by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 23, 2015 | Thoughts

The calendar reminds me it’s time for school pictures this week. I take a deep breath because our family has a bit of a history here. With technology’s advances, photos are as ubiquitous as sunlight or, say, leggings on a college girl. Selfie actually became a real word a couple of years ago in the Oxford English Dictionary. But it wasn’t always so.

When I was in grade school, unless a parent or teacher had a camera in hand, with actual film in it that required developing and processing, we didn’t get many pictures of ourselves, and certainly not ones we could see immediately. School picture day was a big event. We dressed nicely, combed our hair, and tried to smile sweetly.

It would take weeks before our pictures came back, and when they did, it was as exciting as receiving a yearbook in high school. Everyone compared head shots. We carefully snipped the sheets of the 3×2 wallets and exchanged them with each other like baseball trading cards, writing a small note on the back of each one: “To a Good Friend, Stay fun!”

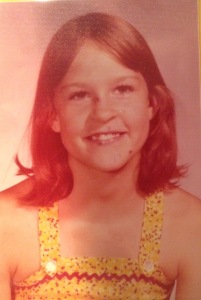

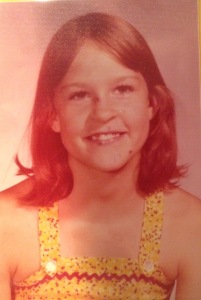

Some of my childhood friends moved to different cities and the last memory I have of  them is their wallet-sized school picture, frozen in 4th grade forever. Inevitably, every school year couldn’t be as cute as that one with the toothless grin in first grade. In fourth grade, I conveniently broke out with a case of cold sores–all over my face. Also, that was the day I wore the flattering bright yellow sundress my mother made me. All my friends who moved away that year have that lovely image to remind them, forever, of me.

them is their wallet-sized school picture, frozen in 4th grade forever. Inevitably, every school year couldn’t be as cute as that one with the toothless grin in first grade. In fourth grade, I conveniently broke out with a case of cold sores–all over my face. Also, that was the day I wore the flattering bright yellow sundress my mother made me. All my friends who moved away that year have that lovely image to remind them, forever, of me.

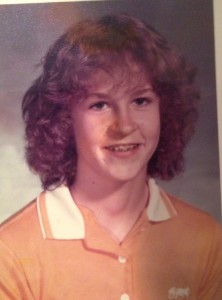

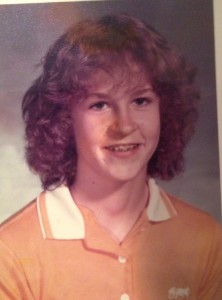

Then there was 7th grade, everyone’s most graceful and poised year of life. Until then, I had fine, straight hair that hung limply around my face. After months of begging my mom for a perm, I got one alright. My rounded Afro frizzed around my head like an electricity experiment gone wrong.  Oh, and that was the year I got braces. Mercifully, I thought to remove the humiliating headgear I had to wear with them before the picture was snapped. Headgear apparently was a leftover of torture from the Middle Ages: a metal bar that wrapped around your face, attached to your back teeth, and harnessed around the back of your neck by a velcro strap. And, again with the mustard yellow color. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that the Color Me Beautiful concept came around and I learned that yellow was not, and never would be, my color. It made me look as if I were just getting over a nasty stomach bug. Seventh grade was not my finest moment.

Oh, and that was the year I got braces. Mercifully, I thought to remove the humiliating headgear I had to wear with them before the picture was snapped. Headgear apparently was a leftover of torture from the Middle Ages: a metal bar that wrapped around your face, attached to your back teeth, and harnessed around the back of your neck by a velcro strap. And, again with the mustard yellow color. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that the Color Me Beautiful concept came around and I learned that yellow was not, and never would be, my color. It made me look as if I were just getting over a nasty stomach bug. Seventh grade was not my finest moment.

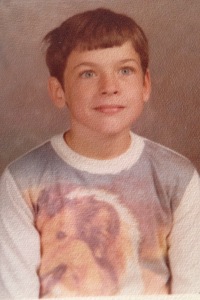

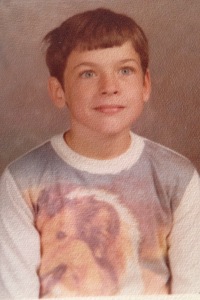

My husband had a classic school picture, too. His was captured in 3rd grade, when he apparently was having a bit of a bad hair day. There’s a note in his childhood scrapbook, written by his mom, that reads, “didn’t think to tell mom we were having pictures made.” That might explain the Lassie shirt and his seemingly stunned expression.

My husband had a classic school picture, too. His was captured in 3rd grade, when he apparently was having a bit of a bad hair day. There’s a note in his childhood scrapbook, written by his mom, that reads, “didn’t think to tell mom we were having pictures made.” That might explain the Lassie shirt and his seemingly stunned expression.

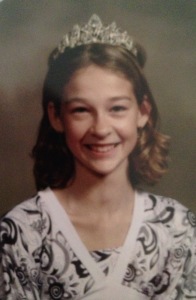

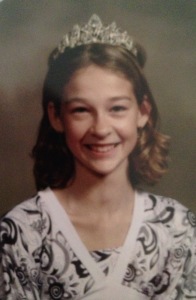

With our sad history of school pictures, I was determined to shepherd my children through the pitfalls of forever having such images represent themselves. When my daughter turned 11, she deemed the day her long-awaited “Golden Birthday.”  No idea where she came up with this, but apparently turning 11 on the 11th is somehow your life’s one magical date. (I guess I missed the significance when I turned 14 on the 14th; no magic for me.) Turns out, her magic day fell on picture day. Imagine my surprise when the pictures finally came back and I realized she’d chosen to immortalize the moment forever by way of a tiara. Future students leafing through the old school yearbooks will not be aware of her reasons and will just imagine she was 6th grade royalty. Perhaps this was her plan all along. Why didn’t I think of that in 7th grade? Then again, the tiara would have been swallowed by my giant hair.

No idea where she came up with this, but apparently turning 11 on the 11th is somehow your life’s one magical date. (I guess I missed the significance when I turned 14 on the 14th; no magic for me.) Turns out, her magic day fell on picture day. Imagine my surprise when the pictures finally came back and I realized she’d chosen to immortalize the moment forever by way of a tiara. Future students leafing through the old school yearbooks will not be aware of her reasons and will just imagine she was 6th grade royalty. Perhaps this was her plan all along. Why didn’t I think of that in 7th grade? Then again, the tiara would have been swallowed by my giant hair.

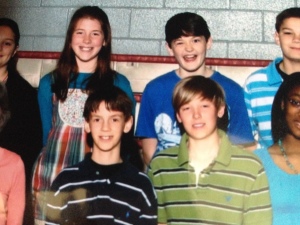

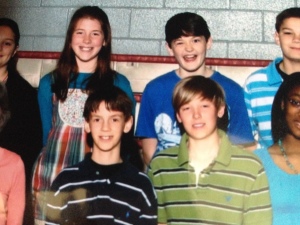

Sadly, my son’s Golden Birthday will not come until he turns 26, long after the school picture opportunity has passed. He has never taken picture day seriously. It has always  been a barrage of reminders to please comb your hair and try a decent smile. In fifth grade, it wasn’t just his own self portrait that he decided to flub. He managed to wait for just the right moment in the class picture to be a goof. Yep, that’s him in the blue shirt looking like Bill the Cat from the Bloom County cartoon. The other parents, when they received this little gem, may have been startled by what appeared to be the child choking in the back row.

been a barrage of reminders to please comb your hair and try a decent smile. In fifth grade, it wasn’t just his own self portrait that he decided to flub. He managed to wait for just the right moment in the class picture to be a goof. Yep, that’s him in the blue shirt looking like Bill the Cat from the Bloom County cartoon. The other parents, when they received this little gem, may have been startled by what appeared to be the child choking in the back row.

I was thinking the other day that, now that homeschooling is on the rise, many students will be able to escape the ignominy of school pictures. And with all the digital technology available, at the very least, they could photo-shop out the weird kid in the back row of a group shot.

Despite the embarrassment at the time, I kind of like having the old school pictures available. I can show my kids that I wasn’t always the specimen of beauty and coolness that they envy today. Everyone is weird. Everyone has been humbled, hated the way they looked, did something dumb, had a period of awkwardness. It’s a universal path that all of us must walk. The edited, filtered, photo-shopped selfies of today are just an illusion. I love Colbie Callait’s song “Try” because she says it’s okay to be real, genuine, messy, and likable anyway.

That’s why, towards the end of my kids’ school years, my favorite pictures have turned out to be the ones where their silliness and fun outweigh their outfits or hair or smiles. It’s why, when I pulled out my 7th grade picture and warned my son to shield his eyes and not look at it directly, we both shared a laugh at just how awful it was. We’re just keepin’ it real, people.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 17, 2015 | Thoughts

Time is marching on and I’m feeling that familiar pressure to forcefully cram lovingly impart all my Wisdom to my son before he’s on his own. A week has gone by and I have made exactly none of the healthy, good-for-you recipes from Pinterest I vowed to try. The bathroom scale mocks me each morning as I step out of the shower. It’s the middle of February and the fragile optimism I held so gently in my hands at the start of the year has started gasping for air as I realize several of my goals for 2015 have yet to see progress.

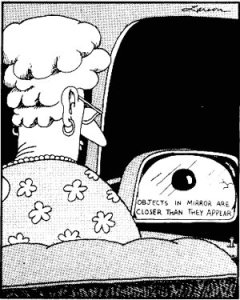

Gary Larson has a classic Far Side cartoon that illustrates how I’m feeling. When I’m focused on meeting all the expectations, trying to keep my eyes on the 16 different balls I’m juggling, all of a sudden there’s a startling eyeball coming up on my right. Objects in mirror are closer than they appear? Yikes!

Gary Larson has a classic Far Side cartoon that illustrates how I’m feeling. When I’m focused on meeting all the expectations, trying to keep my eyes on the 16 different balls I’m juggling, all of a sudden there’s a startling eyeball coming up on my right. Objects in mirror are closer than they appear? Yikes!

When my kids were young, this eyeball was all the stuff I wasn’t doing, catching up to me. The day would start out with such promise and I had so many things I’d want to accomplish, but it could (and usually did) turn on a dime. All my best intentions forgotten, I’d be struggling through the grocery store with frozen food piled on top of my daughter in the basket while my son gummed handfuls of crackers into a soggy mess down the front of his shirt.

Inevitably, some random sweet older woman would give me that look in the checkout line, and I’d think, “Uh-oh, here it comes.”

“Look at your sweet angels. You should treasure each moment, honey. It all goes by in a flash. They’re only like this for the blink of an eye.”

“Really?” I’d think, “because last night when I was changing wet sheets at 2 a.m. it seemed like an eternity.”

The same thing would happen when I was in the middle of the daily exorcism that was my life with a teenage girl. Women who’d been through it with their own offspring would tell me it was just a phase and all but pat me on the head. Oh, a phase? You mean like werewolves go through when they shape-shift? Cool.

What I needed, what I think all moms really need at the core, instead of a wise wink and platitudes that this, too, shall pass and pass quickly, is acknowledgement that what I was doing was hard. The hardest. Physically exhausting, emotionally draining, repetitive, often unrewarded work. I would have preferred a thumbs up, a conspiratorial nod, like they understood that I was doing my best, despite the screaming and tears (from me, not my toddlers or teens).

I was in the mall food court the other day with my teenage son, and it was so crowded we shared half a table with a young mom and her three little ones. The oldest, maybe 4, was up and down after each bite of lunch, kneeling, squirming, and twirling in his seat. It was just a matter of time before he slipped and fell–and I automatically caught him, hands smeared in ketchup, before he hit the ground. His mom was so apologetic. She’d been tending to her baby on her other side when he fell.

“It’s ok,” I said and gestured to my man-child son across from me. She gave me the most grateful look and said, “Yes, so you know. Except he’s big now!” We shared a laugh and I helped her clean up the ketchup all over the table. I didn’t tell her that her kids would not be little like that for long.

Because it’s universal: all moms want is someone to tell us we are doing ok even when it looks like it’s all falling apart. There is no reminder that can guilt her any more than she’s already guilting herself. There is no criticism you can speak that she hasn’t already spoken a hundred times. She’s constantly second-guessing and blundering her way through parenting the best she can, having moments she’s not proud of and moments that she’d never thought she’d be strong enough to endure.

She’ll figure out on her own that the days are long, but the years are short. Those thousand things that seem to be bearing down on you inevitably change into a sense of time passing too quickly.

Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear.

They creep up on you and take your breath in surprise. I look in the rear-view expecting to see my toddler son and suddenly there he is all biceps and big feet, the sweet voice that used to sing Itsy Bitsy Spider now cracking as it strains towards a new sort of bass sound. I call my daughter some days imagining her twirling and skipping and am blown away by her independence and self-assurance.

I used to sing a Hans Christian Andersen song as a lullaby to my children every night.

Inchworm, inchworm,

Measuring the marigolds.

You and your arithmetic will probably go far.

Inchworm, inchworm,

Measuring the marigolds,

Seems to me you’d stop and see how beautiful they are.

(2 and 2 are 4, 4 and 4 are 8, 8 and 8 are 16, 16 and 16 are 32)

It was a good daily reminder, after the grocery stores and the arguing, to stop a minute and really look at my kids, drink them in with all their gifts and strengths and failures and faults.

It was a good daily reminder, after the grocery stores and the arguing, to stop a minute and really look at my kids, drink them in with all their gifts and strengths and failures and faults.

Of course the women were right–we should all treasure the moments. But if we aren’t carpe-ing each diem with zest and glee, it doesn’t mean we have failed. If we stood in awe and amazement during all the moments of every day, we wouldn’t really be honestly living those moments. Instead, we’d be standing around goggling at the beauty and sweetness and letting some important work slide. It’s only in hindsight, no matter how many reminders you get from the well-meaners, that you see the golden field of marigolds you’ve tended.

As Solomon observed, there’s a time and season for everything. A time for tantrums and a time for lullabies, a time for hissy fits and a time for shared confidences. A time for savoring and a time for soldiering, eyeballs and inchworms.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 8, 2015 | Thoughts

Back when my children were toddlers underfoot, there were many days when I heard a constant stream of alternating chatter, screaming, laughing, whining, crying, and singing. Back then, Barney and Dora played incessantly as the soundtrack of my life. I fielded endless “whys” from sunup to sundown. Why I hafta go sleep? Why did Hiccup the hamster die? Why is Dora’s head so big? (That one will have to remain one of the universe’s mysteries.)

Some evenings, after failed attempts at playing “Quiet as a Mouse,” I just had to blurt, “Mommy’s ears are really tired! Can we give them a little rest for a few minutes?” Back then, I would have paid big bucks for five minutes of quiet alone in the bathroom, and nap times were manna from heaven. I mainlined the quiet and stillness like a heroin addict.

Now that one of the children is off to college and the other is completely independent and often doing homework or in his own world wearing headphones at a computer screen, the quiet I longed for has arrived. And it brought along its friends, anxiety and restlessness. The silence prods me: is there something you should be doing? Someone you should be looking after? Where’s that list of To-Do’s and action items?

While I don’t mind the quiet, I’m not very good at it. I come by it honestly. I’m pretty sure I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen my father sit down and just relax. I’m not sure he gets the concept, really. He’ll go on vacation to visit one of his kids and end up patching our drywall, repairing a privacy fence, or installing a ceiling fan. He doesn’t stay in one place for very long. After a couple of days, he’s ready to get back on the road. Things to do, places to go. You know these people. Often they are our mothers or grandmothers, who slaved over holiday feasts only to be bobbing up and down from the table like the Whack-a-Mole game, their own dinners untouched and cold.

A few years ago, I learned of a piece of music composed by John Cage in 1952. It’s called 4’33”, and it consists of three movements entirely of rests. The performer appears on stage, sits at the piano to begin while the audience waits in anticipation, and then nothing. Four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. The pianist counts all the measures of rests as the audience squirms. What is going on? Did he forget the music? Does he have stage fright? People look at one another nervously.

Four minutes and thirty-three seconds is a long time to be quiet. Just ask a toddler playing “Quiet as a Mouse.” Eventually, you start to listen, not to the music, but to the absence of it: the creaking of the seat cushions, a cough, someone’s whisper, the rustle of a program. You’re forced to settle in, get past the initial discomfort, and hear a different sort of music in your surroundings. Even the sound of your own breath becomes a choir of its own, filling the empty air with notes of spontaneous melody.

There is a beauty that arises from stillness, from silence, that we often disregard because it’s not as urgent or demanding as noise. It’s like the well-behaved child reading by herself who gets no attention because the rowdy cousins are swinging from the drapes in the other room. The dearest of friends are those who can sit still with you in the hospital waiting room, those who don’t have to keep up a barrage of chatter lest the room grow uncomfortably quiet. There are tense silences (when you’ve just laid the baby down and are tiptoeing soundlessly out of the nursery like a ninja) and easy, comfortable ones (when you’ve turned in for the night with your spouse and you’re both reading in bed companionably, conversation optional).

What this new-found quiet at my house has taught me is that I haven’t practiced it very much. Silence and I haven’t spent much quality time together. My day is usually full of conversations, phone calls, TV, traffic, the car radio, podcasts, itunes, even a running commentary in my own head, much like those from my kids that used to make my ears so tired. Even if I’m sitting quietly, I’m occupied with a book or my phone.

I know I’m not alone in this. Aside from the technology addiction that many of us have (admitting you have a problem is the first step to recovery, people!), we don’t know how to sit still in the quiet and just be. We demand constant entertainment, distraction, busyness, and noise, which is why the 4’33” concert piece so unnerves audiences. I have to wonder what we are so afraid of? What do we think will fill the quiet if we let it happen? If we turn off the car radio while we’re running errands, what rushes in? If we sit quietly for a few minutes without scrolling through Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or YouTube, what thoughts arise?

Richard Foster’s Celebration of Discipline elaborates on the practice of silence as a spiritual discipline. As with most things spiritual, if you empty yourself of one thing, something else takes its place. Empty yourself of noise and silence settles upon you, often bringing its own kind of disquiet. What thoughts are there, lurking beneath the noise? I’ve been practicing being quiet, enjoying the silence, hearing what’s already there instead of injecting my own noise into the universe.

All the noise is exhausting, and we don’t even realize it until it’s absent and we breathe deeper and our shoulders relax. Without the car radio on, once I run through my own stream of consciousness thoughts, the quiet often leads me to prayer. “Well, I pray,” you say. “I’m so disciplined I even have a quiet time every morning, just me in the quiet before the day starts.” Awesome. You’re way ahead of me. But prayer is a conversation, not just you phoning in your thoughts or requests. Often we just yak away and forget that there’s a second act. Being still and knowing. Listening in the quiet. If you don’t think that there might be an answer, then why waste your time in prayer? No telling what might bubble up from the quiet and surprise you. The still, small voice is awfully hard to hear when you drown it out.

In the movie Get Smart, one of the coolest gadgets was the Cone of Silence. Once under it,  all noise completely stopped, like inside a vacuum. Being a silence rookie, I wish I had one of these convenient devices that I could activate whenever I need a “moment of silence.” (There I go, dependent on technology again.)

all noise completely stopped, like inside a vacuum. Being a silence rookie, I wish I had one of these convenient devices that I could activate whenever I need a “moment of silence.” (There I go, dependent on technology again.)

I still appreciate some noise in my days. I like a good car jam as well as anyone (celebration is also a spiritual discipline, by the way)! But I’m learning through my circumstances and newly quiet house to appreciate the silence and the lessons it teaches.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Feb 5, 2015 | Thoughts

These cold February days have me day dreaming about my Floridian childhood. Most of my formative years were spent on Florida’s Space Coast, the stomping ground of Major Nelson and Jeannie from the 1970’s I Dream of Jeannie show.

We lived just a few blocks from the ocean, although we rarely went. Hard to believe now that we actually schedule family vacations for that very purpose, but familiarity breeds contempt, I suppose. Our beach was rocky and full of seaweed and many times was a minefield full of clumps of sticky tar that was impossible to scrub from your feet. Still, we would sometimes be lucky enough to spot a loggerhead turtle laying her eggs, scooping sand with her flippers to cover the nest before heading back out to sea.

Our zip code designated our address as Satellite Beach, about an hour south of Orlando and central Florida’s tourist Mecca. We had Florida resident and military discounts to Disney and Sea World, so I lost count of how many times we were there. Once I got older, my friends and I got dropped off at the gate a few times by our parents, kind of like the mall hangout for today’s crowd, except instead of Hollister and the Cookie Store, we got Mickey and Shamu. Space Mountain’s roller coaster in the dark was our version of living on the edge.

The Magic Kingdom wasn’t the only magical aspect of my childhood. Where the Indian and Banana Rivers converged in south Merritt Island,

dragon point, “Annie”; from Florida Today

there was a huge mansion at the island’s tip. There used to be a 20-ton statue of a dragon (named Annie) that jutted out into the water, as if she were scooping up minnows from the shallows. Every time we passed that dragon, I’d dream up stories about her life and what she did there. I heard just recently that the mansion is being repaired and the dragon restored–hurray!

We had no seasons: shorts and flip flops at Christmas, shorter shorts and bare feet in the summer. Palm trees stayed the same all year. The only way you knew the holidays were approaching was the change in inventory at the stores. The first winter after moving away, my freshman English teacher stopped class to let me go outside in the snow that was drifting down. I’d never seen snow that I remembered, and she thought it was high time. Summer must be over because school would start up again, and people wouldn’t run the sprinklers in their yards as often. This was a good thing since we were constantly outside sprinting through our neighbors’ yards, and you never knew when their timers would be set to come on, soaking you with smelly sulfur water in the middle of a good game of tag.

Periodically, NASA would announce a rocket launch, and we’d hurry through dinner so we could sit on the picnic table in the backyard and watch it light up the sky, a vertical plume of flame and smoke trailing from its tail as it sped towards its orbit. For really important ones, we’d head to the beach and sit on the sand, listening in the dark for the familiar bass rumble. It was better than a fireworks show. On their way back from Japan after I was born, my parents had watched on the airport TV screens as the Apollo 11 astronauts took their first steps on the moon. About 13 years later, one afternoon when I was in gym class, we looked up to see the Shuttle Columbia and its escort jets flying home to Kennedy Space Center after its recent landing in California. It flew so low I could make out the windows on its side, and we all cheered and waved.

In January of my senior year, I was in Tennessee home from school for a snow day watching TV as the Challenger exploded in mid-launch. We felt it personally, having watched it launch several times from our backyard. One of my sisters worked at Cape Canaveral, where the loss was traumatic and the effects were felt for years afterward.

When we weren’t peering up at the night sky, we were running barefoot in the sunshine. For a time, my family had a boat that we’d take out onto the Indian River. We’d motor under the drawbridges and through the canals, winding our way to the many islands that dotted the river’s landscape. I loved to putter alongside a gently floating school of manatees, their gray backs breaching the surface like ancient whales. Occasionally we’d hand-feed them heads of iceberg lettuce, their whiskery faces peering at us while they munched.

my brother & me, an afternoon on the water

We would anchor at one of these outcroppings and pile out with the day’s lunch and our portable grill. We learned how to dig in the wet sand at the water’s edge with our toes, finding clams that we’d toss on the grill until they popped open, revealing their salty, slightly gritty meat.

I learned to love seafood. My grandfather owned a charter deep sea fishing boat in Panama City, and we’d regularly stock up on fresh-caught grouper and snapper. My parents would go out at night with friends and throw nets from the bridges, hauling in all-you-could-eat shrimp. My dad had a tour of duty assignment in the Grand Turk islands, and he would bring back coolers of conch and lobster, packed on ice. It wasn’t until I was much older that I realized, sadly, that lobster wasn’t an every-day menu item.

One of my friends had a small two-man sailboat. We were not yet old enough for a driver’s license, but she could pilot the little craft around the canals, through the watery backyards of the neighborhood. That was all the freedom we needed, sans wheels.

My father was anxious to leave. Being raised in Wisconsin and Maryland, he couldn’t stand the summer heat. He constantly muttered about the cars, our bikes, and his tools rusting because of the salt air from the ocean breeze. We had to time our exits from the house so as to open the door the minimum amount of time possible, edging through in the briefest of seconds or else he’d yell, “Shut the door!” Obviously we were trying to air condition the entire neighborhood! We were also not allowed to turn on the oven for this reason. The a/c ran constantly, turning him into a miser who constantly monitored the thermostat. But kids don’t see the adult reasoning behind all that frustration. My Florida was an oasis of warmth and ocean breezes, punctuated by the occasional hurricane. We rode our bikes for miles over the flat terrain: to and from school, the library, the movies, friends’ houses. It was a freer time then, before kids were monitored every second through scheduled play dates and after-school activities. We had to be back to our neighborhood before the street lights came on and close enough to hear my father’s whistle for dinner time.

Three of my siblings still call Florida home, so I can easily visit. I have the best of both worlds, with the occasional snowfall and hardwood trees that turn glorious in the fall here and a means to answer the Siren’s call of the ocean whenever I feel the pull. Like, for example, on gray February days like these.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 29, 2015 | Thoughts

In the spring of 2013, the KKK held a rally in Memphis protesting the renaming of some parks named for Confederate notables. This lingering blight of racism is one of the few things I dislike about where I live, but fortunately I usually only encounter it in small pockets of my state.

Although I heard ugly remarks from my grandparent’s generation, my parents didn’t raise us that way. In South Carolina we lived on a diverse military base, and my sisters would bring friends by the house, some of them black. My brother was maybe 3 or 4 at the time, and he was fascinated by the difference. He toddled over, repeatedly rubbing the arm of one of their friends once, bewildered. “Why he dirty?” he asked my sister, thinking if he just rubbed hard enough the black would come off. The boy thought it was hilarious, despite my sisters’ embarrassment.

I suppose because of this sort of thing, we talked about differences a lot, and I learned early about equality and race. My mother hailed from rural Alabama during the 40’s and 50’s and had formed some firm ideas about how people should be treated. She was ahead of her time on that issue. I often heard her talk passionately about civil rights, feminism, and WWII’s holocaust. People are people, she used to say. She didn’t cotton to some older ways of thinking. As a result, my hackles always rise when I hear an off-color remark, and I can get pretty heated over stereotypes.

Which is why my husband, son, and father-in-law were astounded to see my van parked on the edge of a secret KKK meeting close to our neighborhood. It was the same weekend as the Memphis rally, and the boys had just driven by a wooded area where white-hooded figures were circled in the woods just off the road. Alarmed, Bob turned his truck around, ready to come rescue me because he just knew I’d gone storming into their midst with righteous indignation, and he imagined my horrible fate. Just as they were about to pull into the field, it dawned on him. That morning I was attending a beekeeping class, and we had gone into the field to get some hands-on hive experience. Beekeepers wear white suits and white hats with veils. We were circled around a hive, watching our instructor install a new queen into a hive in the woods. I wasn’t even aware the heroic trio had been there until I walked into the house after the class and they burst out laughing, relaying their mistake.

There’s a great chapter on race in Bronson & Merryman’s book Nurture Shock (2009) that surprised me. White parents tend to think that by not pointing out differences and making general statements like “everybody’s equal,” or “God made everyone” we are raising color blind children. Young children have an innate developmental need to categorize everything to make sense of the world. If you haven’t specifically pointed out differences and explained them, they will create their own divisions–“those like me” and “those not like me.” Think about how we talk about gender (mommies can be doctors and firefighters just like daddies), but we are often silent about race unless we are forced into it by explaining an international adoption or interracial marriage. To a child, our silence on the matter leaves them to identify with (and prefer) those most like him. What this means is that racism is not necessarily taught. It’s an inference that’s made from an early age (way before 3rd grade) because no one mentioned and corrected it.

In minority families, race is discussed more, but it’s often in the context of preparing a child to face discrimination. Sadly, some of this talk is still necessary in our culture. But too much of it tends to be as negative as actual experiences of discrimination. Instead of connecting their success to effort, children who hear this sort of thing frequently tend to blame their failures on others because they see others as biased against them.

A few years ago, we spent some time with friends in Tanzania, Africa. It was a disorienting reversal of culture, as we became the racial minority. We were pointed at in the market, people saying, “Mzungu!” (Swahili for “white person”). Small children were often afraid of us. They’d never seen a white person before and thought we were ghosts. In these areas, children born with albinism (pale or white skin) were often attacked, their limbs severed for witch-doctor practices. This was fear of the “other” at its most basic level.

We were most definitely “not like them.” At least on the surface. Once the children saw their images on an iPhone camera, their curiosity overcame fear. It was pure joy watching my son and a small boy interact, swapping hats and laughing at each other in the shared language of play. People in the village wondered at our skin, our different hair, and especially the braces on my son’s teeth. Once I sat on the dirt floor of the hut with the other women, sifting rocks out of the rice that was to be our lunch, color became irrelevant as we all shared the communal work of women the world over–feeding our families and watching over the children–not so different after all.

Another village invited us to share in a worship service in their community church. Although the entire thing was conducted in Swahili and Sukuma, we followed along easily with the spirited singing and prayers. Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight, Jesus loves the little children of the world. The simple children’s song echoed in my head with the beauty of our fellowship.

one of these things is not like the others…

Not so different after all.

I find all the research about race fascinating, especially in light of the racially charged controversy between police and minority communities that’s played out all over the media in the past year. Obviously a remote village in Africa is not equivalent to the streets of American cities. Even so, if we took the time to see each other with different eyes, to recognize our common humanity, surely we would walk a few steps further towards one another and away from our fearful “not like me” instincts.

You don’t need to travel across the globe to teach your children that people are people. Certainly a key way to make a difference and affect change is to start talking–early and specifically–to our young children. They need to know that we are aware of differences and that it’s okay to talk about them. Just like gender, it’s only surface stuff. Underneath, we all want the same things and have the same feelings.

Not every hooded person is sinister.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jan 25, 2015 | Thoughts

A couple of years ago we took a trip to New York City. We got a great guide book, marked off the tourist spots we wanted to see, made some reservations, and set off, intrepid travelers full of expectation. And expectations were met. After JFK spewed us from its terminal, we held on for dear life in a dirty yellow taxi clearly driven by a madman.

Sweating and breathless, I gasped at the near misses and close calls with cars and bicycles as we weaved our way to our hotel. As much as possible, I craned my neck this way and that, trying like a sponge to absorb the city view. Apartments running from block to block, laundry hung from the railings and fire escapes; lines of uniformed children on their way to a field trip at the museum on the corner; bricks, asphalt, concrete; shop windows full of women’s clothing, street carts offering a quick tasty lunch; glassed-in buildings stretching tall, so high you couldn’t see the tops without tipping your head back and back until dizziness set in. So much to see!

One of my best childhood friends works in a building in Times Square. Once we left our hotel and made our way to her office, we stood in the middle of the block, turning like rotisseries, goggling at the lights, colors, costumed performers, and advertisements, each boasting more movement and neon than the last. It was exhausting, the definition of sensory overload.

We entered her building and it was as if we’d stepped into an alternate universe. The vacuous lobby echoed with the clack of polished heels. Overhead lights reflected on the chrome and glass in muted shades of gray and sophisticated ivory. I felt myself relax from the absence of sensory onslaught. My friend was dismissive of the display just outside the doors. She waved her hand and rolled her eyes. “This is just for the tourists,” she said. “If you live here, it’s kind of embarrassing.” She gave us pointers on what to see for the afternoon and suggested we download KickMap, a great app for navigating the subway. “Also,” she said, “Use Maps on your phone for when you come up out of the stations. It can be disorienting.”

Duly armed, we made our way to the nearest station and set off for our first tourist site. We must have walked miles that day, jostling with other pedestrians: all nationalities and colors, crowds of tourists, students from NYU, women in business suits and tennis shoes, hoofing to their next destination, high heels stowed in their designer bags. Up and down into the subway stations we went, going from the gusty winds and sirens above to the stuffy, graffiti-ed tunnels below. Every time–EVERY time–I emerged from the steps onto the street, pushed by the flow of people, my neck swiveled like a dizzy owl as I tried to get my bearings. Which street was this? Which direction were we headed? I’d consult the Maps app on my phone, watch the blinking beacon that was “me” as I walked, and nine times out of ten I’d be headed the wrong way.

the wrong way.

Admittedly, a sense of direction was not one of my gifts. When I was a kid, the compass rose on the top of a map caused me no end of confusion. North was always at the top, so I reasoned that it was always in front of me. Whichever direction I faced as I held the map, no matter where I was standing, would always be North. East was always to my right, South always behind. My disoriented brain did not comprehend that the directions were constant, while I was the one changing. At dinner parties, my father would call me over and ask which direction I was facing. “North,” I would say, exasperated, “Always North!” (Ok, so I was never in Girl Scouts.)

At the end of our sight-seeing day, we came up out of a subway station and a woman kept pushing my shoulder from behind, saying “Excuse me.” I kept edging out of her way, but she kept pushing until I began to feel nervous and hug my purse tighter. When I finally turned my head to give her a “back off, lady” look, I realized why she persisted. She was blind. She was in her mid 60’s, short with frizzy brown hair, and had a heavy New York accent. She clearly expected me to do her bidding. I turned to her, and as she sensed my posture change, she hooked her arm in mine. “Can you point me in the direction of East 125th?”

I was already fumbling with the apps on my phone. I stammered, “I’m not actually from here.” She had no patience with my incompetence. “I know where I’m going,” she huffed, “Just point me in the direction. I don’t know how this subway comes up.” By some miraculous stroke of luck, I happened to spot a street sign that was where she wanted to go. I took a couple steps in that direction and told her that was the way. She unhooked her cane from her free arm and set off confidently, her face tilted slightly up and to the left, as if she were listening to a pleasant melody.

I stood there stunned, my destination forgotten. All I could think was how confused I’d been all day, the distances I’d traveled, the sights I’d seen, the swirl of color and lights in Times Square. How I could barely navigate my way a few blocks with the repeated use of maps and constant landmark checking. You know that game where you’re blindfolded and spun around and then asked to hit the hanging pinata? She lived that every day. Except instead of whacking a paper donkey for candy she was making her way through the congested streets of one of the biggest cities in the world.

She amazed and humbled me, this stranger, in our brief encounter. While my husband and kids stood huddled over their phones, debating over which way we should head, I leaned back against the rough brick of a corner building and shut my eyes. I imagined the life the woman might lead, and tried to distinguish direction without any visual cues. The city’s sensory attack was definitely thwarted without sight. With the sirens, honking taxis, cell phone conversations, and footsteps, I couldn’t discern any helpful pattern. Smells: hot dogs, sewage, someone’s bold choice of cologne, exhaust fumes. Opening my eyes in panic, I realized how brave she was, not even a service dog to help guide her.

During the rest of our stay, I noticed the streets differently. I marked the neighborhoods not by sight but tried to distinguish them by sound or smell. The perfume of the flower stall on the corner, the spicy Thai restaurant, the quiet conversation of the old men playing chess by NYU, a solo saxophonist making music under a bridge in Central Park. It was a game, eavesdropping on the city, trying to decipher the clues of my surroundings. I let the family navigate by sight as I trailed along fascinated by the city’s other senses.

How ironic that a blind woman would have added such depth to my sight-seeing. I still can’t find my way out of a paper bag. But when we travel now, I frequently pause to appreciate the non-visual aspects of a new place, to think how I would describe it to someone without sight. That day, we were each an example of the blind leading the blind. I’d thought I was taking in the city in all its glory, but she showed me a deeper way to “sight see.”

them is their wallet-sized school picture, frozen in 4th grade forever. Inevitably, every school year couldn’t be as cute as that one with the toothless grin in first grade. In fourth grade, I conveniently broke out with a case of cold sores–all over my face. Also, that was the day I wore the flattering bright yellow sundress my mother made me. All my friends who moved away that year have that lovely image to remind them, forever, of me.

them is their wallet-sized school picture, frozen in 4th grade forever. Inevitably, every school year couldn’t be as cute as that one with the toothless grin in first grade. In fourth grade, I conveniently broke out with a case of cold sores–all over my face. Also, that was the day I wore the flattering bright yellow sundress my mother made me. All my friends who moved away that year have that lovely image to remind them, forever, of me. Oh, and that was the year I got braces. Mercifully, I thought to remove the humiliating headgear I had to wear with them before the picture was snapped. Headgear apparently was a leftover of torture from the Middle Ages: a metal bar that wrapped around your face, attached to your back teeth, and harnessed around the back of your neck by a velcro strap. And, again with the mustard yellow color. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that the Color Me Beautiful concept came around and I learned that yellow was not, and never would be, my color. It made me look as if I were just getting over a nasty stomach bug. Seventh grade was not my finest moment.

Oh, and that was the year I got braces. Mercifully, I thought to remove the humiliating headgear I had to wear with them before the picture was snapped. Headgear apparently was a leftover of torture from the Middle Ages: a metal bar that wrapped around your face, attached to your back teeth, and harnessed around the back of your neck by a velcro strap. And, again with the mustard yellow color. It wasn’t until the late 80’s that the Color Me Beautiful concept came around and I learned that yellow was not, and never would be, my color. It made me look as if I were just getting over a nasty stomach bug. Seventh grade was not my finest moment. My husband had a classic school picture, too. His was captured in 3rd grade, when he apparently was having a bit of a bad hair day. There’s a note in his childhood scrapbook, written by his mom, that reads, “didn’t think to tell mom we were having pictures made.” That might explain the Lassie shirt and his seemingly stunned expression.

My husband had a classic school picture, too. His was captured in 3rd grade, when he apparently was having a bit of a bad hair day. There’s a note in his childhood scrapbook, written by his mom, that reads, “didn’t think to tell mom we were having pictures made.” That might explain the Lassie shirt and his seemingly stunned expression. No idea where she came up with this, but apparently turning 11 on the 11th is somehow your life’s one magical date. (I guess I missed the significance when I turned 14 on the 14th; no magic for me.) Turns out, her magic day fell on picture day. Imagine my surprise when the pictures finally came back and I realized she’d chosen to immortalize the moment forever by way of a tiara. Future students leafing through the old school yearbooks will not be aware of her reasons and will just imagine she was 6th grade royalty. Perhaps this was her plan all along. Why didn’t I think of that in 7th grade? Then again, the tiara would have been swallowed by my giant hair.

No idea where she came up with this, but apparently turning 11 on the 11th is somehow your life’s one magical date. (I guess I missed the significance when I turned 14 on the 14th; no magic for me.) Turns out, her magic day fell on picture day. Imagine my surprise when the pictures finally came back and I realized she’d chosen to immortalize the moment forever by way of a tiara. Future students leafing through the old school yearbooks will not be aware of her reasons and will just imagine she was 6th grade royalty. Perhaps this was her plan all along. Why didn’t I think of that in 7th grade? Then again, the tiara would have been swallowed by my giant hair. been a barrage of reminders to please comb your hair and try a decent smile. In fifth grade, it wasn’t just his own self portrait that he decided to flub. He managed to wait for just the right moment in the class picture to be a goof. Yep, that’s him in the blue shirt looking like Bill the Cat from the Bloom County cartoon. The other parents, when they received this little gem, may have been startled by what appeared to be the child choking in the back row.

been a barrage of reminders to please comb your hair and try a decent smile. In fifth grade, it wasn’t just his own self portrait that he decided to flub. He managed to wait for just the right moment in the class picture to be a goof. Yep, that’s him in the blue shirt looking like Bill the Cat from the Bloom County cartoon. The other parents, when they received this little gem, may have been startled by what appeared to be the child choking in the back row.

the wrong way.

the wrong way.