by bsquared5@aol.com | Apr 15, 2015 | Thoughts

I learned exactly zero domestic skills from my mother. It wasn’t due to her lack of trying to impart them. With a needle and thread, she crafted quilts, clothing, and toys. With a few things from the pantry, she whipped up deliciousness nightly. She could fold towels and fitted sheets with military precision. Early on, I gave up on the sewing; I hadn’t the patience. My “folded” fitted sheets still look like wrinkled irregular lumps in an otherwise neat stack of linens.

When I was a little older and had realized that it wasn’t just the magical Kitchen Elves who created the wonderful smells wafting into the living room where I sat, usually with my nose in a book, I did start to show some curiosity about how to make things besides pop tarts and cold cereal.

The problem was my mother was taught by her mother, a quintessential Southern cook. When we’d visit my grandparents in Panama City, Mammaw would be bustling around in her frozen-in-the-1950’s-kitchen, making huge quantities of cheese grits, from-scratch biscuits with special “Mammaw butter” enhanced with buttermilk, and mounds of light and fluffy scrambled eggs. Her cobblers were legendary, her fried chicken a lost art in this era of kale and protein smoothies.

I’d hover around the oven like a bee drawn by honey, waiting for those flaky biscuits to emerge. Once or twice, when I got bored of climbing the trees in the yard or trapping blue crabs with my brother, she tried to show me how it was done. Something about flour, milk, and salt, but I don’t remember the rest. I tried to write it down. Wait. How much milk again? “Oh, you know, about this much.” Well, how much is that? A tablespoon? “Just til it looks right.” How do I know when it looks right? “Just add it until it’s the right consistency.” She was getting frustrated, stirring with more vigor than necessary. I gave up, content to just observe from afar.

My mother was the same way. I’d call her and ask for a particular recipe for one of my favorites. That special lasagna sauce? Well, you have to add a little sugar. Right. How much is a little? Which one of the measuring spoons in my drawer do I use for that? Heavy sigh over the phone. You just have to taste it to know.

No written directions! Chaos! Culinary anarchy! Who could cook anything with this insanity? Somehow, you’re just supposed to know how to go rogue with the cookie recipe printed on the Tollhouse packaging. I know it says to add one cup (2 sticks) of butter, but really you should use only one stick and half a cup of shortening. What? Why? My Type-A orderly brain would go into panic mode when given these types of suggestions.

And then there was cole slaw. If you’re from the South, you’ve got to have a go-to cole slaw recipe for family gatherings and summer cookouts. My mother had one. Hers was the only cole slaw I would ever eat for many years. After she died, I lost the taste of cole slaw right along with her. No one else’s could ever equal it; they were always too vinegar-y or too mayonnaise-y.

Some years ago, I was lolly-gagging (as my dad would say) at a yard sale and stumbled upon what looked like a medieval torture device. But I knew it for what it really was: an exact replica of my mother’s cole slaw shredder. Eureka! It was a steel tripod with a hand crank with interchangeable barrels for different grating settings. You’d push a wedge of cabbage or carrot through the top while turning the crank and perfect shreds would come out the barrel right into my great grandmother’s green Homer Laughlin orange blossom bowl. I already had the bowl. My mother had painstakingly scoured antique stores for several of them to be sure each of us had at least one. No kitchen was complete without a “Grandmother Bonnie bowl.” She died before ebay was a thing; she could have done some serious damage with ebay.

Some years ago, I was lolly-gagging (as my dad would say) at a yard sale and stumbled upon what looked like a medieval torture device. But I knew it for what it really was: an exact replica of my mother’s cole slaw shredder. Eureka! It was a steel tripod with a hand crank with interchangeable barrels for different grating settings. You’d push a wedge of cabbage or carrot through the top while turning the crank and perfect shreds would come out the barrel right into my great grandmother’s green Homer Laughlin orange blossom bowl. I already had the bowl. My mother had painstakingly scoured antique stores for several of them to be sure each of us had at least one. No kitchen was complete without a “Grandmother Bonnie bowl.” She died before ebay was a thing; she could have done some serious damage with ebay.

Now, now after all these years I could make mom’s cole slaw and recreate that childhood pleasure! On the way home from the yard sale, I stopped at the grocery store for  cabbage and carrots. Having happily shredded both into the obligatory green bowl, I called one of my sisters for the next step. “I’m making mom’s cole slaw,” I said, perhaps a tad manic in my excitement. “What do I do after I’ve shredded everything?” You have to add dill pickle juice. “Great!” I said, grabbing a jar with one hand and wedging the phone between my shoulder and ear. “I’ve got some right here! How much?”

cabbage and carrots. Having happily shredded both into the obligatory green bowl, I called one of my sisters for the next step. “I’m making mom’s cole slaw,” I said, perhaps a tad manic in my excitement. “What do I do after I’ve shredded everything?” You have to add dill pickle juice. “Great!” I said, grabbing a jar with one hand and wedging the phone between my shoulder and ear. “I’ve got some right here! How much?”

“Oh, y’know, til it tastes right.” Seriously? I felt like Charlie Brown having fallen for the football gag…again. I finished making it, but it wasn’t exactly how I remembered. I put the grating contraption up on the topmost shelf of my pantry, where it sits in shame gathering dust to this day. I had such great hopes for it.

I will sometimes grudgingly eat cole slaw now, but every bite is a disappointment. I limp along with my version of the lasagna sauce. Every batch of my chocolate chip cookies is always made with half butter, half shortening, although I still do not know why.

I ain’t no Rachel Ray or Martha Stewart by any stretch. But I’ve begun to get the “consistency” thing in other areas. I hear people talk about trying to achieve balance in their lives, between work and family and all the rest. News stories are popping up about “free range” parenting versus the prevalent “helicopter” type. We struggle with purposeful self-improvement and spiritual depth versus binge watching Netflix for an entire weekend.

How do you know when you’ve got it right? What do the media, the magazine quizzes, the current gurus say? For me, it’s a matter of intuition. A little of this, a little of that, not too much of any one thing. It’s not a matter of the exact right bowl or accessory. Taste frequently and when you’ve reached the right consistency, you’ll know. More of those “ahh” moments of joy will pop up–with your spouse, your kids, your work. Formulas and recipes, even for left-brained personalities like mine, usually aren’t the way true masterpieces are made.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Apr 4, 2015 | Thoughts

It’s time for more chocolate. Valentine’s Day has begun to blur in distant memory, and Christmas stocking loot has long since been picked over. With the long span of desolation before Halloween’s bounty, enter The Easter Basket. Jelly beans, Peeps, plastic eggs filled with various delights, and the giant chocolate rabbit towering over it all—that should last at least a week.

dressed up for Easter Sunday

Easter Sundays when I was a kid were made for dressing up and going to church. We didn’t go so far as the traditional bonnets, but I remember the pinchy patent-leather shoes and starchy stiff dresses that I wore while squirming in the pew, heady with the incense the white-robed priest waved through the aisles. Easter mass always ran longer than regular Sundays. After weeks of Lenten fish-on-Fridays, I was eager to get home for the Basket of Joy, but it always seemed God&Jesus had other plans.

We had your basic straw baskets with a long handle. 364 days a year they lived on top of the china hutch in the dining room. When we woke up Easter morning and they were no longer in their lofty perch, we couldn’t wait to find them. The bunny, that human-sized, Santa-like creature, would hide our baskets and we’d have to search to see what he’d left us. One very disappointing year, the big chocolate bunny was white chocolate–which is no chocolate at all, in my opinion. I tried to trade with my brother, but he was no fool. That year my bunny sat unwrapped, its strange blue candy eyes staring out from the cellophane. I would never free him. White chocolate, indeed.

How to eat that large bunny was a puzzle. Did you bite his ears off first, so he couldn’t hear? Maybe a foot so he could no longer hop? His stub of a tail seemed the most innocuous place to start. The end was inevitable, but at least you could ease him into the idea. I had a rampant imagination as a child, and every year consuming the rabbit was agonizing. But he was chocolate, after all, and it was as unavoidable as Easter mass.

my sister, Terri, hunting eggs in what appears to be tennis shoes and a spring-ish ladies’ nightie.

After lunch, we’d hunt for eggs that my father would hide in the yard. Days before, my mother had mixed up a concoction of vinegar and food coloring, and we’d eagerly dyed the hard-boiled eggs, dunking them repeatedly in every color until they were not so much the happy pastel colors she intended as they were a murky earthy brown. Better for my father to hide them that way; they blended in with the bushes. Even my older sisters, usually too cool for such things, would participate. After that, I was done with the eggs. They’d been handled and hunted, cracked and smushed, left under shrubs to be found in the heat of a Floridian afternoon. I would never actually eat them. Plus, there aren’t many things nastier than hard-boiled eggs. Except maybe white chocolate.

I’d go to bed that night having eaten more candy than was wise, and throughout the week, I’d get to take some to school in my lunchbox to prolong the sweetness. By the following Sunday, there wasn’t much left in the basket other than mismatched plastic eggs and a tangled mess of Easter grass that had moist jelly beans stuck in it. Eventually my father would get sick of yelling at us to pick up the Easter grass that got trailed all over the house and the baskets would retire back up to the penthouse on the china hutch for another year.

Ben can’t smile big enough–he’s so happy to see the bunny

I don’t remember ever actually visiting the Easter Bunny, but for awhile, with my own children, we made the annual pilgrimage to the mall to see the cotton-tailed giant himself. Strangely, they were not afraid of him, despite the fact that no real rabbit they’d ever seen had vacant unblinking eyes or stood six feet tall. Unlike with Santa, they never sat in his lap screaming in terror. Children usually have one of three responses to large characters like this: (1) sheer, primeval terror; (2) desperate, maniacal love; or (3) a strange violent urge to whale on the poor creature like the padded-suit guy in self-defense classes. Thankfully, my children were in the second classification and we never had startling bunny encounters at the mall.

The Bunny visited our house much the same way he did when I was a child. The kids would always have to find their hidden baskets somewhere around the house on Easter morning. They picked through the colored straw grass to find the treasures hidden inside, and then we’d head to church to reflect on why we even had Easter baskets in the first place. It was about love, not candy. In the afternoon, we’d hunt eggs all through the yard–plastic eggs, no smelly hard-boiled ones at my house.

For many years we hosted a party for our friends and their children. We would  round up baby bunnies or chicks for them to hold and pet. Once we borrowed a lamb for the event, which we had to bottle feed every few hours throughout the night. Why? Because baby animals! After a group meal, we’d line up all the kids to unleash them on the yard for a massive egg hunt. Watching the youngest toddle around carefully picking up an egg here and there was so sweet. The older ones ran pell-mell through the yard in full-on competition mode. Afterwards, there was always a grand exchange of favorite candy and faces smeared in chocolate.

round up baby bunnies or chicks for them to hold and pet. Once we borrowed a lamb for the event, which we had to bottle feed every few hours throughout the night. Why? Because baby animals! After a group meal, we’d line up all the kids to unleash them on the yard for a massive egg hunt. Watching the youngest toddle around carefully picking up an egg here and there was so sweet. The older ones ran pell-mell through the yard in full-on competition mode. Afterwards, there was always a grand exchange of favorite candy and faces smeared in chocolate.

You can debate the merits of Peeps and jelly beans all day, but the faith, family and friends that are the focus of Easter are what make it one of my favorite holidays. As long as there’s no white chocolate. 😉

by bsquared5@aol.com | Mar 31, 2015 | Thoughts

Lots of people I know like to go to the beach but won’t get in the ocean. Things with teeth live there where you can’t see them, they say. Or things that sting or pinch. The undertow, the waves, the rocks beneath the breakers. All true.

I was in the ocean in North Florida with my brother one time when he scooped up a harmless clump of floating seaweed and proceeded to shake it. Out came a handful of living creatures that had been hitching a ride—tiny crabs, translucent shrimp, and unnamed life that quickly swam away. I was stunned and a bit startled. Who knew?

There’s a lot out there in the vast blue camouflaged as simple ocean. One of my sisters used to collect beach glass, storing it for some unknown purpose in jars in her bedroom. The misty shards of green, blue, and brown had been tumbled, tossed, and polished by the sea for who knows how long before her long fingers plucked them from the sand where they’d washed up amid the crush of shells.

Every year in the world’s oceans thousands of accidental container spills occur from rogue waves or storms that hit cargo ships. As a result, beachcombers have run across some odd items that have washed ashore: thousands of bags of Doritos, Nike shoes, unripe bananas, rubber ducks. Not to mention the unique and haunting debris that is still washing up on beaches from the tsunami that swept over Japan in 2011.

These things, like the living villages of seaweed, are out there just following the currents, sometimes for years, before they’re deposited on a stretch of sand somewhere. I’m fascinated by movies about people drifting at sea like Unbroken, Life of Pi, or Castaway. Out there on the infinity of ocean, wouldn’t it be surreal to feel your trailing hand bump something in the water only to find that it’s a drifting flock of hundreds of yellow rubber ducks?

I’ve been trying to take a more positive outlook lately and focus on the gifts that arrive at my shore unbidden instead of the things I suspect are lurking under the waves. Children are always good teachers in this respect. For them, everything is a gift, a joy to be explored. Even the weird purple jellyfish quivering at the water’s edge or the battered driftwood and crushed shells (these make lovely sand castle decorations).

Yes, there are Things With Teeth out there. But there are also starfish and sand dollars and bioluminescent plankton that sets the sea aglow at night. It’s so easy, habit, instinct to focus on the shelf of rocks under the waves, the undertow that some days seems to relentlessly drag me under. But then fear wins.

This year I’m determined not to let fear win. It’s such a niggling little parasite, sucking the joy and life from the best moments, and it doesn’t deserve my attention. Especially when, look, there are so many gifts, if I’d just see, washing up on shore to be treasured.

At the beach this week, I watch these small children play and laugh. They chase the seagulls because no one has told them they can’t be caught. They built castle after castle in the sand because no one has told them they will be washed away by morning, and the joy was in the building anyway, not the permanence. They shriek and dance, running from the cold waves onto the safety of shore, but before the day is out, they will always, always be waist-deep in the water, no longer afraid of the rush or crash. When did I decide I would give in to fear? Was there a single moment, a mark-able before and after? More likely a long, steady neglect of the tide’s treasures and a gradual habit of tired defeatism.

Many of us carry around the weight of fear like a slimy fish freshly caught, slapping against our legs as we walk, causing our steps to falter. Fear of letting go. Fear of opening your heart to love. Fear of doing that thing you’ve always wanted to do. Fear of stepping out in faith. Fear of forgiving someone and losing the kernel of resentment and anger you’ve held onto. The reasonable thing to do would be to toss that fish on the bank and leave it lying, flopping and gasping for air. Because we’ve carried it so long and so faithfully, it somehow seems cruel to cast it aside.

Finding Nemo is one of my favorite movies. There’s a scene where, in their search for his son, Marlin and Dory are stuck inside a whale. The water is going down and, as far as they know, they are in danger of being swallowed. Dory tells Marlin to let go. It seems like the right thing to do. Marlin, fearful from the start of the movie, screams, “How do you know something bad won’t happen?” Dory replies simply, “I don’t,” and then she lets go and slides down the whale’s gullet.

We are never guaranteed freedom from bad things, things with teeth. But if we never let go, if we never toss aside that slimy fish, we are most definitely guaranteed freedom from discovery, joy, and the treasures that wash ashore.

Thanks for reading! To return to the FICTION WRITERS BLOG HOP on Julie Valerie’s website, click Here

by bsquared5@aol.com | Mar 26, 2015 | Thoughts

For Mother’s Day several years ago my family gave me a manure spreader–because nothing screams “mom” like a device for waste management. Despite probably having some deep subliminal meaning that I chose to ignore, it was actually exactly what I had asked for. The fact that I now had actual manure to spread meant only one thing: I had a horse.

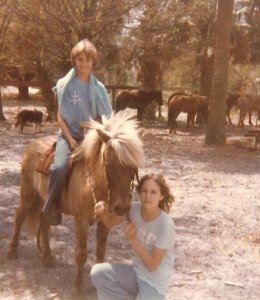

When I was nine I begged my parents to enroll me in a “basics of horsemanship” class at

Corky, the sneaky pond pony

our community Rec Center. Each weekend during the summer, we carpooled out to a seedy little horse farm with patchwork fencing and stalls cobbled together from spare lumber where I learned how to ride shaggy ponies in a Western saddle. A small murky pond sat in the middle of the main pasture (more sand than grass) where we’d have our lessons. Many times, Corky, the temperamental Shetland I rode, decided the lesson was over and took an abrupt right turn straight into the pond. I’d balance atop the saddle, my legs held high to keep dry, pulling at his bridle and mane in futile desperation to get back on dry land.

Eventually that horse farm folded, and my parents thought that was the end of my foray into horses. Silly parents! My friend Linda and I soon moved on to grander pastures. We started spending weekends at an English riding stable run by a one-armed German named August Gruen. He’d sit astride his Thoroughbred chestnut stallion and clear six foot fences as if they were nothing, all this while holding shortened reins with his one hand.

Technically, we were “working students,” which meant we traded labor on the farm for riding lessons. In reality, each weekend, we sweated profusely in the Florida sun mucking stalls, shoveling sand, pitching hay, creosoting fences, lugging sloshy water buckets, and cleaning and oiling leather tack. By the time our fathers arrived to shuttle us back home, were were covered in sweat and filth and sometimes smelled so bad they’d drive all the way home with the windows down. Utter bliss.

All through my childhood, my every waking thought was consumed by what I’d do at the horse farm that weekend. I learned classical dressage, cross-country, and stadium jumping. Every extra penny I had went into riding gear and model Breyer horses. On the days we weren’t at the farm, we’d play with the models, imagining we were rich horse trainers, stables full. Either that or we’d pretend to be horses ourselves, setting up “jump courses” in the yard with chairs and broomsticks, trotting and tossing our heads as we cleared the rails.

A canal ran through the farm, ending in a large pond of dark water. Happily, by this time, I’d figured out how to prevent ponies from darting there as a throw-me-off tactic. Instead, after a morning of cleaning stalls, we’d hop bareback onto the horses and ride them into the pond on purpose. The moment when the horse beneath you reaches a depth where it loses solid footing and starts to swim is magical. As I held on to the wet mane and gripped with my knees to keep from sliding off, it felt a bit like flying, weightless, the horse’s nose angled above the water as it snorted and whuffed, enjoying the coolness.

It was Florida, after all, and there were known gators somewhere in the waterway. We could hear them croaking to each other like mammoth bullfrogs at dusk. Occasionally, we’d find headless turtles left on the banks, a small snack left abandoned. Either the bravado of our youth or the muscular pumping of the horse’s legs were enough to ward off the beasts while we swam. We were flippant and fearless as long as we were tethered to the horses.

All my significant injuries have been from horses: cracked rib from falling off during a jump over a water obstacle, broken wrist when the saddle slid off at a gallop (my fault for not checking the girth), sliding face first on a gravel driveway beneath galloping hooves, and a purple and yellow bruise the size of a grapefruit on my hip from being bitten by a particularly bad-tempered Tennessee Walking Horse (why I’ve never cared for the breed since).

When we moved from Florida and my Mecca horse childhood, I mourned. My only solace was that my parents had bought acreage in Tennessee, which meant pasture and room for a horse. I had a solid “maybe” from my parents, so I reluctantly boarded the moving van. I had only three years at home before heading off to college at that point, so rather than dive into the money pit, my father stalled until the timing of buying a horse became impractical. This is perhaps the one thing I have trouble forgiving him for.

Years later, in my late 30’s, we finally landed in a spot with pasture and (gasp) a ready-made barn. Once again, the scent of pine shavings and hay filled my days. I spent long stretches of time with a curry comb and hoof pick, stocked up on carrots and remembered how to clean and oil a bridle, even briefly showing again at a hunter-jumper event. These days, the ground seems a lot harder than it did when I was 12, and I’m not as quick to take chances with a half-ton animal. But I sure enjoy looking out the window and seeing a horse in the field, calmly grazing and swishing the flies with his tail.

Growing up with horses gave me a grand sense of power, freedom, motion, and imagination that formed who I would become as an adult. When most girls my age were obsessed with lip gloss and slumber parties, I was laboring in the sun and dirt, kissing that Barbie-doll female image goodbye. If I fell off, my German instructor gave me a withering “Stop crying and get back on that horse!” and I learned how to correct my mistake so it wouldn’t happen again. I learned the boundaries of taking risks, earning respect of a being that had a will, copped attitude, and could crush me if it chose (much like a two-year old, now that I think about it!).

Horses grant a deep connection. You’re balanced atop an animal capable of running over 50 mph, and all you do is turn your head to the right and give a slight pressure of your right calf, and magically, intuitively, your mount changes direction beneath you. A light touch of the rein and his head bows in an arc, ears swiveling as he waits for your next cue. It’s ballet. It’s orchestral harmony. A video of Stacy Westfall from several years ago never fails to give me chills:

https://youtu.be/TKK7AXLOUNo .

Carrots and sugar cubes are not enough reward for this gift. I’ve lost two horses over time and my mourning for them ran deep.

I’ve had to take a double-dose of Advil for the past two days after spending several hours spring cleaning stalls. But I’d rather have that than an empty pasture. I’ll take my manure spreader over a tennis bracelet any day.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Mar 23, 2015 | Thoughts

I’ve been watching the tides at the beach this week, the relentless ebb and flow onto the shelly, sandy shore (say THAT three times, fast). When you’re lazing on the sand, propped up with a book and cold drink, the sea’s rhythm soothes and caresses like a mama with a sick child. There, there, my love, close your eyes and rest and you’ll feel all better soon.

It’s a different story if you’re out beyond the breakers. Despite growing up at the beach, spending a great deal of life in Florida, and having a house with a pool, my mother could not swim. I’m not sure just how she missed out on this life skill, especially given her environment, but there it is. She splashed in the shallows with all of us as children and made sure we could dive and swim with confidence, but she refused to even put her face in the water. She hid it well. I was not even aware of this lapse in her skillset until I was much older. I thought she was joking. “But I’ve seen you in the water,” I said. “You swim.” She shook her head. “I only pretend.”

After I graduated college, my mother and I went on a celebratory cruise, just us. As we island hopped around the Caribbean for several days, we were surrounded by water. She watched from the deck, sipping rum, as I swung off the pirate ship’s rope swing into the clear, blue sea. She watched from the shore while I splashed in the waves on horseback. Towards the end of our trip, we motored out to a small island off the coast of St. Maarten where our group was to spend the afternoon snorkeling over a reef. As the guide handed out fins and masks, he talked about the types of fishes we would see and the areas we should stay in. I was surprised when my mother started putting on the gear.

“I think I can do this,” she said. “It’s not that far off the shore, and I’ll have flippers.” Thrilled, I waded with her into the ocean and we practiced breathing through our snorkels and swimming around where we could still touch. Her face lit up when she spotted the schools of colorful tropical fish darting around the rocks. She pointed them out, gesturing wordlessly as our fins flapped.

The reef we were headed to was not that far, maybe a hundred yards or so. We floated on top of the ocean, bobbing with the waves, parallel to each other as we kicked our fins. It only took about ten minutes before we reached the rocky reef, but by the time we got there, the mood had changed. I noticed she was no longer eagerly searching for bright yellow schools of fish. I raised my head and treaded water, yelling to her where she sat like a nervous mermaid on top of the reef itself, something we weren’t supposed to do. She had yanked off her mask and was breathing hard.

“What? Are you done already?”

Then, for the first time in my life, I realized my mother was afraid. The whole way out we had been swimming against the tide, having to work for every bit of ground gained. The wonder and expectation of the reef had vanished. I had no idea how she’d even gotten on top of the reef at all given its rough surface, but she was there now, clutching the rock desperately. I’d seen her fearful for her children before, especially my brother who seemed to take special delight in racking up ER visits, but never for herself. Until that moment, to me she had been “mom,” the ever-present comforter and provider, who always knew what to do and how to fix it. Suddenly, in a few moments of offshore panic, she had become a person with limitations and fears.

I reasoned with her, the parent-child table turning in disorientation. “We are going to have to get back somehow. You can’t just stay out here.” She didn’t want me to alert the guide and call attention to herself, as if she wasn’t noticeable perched on top of the reef instead of snorkeling around it like everyone else. “I’ll help you,” I said. “You can hold on to me the whole way.” She reluctantly climbed off the rock, put her mask back on and let me swim her back to the shore. When she could touch bottom again, she was angry at herself. The swim back had been much easier, since we’d been going with the tide instead of against it. She admitted it was silly not to have snorkeled around the reef while she was out there. If she’d known it would be so much easier getting back, she wouldn’t have been afraid.

I offered to take her back out but she refused. She waded out and sat on the sand, afraid to try again. It’s one of the moments I remember most from our trip, being startled that my parents were real people in addition to being just my parents. You know, that normal 20’s smack in the head that most of us experience once we’ve outgrown our childish me-centric worldview. I kind of wish I’d had some easing into it, though, because it was truly a shock to my system that affected the remainder of that trip.

Why do parents try so hard to seem infallible to their children? Does it mean we love them more? Can protect them better? Do our words carry more weight? I don’t know any parent who’s played the “I’m perfect” card who is thereby more revered by their children. In fact, it’s mostly just the opposite. When we can be real to our children, confess that we don’t know something, we’ve messed up, we’re imperfect and have character flaws that we’re working on, our kids may just respond with more compassion and forgiveness than we knew they had. Have you ever told your child “I’m sorry, I was wrong”?

We think our children will hold us hostage when we admit truths about ourselves, but the reality is their respect for us grows. If they see us apologizing and working on our faults, it’s more likely they’ll do the same. If we can be humble and ask forgiveness from them, they might surprise us by how bottomless their little compassionate hearts are.

If, when they’re old enough, we can even let them hold us accountable on a thing or two, as an actual real person would with another actual real person, then we’ve really made some strides in the relationship.

I wish I’d fully appreciated my parents earlier. I’d probably have given them a break more, asked different questions, learned different lessons. But, like my mother, I was often content to stick with things the way they were, never imagining what was beneath the surface. I think we both learned something that afternoon. Sometimes the work it takes to swim against the tide rewards you in ways you never would have discovered had you just sat upon the shore.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Mar 10, 2015 | Thoughts

After four girls in a row, in the early 70’s my parents finally had a son, who immediately shook sense into them and put an end to their creation of offspring. This small, blonde, slightly pigeon-toed child gave wet kisses and had trouble saying his “L’s” so he could melt you in seconds with an “I wuv you.”

Despite being adorable, from the time he arrived on the scene, babied and held dear as the sole male child, he was bound and determined to escape and wander free. By the time he was two, he would wake silently in the early morning hours, hop the bars of his crib like a miniature parkour

Houdini in action. Note the padlocked gate: futile.

expert, and head out the front door. My mother’s Spidey Sense would eventually kick in and she’d sit up in alarm, bee-lining for the front yard. He was quick, this little weasel. In no time, he’d have yanked off his sleeper and diapers, leaving them as a trail of breadcrumbs for my poor mother to follow. Somehow, he’d make it across our suburban street into our neighbor’s house across the road. He’d climb onto their kitchen counter and help himself to a couple of cookies from their jar and toddle into their bedroom. Many mornings, they’d wake to the sight of my small brother sitting casually on the end of their bed, naked, his face smeared with chocolate chips. Social services would have had a field day with us.

His unflagging desire to be free–of crib, clothing, and boundaries–made him a walking nightmare for my parents in their house full of kids. We had a backyard pool. As a result, we were one of the first families to enlist Dr. Harvey Barnett, who has since popularized the Infant Swimming Resource (ISR) technique. Before he was walking well, you could throw my brother into the pool and he’d immediately right himself, hold his breath, and paddle to the side to get out. He swam like a fish. Water was apparently his natural and preferred environment. We worried he’d actually start to develop webbing between his toes.

No coincidence, then, that he melded instantly with my mother’s dad, who owned a charter deep sea fishing boat in Panama City. Boat! Water! Fish! Ocean!

At the PCB docks, fish bigger than himself.

My brother’s idea of heaven: sun on your face, wind in your hair, trolling on the open ocean with a fishing pole. While most kids watched Saturday morning cartoons, he preferred hours of National Geographic and Nature, soaking up information about anything marine-related. I could totally see him growing up to replace Aquaman from SuperFriends, riding the backs of dolphins and communicating telepathically with creatures from the deep.

By the time he was in grade school, he could out-fish many grown men. He’d disappear on weekends and head to the nearest canal, coming home at dark smeared with scales and slime, tanned and smiling. I never saw the appeal. I went out once with him and my father and caught a redfish, after I refused to bait the hook with anything that wriggled. He (him, not it) stayed alive in the brackish water in our cooler until we got home. Immediately, I transferred him to our laundry sink, where I monitored him all night for signs of life. The following morning I tearfully demanded my father return him to the river so he could once again be with his friends. I couldn’t bear the thought of a filet knife touching his shiny scales.

My mother tried to keep my brother in sight to corral his wandering. She’d sit him on the counter with her as she cooked

an opah, or moonfish, from Hawaii. It contains 3 different types of meat.

dinner, consulting her red-checked Betty Crocker cookbook. After she died, I’m not sure any of us were surprised when he became a chef, making his way through the industry on his own terms, without boundaries, skipping the expected college route and wrangling an apprenticeship in France. He specialized in seafood. He could spot the freshest specimens and knew which species were in and out of season. His seafood paella is like manna from heaven. As he got older, his skills expanded. He began spear fishing and free diving, holding his breath for over three minutes at depths of 50 feet or so as he scouted the sandy ocean floor for snapper. He got his captain’s license and piloted around the Bahamas, serving as a personal chef for the boat’s owner.

He worked as a chef in Alaska and Miami before his hands gave out from all the slicing and dicing. He’s still in the seafood business, now as a buyer and supplier. And he’s great to have at parties, capable of whipping up tasty morsels at a moment’s notice.

Every time I hear Lee Ann Womack’s song “I Hope You Dance,” I think of my little brother (who is truthfully no longer little and no joke to wrestle with). More than anyone else I know, and probably because he had to realize the “life is short” lesson fairly young in life, he’s done what he loves. And I love that about him.  Career counselors tell people all the time to “do what you love, and the rest will follow.” I love that he’s kept his Houdini spirit intact, taken risks, followed his passions, and thumbed his nose at the expected and the “safe.” It’s made him such an interesting person and inevitably a happier one by using his gifts and talents to make his own path in a career that seems to fall into place tailor made just for him. Not many of us can say the same.

Career counselors tell people all the time to “do what you love, and the rest will follow.” I love that he’s kept his Houdini spirit intact, taken risks, followed his passions, and thumbed his nose at the expected and the “safe.” It’s made him such an interesting person and inevitably a happier one by using his gifts and talents to make his own path in a career that seems to fall into place tailor made just for him. Not many of us can say the same.

He’s got a birthday coming up this week. I hope he gets to spend some time out on the ocean in his kayak, doing what he loves best. Knowing him, that might be wrestling a shark or spearing eels or just paddling across the waves with the taste of salt on his lips. I wuv you, bro.

Some years ago, I was lolly-gagging (as my dad would say) at a yard sale and stumbled upon what looked like a medieval torture device. But I knew it for what it really was: an exact replica of my mother’s cole slaw shredder. Eureka! It was a steel tripod with a hand crank with interchangeable barrels for different grating settings. You’d push a wedge of cabbage or carrot through the top while turning the crank and perfect shreds would come out the barrel right into my great grandmother’s green Homer Laughlin orange blossom bowl. I already had the bowl. My mother had painstakingly scoured antique stores for several of them to be sure each of us had at least one. No kitchen was complete without a “Grandmother Bonnie bowl.” She died before ebay was a thing; she could have done some serious damage with ebay.

Some years ago, I was lolly-gagging (as my dad would say) at a yard sale and stumbled upon what looked like a medieval torture device. But I knew it for what it really was: an exact replica of my mother’s cole slaw shredder. Eureka! It was a steel tripod with a hand crank with interchangeable barrels for different grating settings. You’d push a wedge of cabbage or carrot through the top while turning the crank and perfect shreds would come out the barrel right into my great grandmother’s green Homer Laughlin orange blossom bowl. I already had the bowl. My mother had painstakingly scoured antique stores for several of them to be sure each of us had at least one. No kitchen was complete without a “Grandmother Bonnie bowl.” She died before ebay was a thing; she could have done some serious damage with ebay. cabbage and carrots. Having happily shredded both into the obligatory green bowl, I called one of my sisters for the next step. “I’m making mom’s cole slaw,” I said, perhaps a tad manic in my excitement. “What do I do after I’ve shredded everything?” You have to add dill pickle juice. “Great!” I said, grabbing a jar with one hand and wedging the phone between my shoulder and ear. “I’ve got some right here! How much?”

cabbage and carrots. Having happily shredded both into the obligatory green bowl, I called one of my sisters for the next step. “I’m making mom’s cole slaw,” I said, perhaps a tad manic in my excitement. “What do I do after I’ve shredded everything?” You have to add dill pickle juice. “Great!” I said, grabbing a jar with one hand and wedging the phone between my shoulder and ear. “I’ve got some right here! How much?”