth that transitions bring. Sometimes I still squeeze my eyes shut and take hesitant steps, but I have faith that grace will eventually get me where I’m supposed to be. None of us can predict what’s coming down the pike next. But, focusing on the far side, I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it.