by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 5, 2015 | Thoughts

These cold February days have me day dreaming about my Floridian childhood. Most of my formative years were spent on Florida’s Space Coast, the stomping ground of Major Nelson and Jeannie from the 1970’s I Dream of Jeannie show.

We lived just a few blocks from the ocean, although we rarely went. Hard to believe now that we actually schedule family vacations for that very purpose, but familiarity breeds contempt, I suppose. Our beach was rocky and full of seaweed and many times was a minefield full of clumps of sticky tar that was impossible to scrub from your feet. Still, we would sometimes be lucky enough to spot a loggerhead turtle laying her eggs, scooping sand with her flippers to cover the nest before heading back out to sea.

Our zip code designated our address as Satellite Beach, about an hour south of Orlando and central Florida’s tourist Mecca. We had Florida resident and military discounts to Disney and Sea World, so I lost count of how many times we were there. Once I got older, my friends and I got dropped off at the gate a few times by our parents, kind of like the mall hangout for today’s crowd, except instead of Hollister and the Cookie Store, we got Mickey and Shamu. Space Mountain’s roller coaster in the dark was our version of living on the edge.

The Magic Kingdom wasn’t the only magical aspect of my childhood. Where the Indian and Banana Rivers converged in south Merritt Island,

dragon point, “Annie”; from Florida Today

there was a huge mansion at the island’s tip. There used to be a 20-ton statue of a dragon (named Annie) that jutted out into the water, as if she were scooping up minnows from the shallows. Every time we passed that dragon, I’d dream up stories about her life and what she did there. I heard just recently that the mansion is being repaired and the dragon restored–hurray!

We had no seasons: shorts and flip flops at Christmas, shorter shorts and bare feet in the summer. Palm trees stayed the same all year. The only way you knew the holidays were approaching was the change in inventory at the stores. The first winter after moving away, my freshman English teacher stopped class to let me go outside in the snow that was drifting down. I’d never seen snow that I remembered, and she thought it was high time. Summer must be over because school would start up again, and people wouldn’t run the sprinklers in their yards as often. This was a good thing since we were constantly outside sprinting through our neighbors’ yards, and you never knew when their timers would be set to come on, soaking you with smelly sulfur water in the middle of a good game of tag.

Periodically, NASA would announce a rocket launch, and we’d hurry through dinner so we could sit on the picnic table in the backyard and watch it light up the sky, a vertical plume of flame and smoke trailing from its tail as it sped towards its orbit. For really important ones, we’d head to the beach and sit on the sand, listening in the dark for the familiar bass rumble. It was better than a fireworks show. On their way back from Japan after I was born, my parents had watched on the airport TV screens as the Apollo 11 astronauts took their first steps on the moon. About 13 years later, one afternoon when I was in gym class, we looked up to see the Shuttle Columbia and its escort jets flying home to Kennedy Space Center after its recent landing in California. It flew so low I could make out the windows on its side, and we all cheered and waved.

In January of my senior year, I was in Tennessee home from school for a snow day watching TV as the Challenger exploded in mid-launch. We felt it personally, having watched it launch several times from our backyard. One of my sisters worked at Cape Canaveral, where the loss was traumatic and the effects were felt for years afterward.

When we weren’t peering up at the night sky, we were running barefoot in the sunshine. For a time, my family had a boat that we’d take out onto the Indian River. We’d motor under the drawbridges and through the canals, winding our way to the many islands that dotted the river’s landscape. I loved to putter alongside a gently floating school of manatees, their gray backs breaching the surface like ancient whales. Occasionally we’d hand-feed them heads of iceberg lettuce, their whiskery faces peering at us while they munched.

my brother & me, an afternoon on the water

We would anchor at one of these outcroppings and pile out with the day’s lunch and our portable grill. We learned how to dig in the wet sand at the water’s edge with our toes, finding clams that we’d toss on the grill until they popped open, revealing their salty, slightly gritty meat.

I learned to love seafood. My grandfather owned a charter deep sea fishing boat in Panama City, and we’d regularly stock up on fresh-caught grouper and snapper. My parents would go out at night with friends and throw nets from the bridges, hauling in all-you-could-eat shrimp. My dad had a tour of duty assignment in the Grand Turk islands, and he would bring back coolers of conch and lobster, packed on ice. It wasn’t until I was much older that I realized, sadly, that lobster wasn’t an every-day menu item.

One of my friends had a small two-man sailboat. We were not yet old enough for a driver’s license, but she could pilot the little craft around the canals, through the watery backyards of the neighborhood. That was all the freedom we needed, sans wheels.

My father was anxious to leave. Being raised in Wisconsin and Maryland, he couldn’t stand the summer heat. He constantly muttered about the cars, our bikes, and his tools rusting because of the salt air from the ocean breeze. We had to time our exits from the house so as to open the door the minimum amount of time possible, edging through in the briefest of seconds or else he’d yell, “Shut the door!” Obviously we were trying to air condition the entire neighborhood! We were also not allowed to turn on the oven for this reason. The a/c ran constantly, turning him into a miser who constantly monitored the thermostat. But kids don’t see the adult reasoning behind all that frustration. My Florida was an oasis of warmth and ocean breezes, punctuated by the occasional hurricane. We rode our bikes for miles over the flat terrain: to and from school, the library, the movies, friends’ houses. It was a freer time then, before kids were monitored every second through scheduled play dates and after-school activities. We had to be back to our neighborhood before the street lights came on and close enough to hear my father’s whistle for dinner time.

Three of my siblings still call Florida home, so I can easily visit. I have the best of both worlds, with the occasional snowfall and hardwood trees that turn glorious in the fall here and a means to answer the Siren’s call of the ocean whenever I feel the pull. Like, for example, on gray February days like these.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 29, 2015 | Thoughts

In the spring of 2013, the KKK held a rally in Memphis protesting the renaming of some parks named for Confederate notables. This lingering blight of racism is one of the few things I dislike about where I live, but fortunately I usually only encounter it in small pockets of my state.

Although I heard ugly remarks from my grandparent’s generation, my parents didn’t raise us that way. In South Carolina we lived on a diverse military base, and my sisters would bring friends by the house, some of them black. My brother was maybe 3 or 4 at the time, and he was fascinated by the difference. He toddled over, repeatedly rubbing the arm of one of their friends once, bewildered. “Why he dirty?” he asked my sister, thinking if he just rubbed hard enough the black would come off. The boy thought it was hilarious, despite my sisters’ embarrassment.

I suppose because of this sort of thing, we talked about differences a lot, and I learned early about equality and race. My mother hailed from rural Alabama during the 40’s and 50’s and had formed some firm ideas about how people should be treated. She was ahead of her time on that issue. I often heard her talk passionately about civil rights, feminism, and WWII’s holocaust. People are people, she used to say. She didn’t cotton to some older ways of thinking. As a result, my hackles always rise when I hear an off-color remark, and I can get pretty heated over stereotypes.

Which is why my husband, son, and father-in-law were astounded to see my van parked on the edge of a secret KKK meeting close to our neighborhood. It was the same weekend as the Memphis rally, and the boys had just driven by a wooded area where white-hooded figures were circled in the woods just off the road. Alarmed, Bob turned his truck around, ready to come rescue me because he just knew I’d gone storming into their midst with righteous indignation, and he imagined my horrible fate. Just as they were about to pull into the field, it dawned on him. That morning I was attending a beekeeping class, and we had gone into the field to get some hands-on hive experience. Beekeepers wear white suits and white hats with veils. We were circled around a hive, watching our instructor install a new queen into a hive in the woods. I wasn’t even aware the heroic trio had been there until I walked into the house after the class and they burst out laughing, relaying their mistake.

There’s a great chapter on race in Bronson & Merryman’s book Nurture Shock (2009) that surprised me. White parents tend to think that by not pointing out differences and making general statements like “everybody’s equal,” or “God made everyone” we are raising color blind children. Young children have an innate developmental need to categorize everything to make sense of the world. If you haven’t specifically pointed out differences and explained them, they will create their own divisions–“those like me” and “those not like me.” Think about how we talk about gender (mommies can be doctors and firefighters just like daddies), but we are often silent about race unless we are forced into it by explaining an international adoption or interracial marriage. To a child, our silence on the matter leaves them to identify with (and prefer) those most like him. What this means is that racism is not necessarily taught. It’s an inference that’s made from an early age (way before 3rd grade) because no one mentioned and corrected it.

In minority families, race is discussed more, but it’s often in the context of preparing a child to face discrimination. Sadly, some of this talk is still necessary in our culture. But too much of it tends to be as negative as actual experiences of discrimination. Instead of connecting their success to effort, children who hear this sort of thing frequently tend to blame their failures on others because they see others as biased against them.

A few years ago, we spent some time with friends in Tanzania, Africa. It was a disorienting reversal of culture, as we became the racial minority. We were pointed at in the market, people saying, “Mzungu!” (Swahili for “white person”). Small children were often afraid of us. They’d never seen a white person before and thought we were ghosts. In these areas, children born with albinism (pale or white skin) were often attacked, their limbs severed for witch-doctor practices. This was fear of the “other” at its most basic level.

We were most definitely “not like them.” At least on the surface. Once the children saw their images on an iPhone camera, their curiosity overcame fear. It was pure joy watching my son and a small boy interact, swapping hats and laughing at each other in the shared language of play. People in the village wondered at our skin, our different hair, and especially the braces on my son’s teeth. Once I sat on the dirt floor of the hut with the other women, sifting rocks out of the rice that was to be our lunch, color became irrelevant as we all shared the communal work of women the world over–feeding our families and watching over the children–not so different after all.

Another village invited us to share in a worship service in their community church. Although the entire thing was conducted in Swahili and Sukuma, we followed along easily with the spirited singing and prayers. Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight, Jesus loves the little children of the world. The simple children’s song echoed in my head with the beauty of our fellowship.

one of these things is not like the others…

Not so different after all.

I find all the research about race fascinating, especially in light of the racially charged controversy between police and minority communities that’s played out all over the media in the past year. Obviously a remote village in Africa is not equivalent to the streets of American cities. Even so, if we took the time to see each other with different eyes, to recognize our common humanity, surely we would walk a few steps further towards one another and away from our fearful “not like me” instincts.

You don’t need to travel across the globe to teach your children that people are people. Certainly a key way to make a difference and affect change is to start talking–early and specifically–to our young children. They need to know that we are aware of differences and that it’s okay to talk about them. Just like gender, it’s only surface stuff. Underneath, we all want the same things and have the same feelings.

Not every hooded person is sinister.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 25, 2015 | Thoughts

A couple of years ago we took a trip to New York City. We got a great guide book, marked off the tourist spots we wanted to see, made some reservations, and set off, intrepid travelers full of expectation. And expectations were met. After JFK spewed us from its terminal, we held on for dear life in a dirty yellow taxi clearly driven by a madman.

Sweating and breathless, I gasped at the near misses and close calls with cars and bicycles as we weaved our way to our hotel. As much as possible, I craned my neck this way and that, trying like a sponge to absorb the city view. Apartments running from block to block, laundry hung from the railings and fire escapes; lines of uniformed children on their way to a field trip at the museum on the corner; bricks, asphalt, concrete; shop windows full of women’s clothing, street carts offering a quick tasty lunch; glassed-in buildings stretching tall, so high you couldn’t see the tops without tipping your head back and back until dizziness set in. So much to see!

One of my best childhood friends works in a building in Times Square. Once we left our hotel and made our way to her office, we stood in the middle of the block, turning like rotisseries, goggling at the lights, colors, costumed performers, and advertisements, each boasting more movement and neon than the last. It was exhausting, the definition of sensory overload.

We entered her building and it was as if we’d stepped into an alternate universe. The vacuous lobby echoed with the clack of polished heels. Overhead lights reflected on the chrome and glass in muted shades of gray and sophisticated ivory. I felt myself relax from the absence of sensory onslaught. My friend was dismissive of the display just outside the doors. She waved her hand and rolled her eyes. “This is just for the tourists,” she said. “If you live here, it’s kind of embarrassing.” She gave us pointers on what to see for the afternoon and suggested we download KickMap, a great app for navigating the subway. “Also,” she said, “Use Maps on your phone for when you come up out of the stations. It can be disorienting.”

Duly armed, we made our way to the nearest station and set off for our first tourist site. We must have walked miles that day, jostling with other pedestrians: all nationalities and colors, crowds of tourists, students from NYU, women in business suits and tennis shoes, hoofing to their next destination, high heels stowed in their designer bags. Up and down into the subway stations we went, going from the gusty winds and sirens above to the stuffy, graffiti-ed tunnels below. Every time–EVERY time–I emerged from the steps onto the street, pushed by the flow of people, my neck swiveled like a dizzy owl as I tried to get my bearings. Which street was this? Which direction were we headed? I’d consult the Maps app on my phone, watch the blinking beacon that was “me” as I walked, and nine times out of ten I’d be headed the wrong way.

the wrong way.

Admittedly, a sense of direction was not one of my gifts. When I was a kid, the compass rose on the top of a map caused me no end of confusion. North was always at the top, so I reasoned that it was always in front of me. Whichever direction I faced as I held the map, no matter where I was standing, would always be North. East was always to my right, South always behind. My disoriented brain did not comprehend that the directions were constant, while I was the one changing. At dinner parties, my father would call me over and ask which direction I was facing. “North,” I would say, exasperated, “Always North!” (Ok, so I was never in Girl Scouts.)

At the end of our sight-seeing day, we came up out of a subway station and a woman kept pushing my shoulder from behind, saying “Excuse me.” I kept edging out of her way, but she kept pushing until I began to feel nervous and hug my purse tighter. When I finally turned my head to give her a “back off, lady” look, I realized why she persisted. She was blind. She was in her mid 60’s, short with frizzy brown hair, and had a heavy New York accent. She clearly expected me to do her bidding. I turned to her, and as she sensed my posture change, she hooked her arm in mine. “Can you point me in the direction of East 125th?”

I was already fumbling with the apps on my phone. I stammered, “I’m not actually from here.” She had no patience with my incompetence. “I know where I’m going,” she huffed, “Just point me in the direction. I don’t know how this subway comes up.” By some miraculous stroke of luck, I happened to spot a street sign that was where she wanted to go. I took a couple steps in that direction and told her that was the way. She unhooked her cane from her free arm and set off confidently, her face tilted slightly up and to the left, as if she were listening to a pleasant melody.

I stood there stunned, my destination forgotten. All I could think was how confused I’d been all day, the distances I’d traveled, the sights I’d seen, the swirl of color and lights in Times Square. How I could barely navigate my way a few blocks with the repeated use of maps and constant landmark checking. You know that game where you’re blindfolded and spun around and then asked to hit the hanging pinata? She lived that every day. Except instead of whacking a paper donkey for candy she was making her way through the congested streets of one of the biggest cities in the world.

She amazed and humbled me, this stranger, in our brief encounter. While my husband and kids stood huddled over their phones, debating over which way we should head, I leaned back against the rough brick of a corner building and shut my eyes. I imagined the life the woman might lead, and tried to distinguish direction without any visual cues. The city’s sensory attack was definitely thwarted without sight. With the sirens, honking taxis, cell phone conversations, and footsteps, I couldn’t discern any helpful pattern. Smells: hot dogs, sewage, someone’s bold choice of cologne, exhaust fumes. Opening my eyes in panic, I realized how brave she was, not even a service dog to help guide her.

During the rest of our stay, I noticed the streets differently. I marked the neighborhoods not by sight but tried to distinguish them by sound or smell. The perfume of the flower stall on the corner, the spicy Thai restaurant, the quiet conversation of the old men playing chess by NYU, a solo saxophonist making music under a bridge in Central Park. It was a game, eavesdropping on the city, trying to decipher the clues of my surroundings. I let the family navigate by sight as I trailed along fascinated by the city’s other senses.

How ironic that a blind woman would have added such depth to my sight-seeing. I still can’t find my way out of a paper bag. But when we travel now, I frequently pause to appreciate the non-visual aspects of a new place, to think how I would describe it to someone without sight. That day, we were each an example of the blind leading the blind. I’d thought I was taking in the city in all its glory, but she showed me a deeper way to “sight see.”

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 24, 2015 | Thoughts

When you live where we do, you get used to hearing tornado warnings on TV, usually in the spring. I’ve lost count of how many tornadoes have swept through our area with the accompanying hail storms, wind damage, and insurance claims. The weather man’s refrain is stuck in my head like an 80’s song. “Find your safe place. Go to an interior room with no windows. Cover your head.” For now, that place is our closet, where many times we have crammed in beneath the hanging pants with our sleepy children and uncooperative pets in the middle of the night.

Some friends of ours relocated here from out west, and they recounted their reaction the first time they heard the unfamiliar urgent warnings. As they should, they took it seriously and huddled in the bathtub together, hunkering down. “Cover your head,” the weather man said, so they earnestly scrambled to follow directions. They ended up making their children wear bike helmets while they each donned 5-gallon buckets from Home Depot. I always chuckle when I remember their story, imagining the newspaper photos and puzzled looks from the authorities if their house had been swept away and they’d been found that way, staggering out from the wreckage topped with buckets.

In the movie Unbroken, depicting the incredible life of Louis Zamperini, there’s a scene where he and two other men from his unit are stranded on a life raft in the middle of the ocean. As they’re floating along with the sharks, figuring their odds of survival are slim, one of his buddies says to Louis, “I’m glad it was you.” If your plane is going down and you’re faced with many lean days in the middle of nowhere, you hope you’re paired with someone decent, level-headed, and strong.

I think of myself as a realist, which is why when it comes to relationships I tend to discard Nicholas Sparks and other sappy fodder. In my experience, real life tends to be more like Louis’ lifeboat or the tornado closet. Don’t get me wrong. I believe in butterflies and a twinkle in the eye. Even, perhaps, in love at first sight. But pheromones and weak knees aren’t going to get you through the storms. And as anyone who’s been married more than a couple of years can tell you, butterflies have a short life span.

I always thought the traditional marriage vows should be more specific. Maybe if they were, fewer people would actually marry for superficial reasons. Instead of:

I, (name), take you (name), to be my (wife/husband), to have and to hold from this day forward, for better or for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish; from this day forward until death do us part,

How about:

I, (name), take you (name), to be my (wife/husband), to have and to hold from this day forward, through infertility, miscarriages, and the loss of a child; through late nights worrying about a sick baby or a wayward young adult; through special needs and learning disabilities; through bankruptcy and job loss; through bad investments and mounting debt; through annoying habits, hair loss, and weight gain; through scary diagnoses, surgery, and recovery; through loss of grandparents, parents, and others; through bad decisions and character flaws; through dementia and cancer, stubbornness and selfishness. I pledge to love and cherish you, to be faithful to you no matter what, and to hold you up when you’re weak, scared, or too tired to go on. Forever and ever, Amen.

In the movies, they say, “You’re not the person I thought you were.” They say, “You’ve become someone else.” They say, “I’ve fallen out of love with you.” Unless they’re stuck in the ridiculous body of a 100-year-old sparkly vampire, of course the person you marry will change. Don’t you hope they will? If you’re not different at 50 than you were at 20, then you are stagnating. If life, loss, and parenthood doesn’t change you, then you’re more of a statue than a human being. Newsflash: real marriage is not like the movies. It doesn’t wrap up after an intense star-gazing courtship and end happily at the altar while the credits roll. That’s just the start. You’re fresh off the assembly line and have just hit the road. Once the warranty runs out, you can expect the new smell to wear thin and a couple of dings to appear on the bumpers. That doesn’t mean it’s all a big mistake or you’ve missed your destiny. It may just mean that you’re doing it right.

Gold, like that ring on your left hand, is a soft metal. It bends. It is easily hammered, forged, changed.

Long-lived, married love is not the butterflies, although they’re there in the distance. It’s often brilliant and easy, comfortable and true. It’s a choice you make every day to stay. To be faithful, to make an effort, to be available, to help each other grow. It’s something you cobble together, every day, day after day, by choice and sometimes by sheer force of will as you grit your teeth and bear down. And if you do that, over and over, day after day, then sometimes, in moments that may startle you, the butterflies revisit. They alight when you see your husband patiently helping with math homework or when he fills the car up with gas, when your wife rocks and sings to the baby, when you see him decked out in a great suit, or when she’s curled up asleep on the pillows. If all you’re after is a constant stream of giggles and stolen kisses, then you’re a string of affairs waiting to happen.

You can’t always predict the way a person will react to disappointment or tragedy. But watch the way they handle a traffic jam, plans that changed at the last minute, lost keys, or a phone call to Comcast. Witness their response to someone else’s sadness or bad news. Is there compassion? Patience? Empathy? Even-temperedness? If necessary, would you want to be in a lifeboat with them? If you heard the weatherman say “Hunker down, folks and find your safe place,” would it be with them?

Sometimes when we’re dating we may be so busy star-gazing and dreaming about the warm, sandy beach honeymoon and the picnics with flowers and wine, that we forget about the likelihood of hurricanes. And sometimes, despite our best efforts, we can be blindsided by a tsunami that devastates everything in its path and leaves us clinging to a tree for dear life. Sadly, some storms, with some people, just cannot be survived.

After being married only a few years, I once said to a group of women that your husband (spouse) kind of has to love you, they’re like family. A woman I’d just met corrected me sharply. “Oh, no, they don’t,” she said. “You were born into your family. Your spouse has a choice to make.” Her husband had recently left her. Take away lesson: for better or for worse, but never, never for granted.

At the end of our wedding ceremony, my husband and I walked down the aisle to “When I’m 64” by the Beatles. Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64? We have quite a few more years before we hit that mark, but so far I’ve always been able to look over and say, “I’m glad it’s you” when the high winds have started to howl. Sometimes we may look silly stumbling along with buckets on our heads, but I’m grateful that we are each other’s safe place.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 14, 2015 | Thoughts

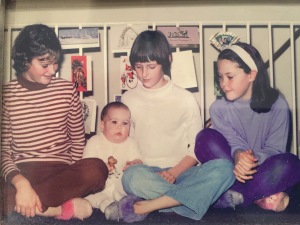

I am a fourth-born and a first-born. My parents had this great little family of 3 daughters, each two years apart. Then they waited 8 years and had me and my younger brother in quick succession. Though this technically ranks me fourth, the large gap made us kind of a split-level family, and I got the typical first-born personality while resting firmly in the middle of the pack.

This also meant that my older sisters had two different parents than my brother and I. Oh, they were the same mom and dad, but my sisters had them when they were young and fresh. My brother and I, as usual, got hand-me-downs. Parents worn out and frayed from years of use, whose eyes were not as vigilant, and whose determination to teach us certain skills was lagging. The older three always accuse my brother and me of having some sort of fantasy childhoods, with no supervision or required chores (but they’re not at all bitter).

Their tales of responsibilities and chores could be true. My “hand-me-down father” used to make me spend hours hand-trimming the St. Augustine grass under the chain-link in the backyard because the fence supposedly damaged the weed-eater’s trimmer line. I suspect this was less of a fact and more of an excuse to get me outside and building character. If this was an example of his lighter, more relaxed task-doling, then maybe they really were triple Cinderellas.

In my sisters’ childhoods, before my brother arrived as the family’s caboose, my father taught all three of them to play softball. My grandmother (his mom) scolded him, terrified he pitched way too fast. He argued that if he didn’t pitch fast and hard, they wouldn’t be motivated to catch the ball. When your options were to either catch it or get beaned by a 50 mph fast ball, you quickly developed good hand-eye coordination. All three of them played on girls’ softball leagues and could hit, field, and run like Geena Davis in A League of Their Own.

By the time I was old enough to have a go, the gloves were already broken in and soft. All but one sister had flown the nest, and either my father’s interest had waned or, more likely, a decade or more had passed and he was just more tired. He had already taught the sport three times and maybe he had run out of gumption to do it once more. I never caught a blazing softball and, as a result, was one of those picked last in junior high gym. In fact, I never played any team sport, and while my brother did, he didn’t stick with any of them for long. We each ended up preferring more solitary activities: him, fishing; me, riding horses.

My hand-me-down parents may have been worn out from repeatedly raising toddlers and teens, but they were also wiser. In his fascinating book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell explains how the magic number of becoming an expert at something is 10,000 hours of practice. If you go by the numbers, after just one year (8,760 hours) of parenting, you’re already almost a success. The catch, and there’s always a catch, is that right about the time you’re an expert on babies, they become toddlers and you’re back at ground zero. Then they hit kindergarten and everything changes. Dump some hormones and puberty in the mix, and just when you thought you were making progress, you go straight to jail, do not pass Go. Becoming an expert in parenting (if there even is such a thing) takes twenty times longer than any other skill because the target keeps moving. (Gladwell has no children, by the way.) Because they had so many of us, my parents had gone through these phases multiple times and were experts 10 times over by the time my brother and I arrived on the scene. Raising two more kids was like buttah.

If we didn’t change and grow as we age, if we parented all our children making the same rookie mistakes we made on our first-born darlings, it would be weird. I hope I’m not the same parent in my 40’s as I was in my 20’s! This morphing parent phenomenon is most obvious when your own parents become grandparents. Our jaws have dropped on more than one occasion when our parents have allowed our kids to do things that would have earned us a well-tanned hide. Remember the Abraham & Isaac story? Faithful Abraham dutifully prepared to sacrifice his teenage son. Show me the altar, he said. (They’d probably just been arguing about too much texting or getting the car keys to go the mall.) I’ve often said that if Isaac had been Abraham’s grandson, Abraham would have scooped him up and run like the wind, and Genesis would read very differently.

My husband and I discuss this in wonder. Who are these people? They are not the same people who raised us. And if they’re doing it right they shouldn’t be. The Skin Horse in the classic Velveteen Rabbit story explains how being loved by a child makes you more Real: “It doesn’t happen all at once. You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby.”

I appreciate my sisters blazing the trail with our parents. They got the handmade clothes, bad bangs, and strict curfews. It’s a mixed bag, though. The hand-me-down parents I got may have been more relaxed and financially better off, but no matter what my brother and I threw at them, it wasn’t their first rodeo, and they fielded our fastballs with ease. As younger siblings we did have the benefit of watching and learning from everybody else’s experiences. From my sisters we learned not to let dad catch you sit ting around watching TV when he got home from work, and the best time to ask mom for permission for something was when she was almost asleep in her chair.

ting around watching TV when he got home from work, and the best time to ask mom for permission for something was when she was almost asleep in her chair.

When we compare childhood experiences, we marvel at how different they are. It’s not like they were in a gulag and we were raised by wolves, but to hear them tell it, well, almost. Thanks for limbering them up for us, guys. Way to take one for the team!

the wrong way.

the wrong way.

ting around watching TV when he got home from work, and the best time to ask mom for permission for something was when she was almost asleep in her chair.

ting around watching TV when he got home from work, and the best time to ask mom for permission for something was when she was almost asleep in her chair.