by bsquared5@aol.com | Mar 23, 2015 | Thoughts

I’ve been watching the tides at the beach this week, the relentless ebb and flow onto the shelly, sandy shore (say THAT three times, fast). When you’re lazing on the sand, propped up with a book and cold drink, the sea’s rhythm soothes and caresses like a mama with a sick child. There, there, my love, close your eyes and rest and you’ll feel all better soon.

It’s a different story if you’re out beyond the breakers. Despite growing up at the beach, spending a great deal of life in Florida, and having a house with a pool, my mother could not swim. I’m not sure just how she missed out on this life skill, especially given her environment, but there it is. She splashed in the shallows with all of us as children and made sure we could dive and swim with confidence, but she refused to even put her face in the water. She hid it well. I was not even aware of this lapse in her skillset until I was much older. I thought she was joking. “But I’ve seen you in the water,” I said. “You swim.” She shook her head. “I only pretend.”

After I graduated college, my mother and I went on a celebratory cruise, just us. As we island hopped around the Caribbean for several days, we were surrounded by water. She watched from the deck, sipping rum, as I swung off the pirate ship’s rope swing into the clear, blue sea. She watched from the shore while I splashed in the waves on horseback. Towards the end of our trip, we motored out to a small island off the coast of St. Maarten where our group was to spend the afternoon snorkeling over a reef. As the guide handed out fins and masks, he talked about the types of fishes we would see and the areas we should stay in. I was surprised when my mother started putting on the gear.

“I think I can do this,” she said. “It’s not that far off the shore, and I’ll have flippers.” Thrilled, I waded with her into the ocean and we practiced breathing through our snorkels and swimming around where we could still touch. Her face lit up when she spotted the schools of colorful tropical fish darting around the rocks. She pointed them out, gesturing wordlessly as our fins flapped.

The reef we were headed to was not that far, maybe a hundred yards or so. We floated on top of the ocean, bobbing with the waves, parallel to each other as we kicked our fins. It only took about ten minutes before we reached the rocky reef, but by the time we got there, the mood had changed. I noticed she was no longer eagerly searching for bright yellow schools of fish. I raised my head and treaded water, yelling to her where she sat like a nervous mermaid on top of the reef itself, something we weren’t supposed to do. She had yanked off her mask and was breathing hard.

“What? Are you done already?”

Then, for the first time in my life, I realized my mother was afraid. The whole way out we had been swimming against the tide, having to work for every bit of ground gained. The wonder and expectation of the reef had vanished. I had no idea how she’d even gotten on top of the reef at all given its rough surface, but she was there now, clutching the rock desperately. I’d seen her fearful for her children before, especially my brother who seemed to take special delight in racking up ER visits, but never for herself. Until that moment, to me she had been “mom,” the ever-present comforter and provider, who always knew what to do and how to fix it. Suddenly, in a few moments of offshore panic, she had become a person with limitations and fears.

I reasoned with her, the parent-child table turning in disorientation. “We are going to have to get back somehow. You can’t just stay out here.” She didn’t want me to alert the guide and call attention to herself, as if she wasn’t noticeable perched on top of the reef instead of snorkeling around it like everyone else. “I’ll help you,” I said. “You can hold on to me the whole way.” She reluctantly climbed off the rock, put her mask back on and let me swim her back to the shore. When she could touch bottom again, she was angry at herself. The swim back had been much easier, since we’d been going with the tide instead of against it. She admitted it was silly not to have snorkeled around the reef while she was out there. If she’d known it would be so much easier getting back, she wouldn’t have been afraid.

I offered to take her back out but she refused. She waded out and sat on the sand, afraid to try again. It’s one of the moments I remember most from our trip, being startled that my parents were real people in addition to being just my parents. You know, that normal 20’s smack in the head that most of us experience once we’ve outgrown our childish me-centric worldview. I kind of wish I’d had some easing into it, though, because it was truly a shock to my system that affected the remainder of that trip.

Why do parents try so hard to seem infallible to their children? Does it mean we love them more? Can protect them better? Do our words carry more weight? I don’t know any parent who’s played the “I’m perfect” card who is thereby more revered by their children. In fact, it’s mostly just the opposite. When we can be real to our children, confess that we don’t know something, we’ve messed up, we’re imperfect and have character flaws that we’re working on, our kids may just respond with more compassion and forgiveness than we knew they had. Have you ever told your child “I’m sorry, I was wrong”?

We think our children will hold us hostage when we admit truths about ourselves, but the reality is their respect for us grows. If they see us apologizing and working on our faults, it’s more likely they’ll do the same. If we can be humble and ask forgiveness from them, they might surprise us by how bottomless their little compassionate hearts are.

If, when they’re old enough, we can even let them hold us accountable on a thing or two, as an actual real person would with another actual real person, then we’ve really made some strides in the relationship.

I wish I’d fully appreciated my parents earlier. I’d probably have given them a break more, asked different questions, learned different lessons. But, like my mother, I was often content to stick with things the way they were, never imagining what was beneath the surface. I think we both learned something that afternoon. Sometimes the work it takes to swim against the tide rewards you in ways you never would have discovered had you just sat upon the shore.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Mar 10, 2015 | Thoughts

After four girls in a row, in the early 70’s my parents finally had a son, who immediately shook sense into them and put an end to their creation of offspring. This small, blonde, slightly pigeon-toed child gave wet kisses and had trouble saying his “L’s” so he could melt you in seconds with an “I wuv you.”

Despite being adorable, from the time he arrived on the scene, babied and held dear as the sole male child, he was bound and determined to escape and wander free. By the time he was two, he would wake silently in the early morning hours, hop the bars of his crib like a miniature parkour

Houdini in action. Note the padlocked gate: futile.

expert, and head out the front door. My mother’s Spidey Sense would eventually kick in and she’d sit up in alarm, bee-lining for the front yard. He was quick, this little weasel. In no time, he’d have yanked off his sleeper and diapers, leaving them as a trail of breadcrumbs for my poor mother to follow. Somehow, he’d make it across our suburban street into our neighbor’s house across the road. He’d climb onto their kitchen counter and help himself to a couple of cookies from their jar and toddle into their bedroom. Many mornings, they’d wake to the sight of my small brother sitting casually on the end of their bed, naked, his face smeared with chocolate chips. Social services would have had a field day with us.

His unflagging desire to be free–of crib, clothing, and boundaries–made him a walking nightmare for my parents in their house full of kids. We had a backyard pool. As a result, we were one of the first families to enlist Dr. Harvey Barnett, who has since popularized the Infant Swimming Resource (ISR) technique. Before he was walking well, you could throw my brother into the pool and he’d immediately right himself, hold his breath, and paddle to the side to get out. He swam like a fish. Water was apparently his natural and preferred environment. We worried he’d actually start to develop webbing between his toes.

No coincidence, then, that he melded instantly with my mother’s dad, who owned a charter deep sea fishing boat in Panama City. Boat! Water! Fish! Ocean!

At the PCB docks, fish bigger than himself.

My brother’s idea of heaven: sun on your face, wind in your hair, trolling on the open ocean with a fishing pole. While most kids watched Saturday morning cartoons, he preferred hours of National Geographic and Nature, soaking up information about anything marine-related. I could totally see him growing up to replace Aquaman from SuperFriends, riding the backs of dolphins and communicating telepathically with creatures from the deep.

By the time he was in grade school, he could out-fish many grown men. He’d disappear on weekends and head to the nearest canal, coming home at dark smeared with scales and slime, tanned and smiling. I never saw the appeal. I went out once with him and my father and caught a redfish, after I refused to bait the hook with anything that wriggled. He (him, not it) stayed alive in the brackish water in our cooler until we got home. Immediately, I transferred him to our laundry sink, where I monitored him all night for signs of life. The following morning I tearfully demanded my father return him to the river so he could once again be with his friends. I couldn’t bear the thought of a filet knife touching his shiny scales.

My mother tried to keep my brother in sight to corral his wandering. She’d sit him on the counter with her as she cooked

an opah, or moonfish, from Hawaii. It contains 3 different types of meat.

dinner, consulting her red-checked Betty Crocker cookbook. After she died, I’m not sure any of us were surprised when he became a chef, making his way through the industry on his own terms, without boundaries, skipping the expected college route and wrangling an apprenticeship in France. He specialized in seafood. He could spot the freshest specimens and knew which species were in and out of season. His seafood paella is like manna from heaven. As he got older, his skills expanded. He began spear fishing and free diving, holding his breath for over three minutes at depths of 50 feet or so as he scouted the sandy ocean floor for snapper. He got his captain’s license and piloted around the Bahamas, serving as a personal chef for the boat’s owner.

He worked as a chef in Alaska and Miami before his hands gave out from all the slicing and dicing. He’s still in the seafood business, now as a buyer and supplier. And he’s great to have at parties, capable of whipping up tasty morsels at a moment’s notice.

Every time I hear Lee Ann Womack’s song “I Hope You Dance,” I think of my little brother (who is truthfully no longer little and no joke to wrestle with). More than anyone else I know, and probably because he had to realize the “life is short” lesson fairly young in life, he’s done what he loves. And I love that about him.  Career counselors tell people all the time to “do what you love, and the rest will follow.” I love that he’s kept his Houdini spirit intact, taken risks, followed his passions, and thumbed his nose at the expected and the “safe.” It’s made him such an interesting person and inevitably a happier one by using his gifts and talents to make his own path in a career that seems to fall into place tailor made just for him. Not many of us can say the same.

Career counselors tell people all the time to “do what you love, and the rest will follow.” I love that he’s kept his Houdini spirit intact, taken risks, followed his passions, and thumbed his nose at the expected and the “safe.” It’s made him such an interesting person and inevitably a happier one by using his gifts and talents to make his own path in a career that seems to fall into place tailor made just for him. Not many of us can say the same.

He’s got a birthday coming up this week. I hope he gets to spend some time out on the ocean in his kayak, doing what he loves best. Knowing him, that might be wrestling a shark or spearing eels or just paddling across the waves with the taste of salt on his lips. I wuv you, bro.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 23, 2015 | Thoughts

The calendar reminds me it’s time for school pictures this week. I take a deep breath because our family has a bit of a history here. With technology’s advances, photos are as ubiquitous as sunlight or, say, leggings on a college girl. Selfie actually became a real word a couple of years ago in the Oxford English Dictionary. But it wasn’t always so.

When I was in grade school, unless a parent or teacher had a camera in hand, with actual film in it that required developing and processing, we didn’t get many pictures of ourselves, and certainly not ones we could see immediately. School picture day was a big event. We dressed nicely, combed our hair, and tried to smile sweetly.

It would take weeks before our pictures came back, and when they did, it was as exciting as receiving a yearbook in high school. Everyone compared head shots. We carefully snipped the sheets of the 3×2 wallets and exchanged them with each other like baseball trading cards, writing a small note on the back of each one: “To a Good Friend, Stay fun!”

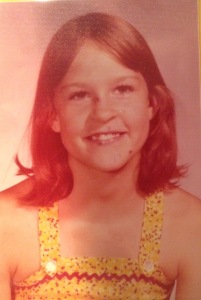

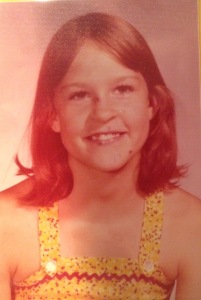

Some of my childhood friends moved to different cities and the last memory I have of  them is their wallet-sized school picture, frozen in 4th grade forever. Inevitably, every school year couldn’t be as cute as that one with the toothless grin in first grade. In fourth grade, I conveniently broke out with a case of cold sores–all over my face. Also, that was the day I wore the flattering bright yellow sundress my mother made me. All my friends who moved away that year have that lovely image to remind them, forever, of me.

them is their wallet-sized school picture, frozen in 4th grade forever. Inevitably, every school year couldn’t be as cute as that one with the toothless grin in first grade. In fourth grade, I conveniently broke out with a case of cold sores–all over my face. Also, that was the day I wore the flattering bright yellow sundress my mother made me. All my friends who moved away that year have that lovely image to remind them, forever, of me.

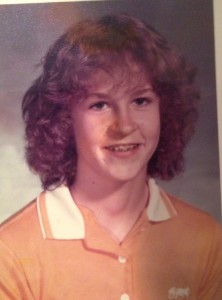

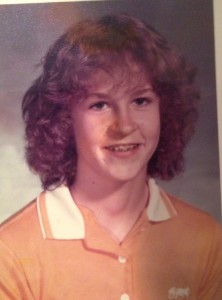

Then there was 7th grade, everyone’s most graceful and poised year of life. Until then, I had fine, straight hair that hung limply around my face. After months of begging my mom for a perm, I got one alright. My rounded Afro frizzed around my head like an electricity experiment gone wrong.  Oh, and that was the year I got braces. Mercifully, I thought to remove the humiliating headgear I had to wear with them before the picture was snapped. Headgear apparently was a leftover of torture from the Middle Ages: a metal bar that wrapped around your face, attached to your back teeth, and harnessed around the back of your neck by a velcro strap. And, again with the mustard yellow color. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that the Color Me Beautiful concept came around and I learned that yellow was not, and never would be, my color. It made me look as if I were just getting over a nasty stomach bug. Seventh grade was not my finest moment.

Oh, and that was the year I got braces. Mercifully, I thought to remove the humiliating headgear I had to wear with them before the picture was snapped. Headgear apparently was a leftover of torture from the Middle Ages: a metal bar that wrapped around your face, attached to your back teeth, and harnessed around the back of your neck by a velcro strap. And, again with the mustard yellow color. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that the Color Me Beautiful concept came around and I learned that yellow was not, and never would be, my color. It made me look as if I were just getting over a nasty stomach bug. Seventh grade was not my finest moment.

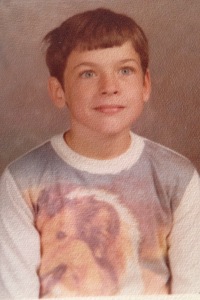

My husband had a classic school picture, too. His was captured in 3rd grade, when he apparently was having a bit of a bad hair day. There’s a note in his childhood scrapbook, written by his mom, that reads, “didn’t think to tell mom we were having pictures made.” That might explain the Lassie shirt and his seemingly stunned expression.

My husband had a classic school picture, too. His was captured in 3rd grade, when he apparently was having a bit of a bad hair day. There’s a note in his childhood scrapbook, written by his mom, that reads, “didn’t think to tell mom we were having pictures made.” That might explain the Lassie shirt and his seemingly stunned expression.

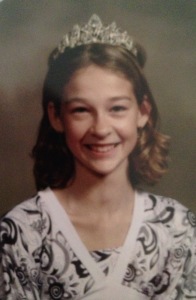

With our sad history of school pictures, I was determined to shepherd my children through the pitfalls of forever having such images represent themselves. When my daughter turned 11, she deemed the day her long-awaited “Golden Birthday.”  No idea where she came up with this, but apparently turning 11 on the 11th is somehow your life’s one magical date. (I guess I missed the significance when I turned 14 on the 14th; no magic for me.) Turns out, her magic day fell on picture day. Imagine my surprise when the pictures finally came back and I realized she’d chosen to immortalize the moment forever by way of a tiara. Future students leafing through the old school yearbooks will not be aware of her reasons and will just imagine she was 6th grade royalty. Perhaps this was her plan all along. Why didn’t I think of that in 7th grade? Then again, the tiara would have been swallowed by my giant hair.

No idea where she came up with this, but apparently turning 11 on the 11th is somehow your life’s one magical date. (I guess I missed the significance when I turned 14 on the 14th; no magic for me.) Turns out, her magic day fell on picture day. Imagine my surprise when the pictures finally came back and I realized she’d chosen to immortalize the moment forever by way of a tiara. Future students leafing through the old school yearbooks will not be aware of her reasons and will just imagine she was 6th grade royalty. Perhaps this was her plan all along. Why didn’t I think of that in 7th grade? Then again, the tiara would have been swallowed by my giant hair.

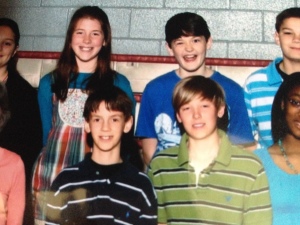

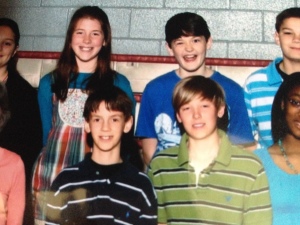

Sadly, my son’s Golden Birthday will not come until he turns 26, long after the school picture opportunity has passed. He has never taken picture day seriously. It has always  been a barrage of reminders to please comb your hair and try a decent smile. In fifth grade, it wasn’t just his own self portrait that he decided to flub. He managed to wait for just the right moment in the class picture to be a goof. Yep, that’s him in the blue shirt looking like Bill the Cat from the Bloom County cartoon. The other parents, when they received this little gem, may have been startled by what appeared to be the child choking in the back row.

been a barrage of reminders to please comb your hair and try a decent smile. In fifth grade, it wasn’t just his own self portrait that he decided to flub. He managed to wait for just the right moment in the class picture to be a goof. Yep, that’s him in the blue shirt looking like Bill the Cat from the Bloom County cartoon. The other parents, when they received this little gem, may have been startled by what appeared to be the child choking in the back row.

I was thinking the other day that, now that homeschooling is on the rise, many students will be able to escape the ignominy of school pictures. And with all the digital technology available, at the very least, they could photo-shop out the weird kid in the back row of a group shot.

Despite the embarrassment at the time, I kind of like having the old school pictures available. I can show my kids that I wasn’t always the specimen of beauty and coolness that they envy today. Everyone is weird. Everyone has been humbled, hated the way they looked, did something dumb, had a period of awkwardness. It’s a universal path that all of us must walk. The edited, filtered, photo-shopped selfies of today are just an illusion. I love Colbie Callait’s song “Try” because she says it’s okay to be real, genuine, messy, and likable anyway.

That’s why, towards the end of my kids’ school years, my favorite pictures have turned out to be the ones where their silliness and fun outweigh their outfits or hair or smiles. It’s why, when I pulled out my 7th grade picture and warned my son to shield his eyes and not look at it directly, we both shared a laugh at just how awful it was. We’re just keepin’ it real, people.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 17, 2015 | Thoughts

Time is marching on and I’m feeling that familiar pressure to forcefully cram lovingly impart all my Wisdom to my son before he’s on his own. A week has gone by and I have made exactly none of the healthy, good-for-you recipes from Pinterest I vowed to try. The bathroom scale mocks me each morning as I step out of the shower. It’s the middle of February and the fragile optimism I held so gently in my hands at the start of the year has started gasping for air as I realize several of my goals for 2015 have yet to see progress.

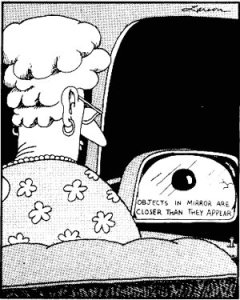

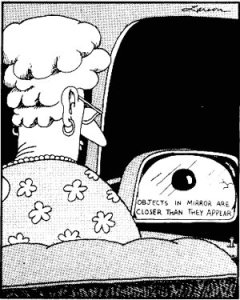

Gary Larson has a classic Far Side cartoon that illustrates how I’m feeling. When I’m focused on meeting all the expectations, trying to keep my eyes on the 16 different balls I’m juggling, all of a sudden there’s a startling eyeball coming up on my right. Objects in mirror are closer than they appear? Yikes!

Gary Larson has a classic Far Side cartoon that illustrates how I’m feeling. When I’m focused on meeting all the expectations, trying to keep my eyes on the 16 different balls I’m juggling, all of a sudden there’s a startling eyeball coming up on my right. Objects in mirror are closer than they appear? Yikes!

When my kids were young, this eyeball was all the stuff I wasn’t doing, catching up to me. The day would start out with such promise and I had so many things I’d want to accomplish, but it could (and usually did) turn on a dime. All my best intentions forgotten, I’d be struggling through the grocery store with frozen food piled on top of my daughter in the basket while my son gummed handfuls of crackers into a soggy mess down the front of his shirt.

Inevitably, some random sweet older woman would give me that look in the checkout line, and I’d think, “Uh-oh, here it comes.”

“Look at your sweet angels. You should treasure each moment, honey. It all goes by in a flash. They’re only like this for the blink of an eye.”

“Really?” I’d think, “because last night when I was changing wet sheets at 2 a.m. it seemed like an eternity.”

The same thing would happen when I was in the middle of the daily exorcism that was my life with a teenage girl. Women who’d been through it with their own offspring would tell me it was just a phase and all but pat me on the head. Oh, a phase? You mean like werewolves go through when they shape-shift? Cool.

What I needed, what I think all moms really need at the core, instead of a wise wink and platitudes that this, too, shall pass and pass quickly, is acknowledgement that what I was doing was hard. The hardest. Physically exhausting, emotionally draining, repetitive, often unrewarded work. I would have preferred a thumbs up, a conspiratorial nod, like they understood that I was doing my best, despite the screaming and tears (from me, not my toddlers or teens).

I was in the mall food court the other day with my teenage son, and it was so crowded we shared half a table with a young mom and her three little ones. The oldest, maybe 4, was up and down after each bite of lunch, kneeling, squirming, and twirling in his seat. It was just a matter of time before he slipped and fell–and I automatically caught him, hands smeared in ketchup, before he hit the ground. His mom was so apologetic. She’d been tending to her baby on her other side when he fell.

“It’s ok,” I said and gestured to my man-child son across from me. She gave me the most grateful look and said, “Yes, so you know. Except he’s big now!” We shared a laugh and I helped her clean up the ketchup all over the table. I didn’t tell her that her kids would not be little like that for long.

Because it’s universal: all moms want is someone to tell us we are doing ok even when it looks like it’s all falling apart. There is no reminder that can guilt her any more than she’s already guilting herself. There is no criticism you can speak that she hasn’t already spoken a hundred times. She’s constantly second-guessing and blundering her way through parenting the best she can, having moments she’s not proud of and moments that she’d never thought she’d be strong enough to endure.

She’ll figure out on her own that the days are long, but the years are short. Those thousand things that seem to be bearing down on you inevitably change into a sense of time passing too quickly.

Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear.

They creep up on you and take your breath in surprise. I look in the rear-view expecting to see my toddler son and suddenly there he is all biceps and big feet, the sweet voice that used to sing Itsy Bitsy Spider now cracking as it strains towards a new sort of bass sound. I call my daughter some days imagining her twirling and skipping and am blown away by her independence and self-assurance.

I used to sing a Hans Christian Andersen song as a lullaby to my children every night.

Inchworm, inchworm,

Measuring the marigolds.

You and your arithmetic will probably go far.

Inchworm, inchworm,

Measuring the marigolds,

Seems to me you’d stop and see how beautiful they are.

(2 and 2 are 4, 4 and 4 are 8, 8 and 8 are 16, 16 and 16 are 32)

It was a good daily reminder, after the grocery stores and the arguing, to stop a minute and really look at my kids, drink them in with all their gifts and strengths and failures and faults.

It was a good daily reminder, after the grocery stores and the arguing, to stop a minute and really look at my kids, drink them in with all their gifts and strengths and failures and faults.

Of course the women were right–we should all treasure the moments. But if we aren’t carpe-ing each diem with zest and glee, it doesn’t mean we have failed. If we stood in awe and amazement during all the moments of every day, we wouldn’t really be honestly living those moments. Instead, we’d be standing around goggling at the beauty and sweetness and letting some important work slide. It’s only in hindsight, no matter how many reminders you get from the well-meaners, that you see the golden field of marigolds you’ve tended.

As Solomon observed, there’s a time and season for everything. A time for tantrums and a time for lullabies, a time for hissy fits and a time for shared confidences. A time for savoring and a time for soldiering, eyeballs and inchworms.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 8, 2015 | Thoughts

Back when my children were toddlers underfoot, there were many days when I heard a constant stream of alternating chatter, screaming, laughing, whining, crying, and singing. Back then, Barney and Dora played incessantly as the soundtrack of my life. I fielded endless “whys” from sunup to sundown. Why I hafta go sleep? Why did Hiccup the hamster die? Why is Dora’s head so big? (That one will have to remain one of the universe’s mysteries.)

Some evenings, after failed attempts at playing “Quiet as a Mouse,” I just had to blurt, “Mommy’s ears are really tired! Can we give them a little rest for a few minutes?” Back then, I would have paid big bucks for five minutes of quiet alone in the bathroom, and nap times were manna from heaven. I mainlined the quiet and stillness like a heroin addict.

Now that one of the children is off to college and the other is completely independent and often doing homework or in his own world wearing headphones at a computer screen, the quiet I longed for has arrived. And it brought along its friends, anxiety and restlessness. The silence prods me: is there something you should be doing? Someone you should be looking after? Where’s that list of To-Do’s and action items?

While I don’t mind the quiet, I’m not very good at it. I come by it honestly. I’m pretty sure I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen my father sit down and just relax. I’m not sure he gets the concept, really. He’ll go on vacation to visit one of his kids and end up patching our drywall, repairing a privacy fence, or installing a ceiling fan. He doesn’t stay in one place for very long. After a couple of days, he’s ready to get back on the road. Things to do, places to go. You know these people. Often they are our mothers or grandmothers, who slaved over holiday feasts only to be bobbing up and down from the table like the Whack-a-Mole game, their own dinners untouched and cold.

A few years ago, I learned of a piece of music composed by John Cage in 1952. It’s called 4’33”, and it consists of three movements entirely of rests. The performer appears on stage, sits at the piano to begin while the audience waits in anticipation, and then nothing. Four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. The pianist counts all the measures of rests as the audience squirms. What is going on? Did he forget the music? Does he have stage fright? People look at one another nervously.

Four minutes and thirty-three seconds is a long time to be quiet. Just ask a toddler playing “Quiet as a Mouse.” Eventually, you start to listen, not to the music, but to the absence of it: the creaking of the seat cushions, a cough, someone’s whisper, the rustle of a program. You’re forced to settle in, get past the initial discomfort, and hear a different sort of music in your surroundings. Even the sound of your own breath becomes a choir of its own, filling the empty air with notes of spontaneous melody.

There is a beauty that arises from stillness, from silence, that we often disregard because it’s not as urgent or demanding as noise. It’s like the well-behaved child reading by herself who gets no attention because the rowdy cousins are swinging from the drapes in the other room. The dearest of friends are those who can sit still with you in the hospital waiting room, those who don’t have to keep up a barrage of chatter lest the room grow uncomfortably quiet. There are tense silences (when you’ve just laid the baby down and are tiptoeing soundlessly out of the nursery like a ninja) and easy, comfortable ones (when you’ve turned in for the night with your spouse and you’re both reading in bed companionably, conversation optional).

What this new-found quiet at my house has taught me is that I haven’t practiced it very much. Silence and I haven’t spent much quality time together. My day is usually full of conversations, phone calls, TV, traffic, the car radio, podcasts, itunes, even a running commentary in my own head, much like those from my kids that used to make my ears so tired. Even if I’m sitting quietly, I’m occupied with a book or my phone.

I know I’m not alone in this. Aside from the technology addiction that many of us have (admitting you have a problem is the first step to recovery, people!), we don’t know how to sit still in the quiet and just be. We demand constant entertainment, distraction, busyness, and noise, which is why the 4’33” concert piece so unnerves audiences. I have to wonder what we are so afraid of? What do we think will fill the quiet if we let it happen? If we turn off the car radio while we’re running errands, what rushes in? If we sit quietly for a few minutes without scrolling through Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or YouTube, what thoughts arise?

Richard Foster’s Celebration of Discipline elaborates on the practice of silence as a spiritual discipline. As with most things spiritual, if you empty yourself of one thing, something else takes its place. Empty yourself of noise and silence settles upon you, often bringing its own kind of disquiet. What thoughts are there, lurking beneath the noise? I’ve been practicing being quiet, enjoying the silence, hearing what’s already there instead of injecting my own noise into the universe.

All the noise is exhausting, and we don’t even realize it until it’s absent and we breathe deeper and our shoulders relax. Without the car radio on, once I run through my own stream of consciousness thoughts, the quiet often leads me to prayer. “Well, I pray,” you say. “I’m so disciplined I even have a quiet time every morning, just me in the quiet before the day starts.” Awesome. You’re way ahead of me. But prayer is a conversation, not just you phoning in your thoughts or requests. Often we just yak away and forget that there’s a second act. Being still and knowing. Listening in the quiet. If you don’t think that there might be an answer, then why waste your time in prayer? No telling what might bubble up from the quiet and surprise you. The still, small voice is awfully hard to hear when you drown it out.

In the movie Get Smart, one of the coolest gadgets was the Cone of Silence. Once under it,  all noise completely stopped, like inside a vacuum. Being a silence rookie, I wish I had one of these convenient devices that I could activate whenever I need a “moment of silence.” (There I go, dependent on technology again.)

all noise completely stopped, like inside a vacuum. Being a silence rookie, I wish I had one of these convenient devices that I could activate whenever I need a “moment of silence.” (There I go, dependent on technology again.)

I still appreciate some noise in my days. I like a good car jam as well as anyone (celebration is also a spiritual discipline, by the way)! But I’m learning through my circumstances and newly quiet house to appreciate the silence and the lessons it teaches.