by bsquared5@aol.com | Dec 15, 2014 | Thoughts

The best Christmas gift I ever received wasn’t a Christmas gift at all, but a spontaneous, compassionate gesture from a friend of a friend. When I was a kid, if you came running into the house all hot and sweaty from playing outside in the Florida heat, it was a good bet you could find my mom in front of her sewing machine, probably with some Anne Murray playing on the stereo.

The best Christmas gift I ever received wasn’t a Christmas gift at all, but a spontaneous, compassionate gesture from a friend of a friend. When I was a kid, if you came running into the house all hot and sweaty from playing outside in the Florida heat, it was a good bet you could find my mom in front of her sewing machine, probably with some Anne Murray playing on the stereo.

She, like her mother before her, made things: all of our curtains and throw pillows, assorted matching dresses for my sisters, dolls and Santas, bunnies and birds. The tip of the middle finger on her left hand was a rough, pitted mess from hand-stitching quilts from leftover fabrics that were stacked in bins in her sewing room. When she brushed and smoothed my hair, that finger would always snag and catch on a few strands.

She sold some of these creations in a local shop and did some by special order for weddings or showers. Old metal tins full of buttons and other sewing notions were stacked on the shelf above her machine. My dad, always handy, made a pegboard where she hung ribbon, thread, and other mysterious trappings of her craft like scissors with notched edges, bobbins, and colored chalk for marking patterns. He fashioned a whole organized storage system out of little International Coffee tins, which were mounted on a shelf, their plastic lids revealing the contents. I would sit reading or doodling at her feet listening to the rhythmic buzz-buzz-buzz of the sewing machine as she worked. I imagined stories of British children named Simplicity and Butterick, named after the patterns filed in boxes under her table. We’d spend hours like this, until she’d glance at the clock and see it was almost time for my father to get home. She’d push aside what she’d been working on and head for the kitchen to start dinner.

I never learned a single stitch. In junior high I had a home economics class (do they even have those anymore?) where I had to make an item of clothing. My halter top was uneven and hung crooked, and that was after hours of tears of anger and frustration. She did manage to show me how to sew on a button, my one sewing ability. But sitting at the sewing machine and pushing that foot pedal that made the needle go up and down at a dizzying speed reminded me of my father’s table saw and conjured thoughts of heinous injuries. I just couldn’t do it.

Twenty-one years ago in October we lost mom to cancer. Two months later it was Christmas time and unthinkable to get together for family celebrations without her. I was mopey and depressed, angry that people had the nerve to just keep marching right on shopping and baking and decorating when for me, the whole world had just come to a screeching halt. Joy to the World? No way.

My best friend was home for the holiday, and we ended up at her house. I think we were supposed to pick some of her sister’s friends up and go see a movie, not that there was anything worth seeing. The Edlin’s lived across the street from my friend. We walked over in the cold December night and knocked on their festive holiday door. I tried my best to be friendly, or at least civil, while we waited for everyone to get their coats. I felt isolated and lonely, even (or especially) amid the crowd, and I wandered off to look at their Christmas tree sparkling in the corner.

Mrs. Edlin (Helen) must have seen me there and she came over to give me a hug. It was then I noticed them. On her tree were two of my mother’s doves–one red, one white. Immediately I was transported back to underneath the sewing machine, seeing my mother’s hand-drawn patterns of the little birds and the bin of wings just waiting to be attached. “Oh!” I said, “My mom made those!” They were some of her best sellers–all sold out around town.

She nodded. “I found them at the shop by the park,” she said. “They were so cute.” I didn’t register what she was doing as she unhooked them from the tree. She held the pair of doves in her hands. “Of course you need these,” she said, holding them out to me.

She had no idea as she handed them over that she’d just given me back Christmas. That simple, unselfish gesture melted some of the ice that had been growing steadily thicker around my heart. Without words, I gave her a tearful hug as a thank you, completely inadequate considering what she’d just handed me.

Every year since then, I open the boxes as they come down from the attic and search for the doves. They are the first to go on the tree. Sometimes you don’t even notice them, nestled in the branches, but I know they’re there. On quiet evenings when it’s just me at home with a good book, I’ll sit by the tree and admire the twinkling lights and ornaments. When I see the doves perched in the tree, of course I always think of mom, her talent and creativity. But I also think of Mrs. Edlin. I’d like her to know I’m paying it forward. I try each year to give spontaneously and unselfishly, often to someone I hardly know. I’ve heard a lot lately that you never know how some small thing you do might be a giant thing in someone else’s life. The thing is that I know that very well. Once upon a time my Christmas miracle was two turtle doves.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Nov 30, 2014 | Thoughts

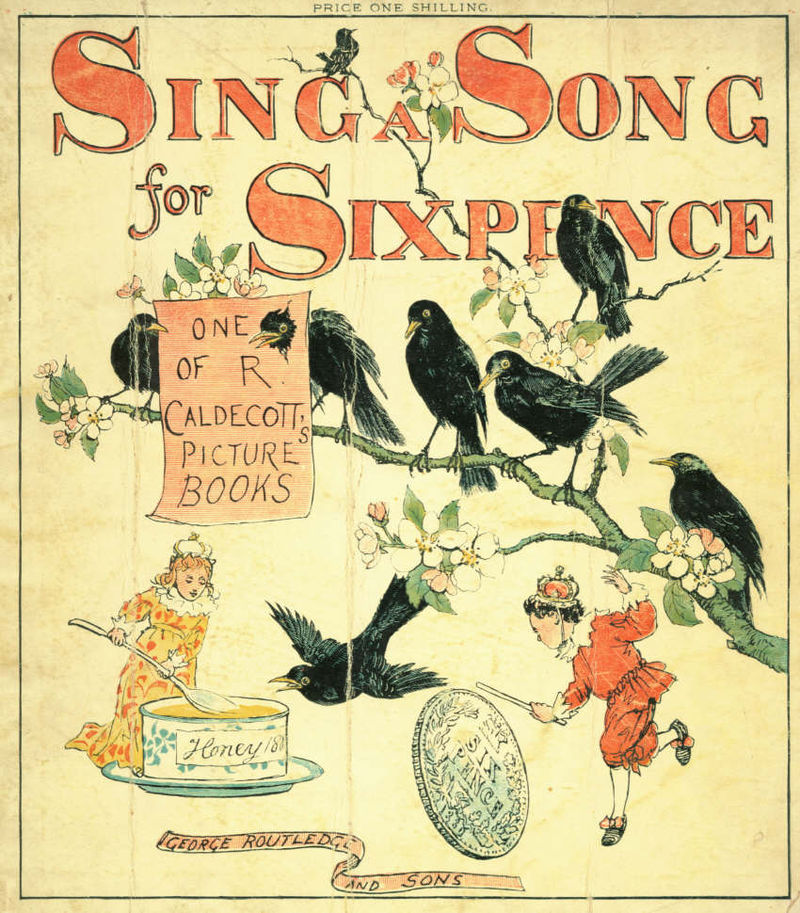

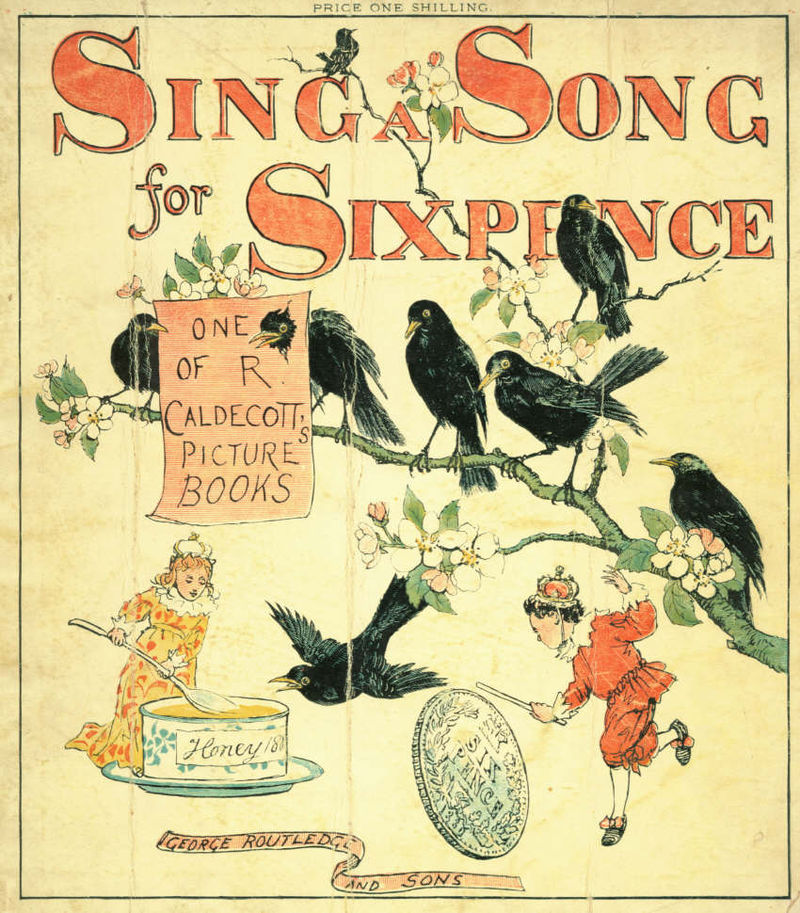

During our Thanksgiving meal this year, huge flocks of black birds rose and fell in a choreographed, synchronized dance in the field outside our window. It’s that time of year here. They are migrating south, stopping for respite in bare cornfields along their route. If you’re driving, you can see the power lines drooping with the weight of them, looking like musical notes penned in the sky. Trees bare of leaves appear full again, until with some secret signal the hundreds of birds posing as foliage fly away as one, de-leafing the tree in one fluid movement.

We remembered the old nursery rhyme, Sing a Song of Sixpence, where four and twenty blackbirds were baked into a pie that apparently was good enough for the king. My daughter, the picky one, predictably wrinkled her nose and declared she wouldn’t eat that. I just smiled to myself. There was a time when I would have said the same thing. Heady with the audacity and arrogance of youth, I made lots of similar proclamations of things I would never do, wear, say, or eat. In time, my “crow pie” would be repeatedly served to me steaming and piping hot, beaks bursting from the crust.

In my teens and twenties, the world was my orchard, fruit ripe on the tree ready for my haughty hands to deign to pluck it. We were a large, middle class family, and I never wanted for anything, really. The fact that in junior high, my mother wouldn’t buy me a pair of Jordache jeans that cost more than our week’s worth of groceries I chalked up to her stubbornness and lack of fashion rather than any financial reality. I took lessons at the local rec center: baton twirling, horseback riding. If I could’ve combined the two, I probably would have tried because why not? Couldn’t the world use more sequined girls twirling batons on horseback?

But, the best laid plans of mice and men, as Robert Burns says, oft go awry. I once had a showdown with my high school physics teacher as I dropped his class in favor of an English class more to my liking and abilities. “I’ll never use this stuff!” I told him. My first job out of college: science writing. Then, I got married and so many of the things I said I’d never do seemed to be swept down the aisle as fast as my white heels could traipse. I’ll never iron a man’s shirt; he’s got two hands. When you’re home for the day and he’s rushing out the door to make an appointment at work, how mean spirited would it be to just sit with your judgemental cup of coffee, declaring “you should’ve thought of that yesterday”? The compromise and give-and-take of married life was something I’d never imagined at seventeen, or twenty-two, or even sometimes now in my mid-forties. “I’ll never,” “I won’t,” “That’s not my problem,” are statements of petty selfishness that do no one any good.

Then came children and all bets were off. I’d never go a day without a shower and being presentable. Big mouthful on that one. I’d never let my child scream like that in a restaurant/airplane/grocery store/church service, etc. I’d never sit my kid in front of the TV so I could have a moment of mental sanity. Chomp. I’d never let my child walk around without shoes/pants/diaper/tissue applied to nose/scrubbed cherub cheeks at all times. Crunch. I’d never drive a minivan. Open the hangar, here comes the airplane. I was always going to be put-together, classy, with well-behaved, polite, scrubbed children. How hard could it be? Did Jackie O. ever have to catch a child’s vomit in her bare hands? Did Grace Kelly ever open her palm for someone’s chewed gum?

I’d be modest and in control at all times. During my firstborn’s birth, I vomited repeatedly and didn’t care who was in the room. “Students? Bring your friends, just get this baby OUT.” I’d always have the same metabolism I had at twenty-three and would never “let myself go.” I see now it’s not a deliberate “letting go” at all. It’s more of a desperate plea: “Wait! Don’t leave me!” I had a mammogram a couple of years ago, and the tech said something that never gives you warm fuzzies at your annual exam: “Well,that’s weird.” She invited me to come behind the monitor and look at the picture that had somehow appeared on her screen upside-down. For a second, I was elated. “That’s the perkiest the girls have looked in about 15 years!” I said. From then on, I always request my mammograms be viewed that way. It just makes me feel better.

I would always have cute shoes. Well, heels are just out. Don’t even bring them in my house any more because I can’t wear them without being crippled within 30 minutes. The word of the day is comfort, ladies. I can work with that, except for some days when I apparently can’t manage to pay attention long enough to put them on so that I leave the house with a different shoe on each foot.

After looking at old photos of my mother-in-law, I once remarked to her that I would never dye my hair. It was just so fake and not who you really were. (I know. Can you believe? If I were her, I would’ve broken up with me then and there.) My mother was prematurely gray in her 20’s. I was totally asking for it. So, between you, me, and my hairdresser, I’ve had two or three entire pies for that one.

It took a long time (I’m a slow learner), but I’ve stopped making blanket declarations. Learning this is a lot like making bread. You add things to the dough a little at a time, folding in the ingredients and kneading them together gently but firmly, letting the dough get used to the new bits. You sit it aside and give it time to rest and rise. And, if you’ve done it right, when it comes out of the oven lovely and browned, the product is much, much better than what you started with. Something worth sharing with others, even.

Over the next forty years if I’m blessed to have that many more, I hope I’m a lot more gracious, a lot less judgy. I’m racking my brain for things I’ve said I’ll never do when I get old and trying to take them all back. Plastic surgery? I’m game! Cruise ship to the Netherlands? Sign me up! Babysit for large numbers of grandchildren at once…..well, ok.

I want to be flexible, open, teachable. The more you know, the more you know how much you don’t know. I’m sure there are things I know for certain right now that will only be rendered laughable in a decade or two. So, be patient with me. And save me a piece of that blackbird pie.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Nov 4, 2014 | Thoughts

first communion, 1st grade

One of my great uncles had 11 children. They came to our house once, some of them having to sleep in our camper out in the driveway. At our house, when one of the five of us deserved a scolding, my mother tended to run all our names together as she yelled, too distracted to zero in on the one who was at fault. I tried to imagine what it must be like to mentally juggle 11 kids, so I asked my uncle what his kids’ names were. He got all the way to 10–twice–and could not for the life of him recall who he was leaving out. This both shocked and amused me.

In my Catholic childhood, big families were part of the scenery, as were loud, over-the-top wedding receptions, midnight mass on Christmas Eve, and sweating nervously in the confessional box. I went to parochial school for several years and wore a white blouse and blue plaid skirt with loafers every day as the nuns taught class. On a couple of occasions, I had to hold out my palm to be whacked with a ruler for talking too much. I can recite the Hail Mary, Our Father, and Grace Before Meals in my sleep. We went to mass with my father on Sundays, but my mother did not go. She had a falling out with the Church before I came along, and she spent Sunday mornings with her coffee and the crossword puzzle. I always missed her presence there, wished I could have heard her voice blending with my father’s in song.

I’ve always been a questioner. This did not always work in my favor (hence, the palm whacking). In third grade, the nun asked the class to close our eyes tightly and tell her what we saw. I said I saw blackness with bursts of flashing lights. (Try it–tell me I’m wrong.) Apparently, the correct answer was “nothing,” but I would not give in to that fiction. I knew what I’d seen and, like young George Washington, would not tell a lie. Lesson: people in positions of authority could tell you what you should believe, but they could not make you believe it. From then on, I questioned lots of things, which finally culminated in a hostile car ride on the way to mass one Sunday, when I demanded to know why I had to go. My father, at his wit’s end with my incessant questioning, gave up, pulled over, and told me I could walk back home if I couldn’t bear to endure a mere hour with God.

I stalked back home to my mother and the crossword puzzle, but he’d missed the point. It wasn’t God I was questioning. Him, I got. For me, God was personal and experienced. He was my Aibileen Clark, from The Help, whispering to me that I was kind, smart, and important, when everything else in middle school seemed to say the opposite. It was logical and reasonable to me that God was holding the world together. It was either that or Bermuda grass–an easy choice. It was the particular trappings of church I had trouble with. We read from the hymnal each week, with prescribed scriptures and songs according to what day it was. We sat, stood, and knelt as dictated. The “smells and bells” of the church were beginning to wear thin.

For the next few years, I read, studied, investigated, asked. At my father’s request, I had a Q&A with my priest, took lots of classes in college. The world of faith was a petri dish that I gazed at intently, curious to see what would appear, certain that something would. I found a more grounded, personal, rubber-meets-the-road faith in the Protestant tradition where I landed. It seemed more engaging, challenging, and best of all, encouraged questions. I watched and experienced a dynamic, alive faith in the lives of people I knew. So now I guess I have a sort of dual citizenship. When you’re raised Catholic, it’s something you carry with you, even if you’ve lapsed. It’s like being German by birth, but not walking around in lederhosen carrying a stein of beer. No one would even know by looking at you.

This past summer our family toured Israel, historically holy ground for three major world religions. There, you literally wear your faith on your sleeve. You can tell by hairstyles, dress, and language which faith someone holds, unlike in America, where we tend to hide it well. At the wailing wall, amidst dozens of orthodox Jews praying and chanting with a fervent rocking motion, I experienced a presence of the sacred so moving I wept. Walking in the historical steps of Christ, in the stone holding cells beneath the chief priest’s house, again there was a sacred awe. People at several of the Muslim sites we visited were openly hostile. There, I felt the opposite of peace, yet it was still a spiritual experience. Israel is an intensified microcosm of faith displayed in a bell jar for the world to see on the nightly news.

Despite how culturally adversarial and balkanized different faiths can be, tradition can be a useful talisman, a beacon shining on the path behind and lighting the way forward. Revisiting the church of my youth, I can appreciate a depth that I was oblivious to as a kid, squirming in the pew, and more importantly, I appreciate that others find a depth and a comfort there. I hope I have matured in many ways since that long walk home when I was banished from the car. One thing I have noticed is that much of my walk in faith has been like that moment in third grade—bursts of light in the blackness. Moments where I totally get it and feel a grateful peace, and moments where I stumble along in the dark stepping on Legos, ignoring lights along the way. I still question, seek, occasionally doubt or wonder, and encourage my kids to do the same. It warms my soul that they can hear their dad and me blending our voices in the pew on Sundays, not because we make some lyrical harmony, but because we are creating a tradition and a beacon of our own, one they can draw a peace from and build on themselves. I am grateful they know a personal Father who will always, no matter the chaos or multitudes, be able to recall their names, leaving no one out.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Oct 20, 2014 | Thoughts

Halloween was not always such a big production. Thirty years ago, it came down to a mad scramble once it got dark after dinner on October 31. Suddenly, it would occur to us that we could go out and beg for candy. In typical last-minute fashion, my brother and I would appeal to my mother’s creativity, which no doubt would be lagging by that time of day. She would dig through the hall closet, perhaps find a hand-me-down costume one (or all) of our sisters had worn in years past, and that would be that.

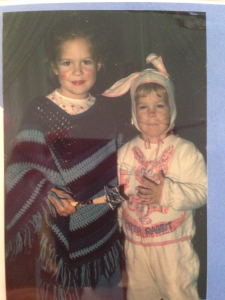

1973, my brother and me

I remember the year I declared I wanted to be a princess. She looked me up and down, thought for a minute, and pulled a blue handmade knitted poncho over my head, cause nothing says “princess” like knitted evening wear. She fashioned a star out of aluminum foil and stuck it on the end of a wooden spoon that she’d yanked out of a kitchen drawer. A couple of bright red spots of blush on my cheeks and voila: princess! For some reason, I was satisfied with this. It was all in the attitude. If the tiara fits, right? My brother and I were each handed a limp pillowcase for candy, got pats on the head, and off we went into the dark neighborhood.

Some years ago, my family was invited to a Halloween event where we were supposed to show up in coordinated costumes. As the Family Organizer, I decided we would go as The Incredibles. It was one of our favorite movies. My husband is even named Bob, like the main character. Our kids fit the ages perfectly. I scoured the internet for deals on costumes. Have you priced Disney costumes lately? They’re no poncho-and-foil-star get ups. But, it was important that we look impressive. We might even win a contest, for crying out loud. I shelled out some significant cash, informed the family what we were going to be, and waited for the night of the party.

Son was ready to go early. He loved the idea of being Dash, the fastest boy in the world. We spiked his hair, donned the gloves and boots, and I sent him out to the front yard to practice sprints. I slipped into Mrs. Incredible easily enough, opting for black boots from my closet instead of the ones that came with the costume. It was a little short in the torso, and a bit choky at the neck, but I was willing to take one for the team. It was getting close to time to go, and our daughter hadn’t appeared yet. She finally came out with a glowering look and her arms folded sulkily. The back of the suit was totally unzipped. “This doesn’t fit. I’m NOT wearing it.” In fairness, I’d ordered the costumes a couple of months early, so it was possible she’d grown some. I tried zipping it up. “It’s choking me!!” she yelled, clawing at the neck. “This is SO lame.” I ordered her to change her attitude and go upstairs to finish getting dressed. She wouldn’t have to zip it up the whole time. She could just do it when we got there and then wear a jacket over it to cover up the open back so she could breathe later. Honestly. Breathing was seriously an issue? These were coordinated costumes, people!

It was almost time to leave. Son (Dash) was waiting in the car. I yelled upstairs for everyone to mobilize. Daughter (Violet) came stomping down, each step an audible Attitude in Motion. She was dressed in jeans, a parka, and tall, fuzzy boots. Seeing my expression, she proclaimed, “I’m just going to be an Eskimo. Everyone ELSE can be the Incredibles.” That’s when I lost it. “Get back upstairs and GET YOUR COSTUME ON! We are GOING as a FAMILY and we are GOING as the Incredibles. IT. WILL. BE. FUN.” She retreated, peeling off the parka as she went.

About that time, in classic introvert form, Bob decided he would rather just stay home and read. “Not this time!” I declared. “We are going as a family.” I must have lapsed into a Halloween-ish raspy growl because he set the book down and headed for the bedroom. The man never does anything in a hurry. “We are going to be LATE.” I noted, which usually only served to make him go slower. After five minutes, I stuck my head in. “Ready? Wait. What is wrong with your suit?” He had pulled it on, but absolutely refused to wear it without something underneath. The suit strained at the seams, as he’d pulled it over his jeans, complete with his overly-stuffed wallet in the back pocket. It bulged and poofed in all the wrong places, looking not so much like the muscles of Mr. Incredible as some odd tumorous affliction of his extremities. “Oh, for heaven’s sake.” I said. No way were the costume’s boots going to fit over his white socks and tennis shoes (he wears a size 12 shoe). “What?” he groused, “It looks fine.”

I rolled my eyes and gritted my teeth, just trying to make it out the door to our fun-filled family-centered event without the words in my head actually making it past my lips. Our teenage daughter tromped out the door, the back of her suit wide open, giving me the big hairy eyeball. Bob folded himself and his bulging muscles into the passenger seat, and we took off for the party. Once we arrived, we put on our masks (matching, of course), and posed for the family picture that showed, for all anyone knew, a creative and happy crew. We’d done it! We were The Incredibles! Our daughter played the part of Violet perfectly, people assuming her sulky, dour face was part of her role and not a result of a lack of oxygen and irritation at her mother for making her wear a too-small costume. She played it so well, she actually won an award for Best Youth Girl Costume. (oh, the irony!)

After the picture, Bob changed in the car. It was pretty easy, since his entire outfit was already on underneath his suit. Violet peeled off her suit and put the jeans and fuzzy boots back on. So that was what was in the bag she’d carried out with her. After about 30 minutes, I took off my boots, which were starting to pinch. Dash was the only one who was still in character by the end of the night.

Next time, I’m heading for the hall closet, and we can be a family of hobos.

the Incredibles!

by bsquared5@aol.com | Oct 13, 2014 | Thoughts

I’m a transplant. Growing up as an Air Force brat meant my family uprooted every couple of years and moved to a new place. New schools, new friends, new geography. Although I was born in Japan, we stayed only 6 weeks after my arrival before pulling up stakes for Virginia. (I should tattoo “Made in Japan” on the bottom of my foot just to prove I was there.) After that, it was Florida, South Carolina, then Florida again before finally landing in Tennessee for high school upon my father’s retirement.

Starting high school in the small-town South was cultural whiplash. As the new kid, I talked “funny” (too fast, no accent), didn’t get local references (turn left where the old hospital used to be–huh?), and found it really hard to make friends with people who’d not only known each other since kindergarten but had a good chance of being related to each other. Enter my new best friend: the only other person in the county who’d moved in from Elsewhere. She commiserated with me when we couldn’t understand the lingo (what the heck was a hosepipe and why was it ruint?) and reminded me I wasn’t weird just because I “wasn’t from around here.”

Maybe it was this scratchy-wool-sweater discomfort that gave me a restless urge to wander. Or it could be that just after my parents finally got all five of us out of the house and on our own, they bought a camper intending to travel and explore together. Not a year later, my mother had passed away from cancer and the camper sat unused and vacant in the driveway. Once I was married with two children, the unquenchable wanderlust descended with a vengeance. I remembered my own rambling childhood, exposed to different people in different places, and I wanted my children to experience the same, to embrace the new kids that moved in and to find other people interesting and worth knowing.

As soon as our youngest was out of diapers, we took off for the West Coast and the Golden Gate Bridge. We had to wait til then because I have an innate fear of traveling with very small children. My mother had told me repeatedly how I had screamed and wailed in her arms for the entire flight from Japan to the US. She recounted the feeling she had that the resentful passengers who glared at her were plotting to throw her off the plane, midair. I would just be asking for karmic payback if I tried to travel with an infant (sorry, Mom). Our children, then 6 and 3, did great–fate was kind to me. We began to deliberately pay our business pharmacy bills with credit cards in order to rack up air miles. Since Tennessee is fairly centrally located (it borders 8 other states), we took long weekends and holidays and drove to nearby states to explore.

It didn’t take long to realize we had actually been to quite a few states, mostly in the Southeast. We decided to set a family goal to visit all 50 before the kids left for college. That gave us 10 years from the time we started to reach our goal. We tacked up a big map of the US in my son’s room and began sticking pushpins into each new state we visited. We got creative, taking an Amtrak sleeper train from Atlanta to D.C. once. Family and friends became waypoints. We visited family in Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Florida. We saw friends in Minnesota, Delaware, New York, New Jersey, and Mississippi.

As the kids got older, our travels usually included something educational. We followed the Freedom Trail in Boston, explored the cliff dwellings of tribes in New Mexico, toured Frank Lloyd Wright homes and learned about architecture, and saw the 9/11 memorials in Pennsylvania and New York. Long, tedious car trips transformed into an appreciation for the incredible varied landscapes of America. Our country truly is America the Beautiful: coastlines, mountains, deserts, lakes, plains, powerful cities and sleepy country towns. We touched anemones in Oregon tidepools, marveled as Hawaiian lava ran into the ocean, and outran sudden prairie hailstorms in South Dakota. Our nation’s national parks never failed to delight. We hiked through Bryce and Zion in Utah, the Grand Canyon in Arizona, Yellowstone in Wyoming, Denali in Alaska, and the Smokies in Tennessee.

Along the way, whether it was Route 66 or US-1, we sampled clam chowder, fresh beef, and once, quesadillas made from Cheese Whiz that made us laugh until we cried because they were so terrible. Our kids were intrepid travelers, expert packers. It became second nature to navigate airports and hotels, to find their way with a map in a new city. They witnessed how to handle mishaps on the way–we once broke down in the middle of the Mackinaw Bridge in Michigan–and they filed away memories. Unexpectedly, I found that there’s a comfort in having a home base. Having been raised with shallow roots, it’s been a pleasant surprise to actually sink deep in one spot and nestle in. Each time we returned home from a trek to Elsewhere, it was good to hear the familiar cadence of people’s speech (slow, with an accent) and to know that I actually know where my town’s old hospital used to be.

Two years ago, we reached our goal, checking off the last state when we crossed into North Dakota. We had a celebration in the middle of nowhere, the only witnesses a couple of cows and a cloud of black flies. We snapped a picture by the “Welcome to North Dakota” sign, and I gave a private, silent high-five to my mom, who would’ve liked to have seen North Dakota (despite the flies).

by bsquared5@aol.com | Sep 22, 2014 | Thoughts

my bendy giraffe daughter

my bendy giraffe daughter

The outcome of genetics freaks me out a little. One morning while waiting for the bus, I eyed my sister as she laughed and chatted with her way-cooler high school friends. I was just in the third grade and with my pin straight hair, blue plaid skirt and knee socks, was miles apart on the popularity spectrum. I watched as they formed a circle around her, and then I heard shouts of amazement: “No way!” “Gross!” “How do you do that?” As I edged close to the circle, I saw why they were yelling and laughing. She had done the Arm Thing.

I don’t know what made me do it. I cut through an opening in the circle and proclaimed, “I can do it, too!” She rolled her eyes at me and looked around at her friends, as if to say, “Can you believe this irritating pest?” “You can not!” she snorted, and that was all the prodding I needed. I threw my backpack on the ground, planted my loafers on the asphalt and clasped my hands behind my back. Leaning slightly forwards, I bent my right elbow backwards at a sickening angle and in a fluid yet grotesque movement, twisted my shoulders impossibly until my clasped hands came forward and rested in front of me. I lifted my chin in triumph, her friends thought I was cool for about two minutes, and then the bus came.

I had witnessed her do the Arm Thing before and somehow just knew I could do it. It became my signature show-off move, better even than touching my tongue to my nose. I bragged that if I was ever arrested, I would be able to get out of the handcuffs. Once people had seen me do it, they’d ask me to show their friends: “Watch this!” they’d say, “Come on, do your Arm Thing!” I did it through high school and college by request. At a college retreat as a college sophomore, I won a Stupid Human Trick contest with the talent. Turns out, my younger brother was able to do it, too, the irritating little pest, and he often upstaged me since he was a smaller, cuter version of me.

We were double jointed in the elbows and shoulders, I learned. If I leaned my hands on someone’s desk, my elbows would hyper-extend and look like they’d been put on backwards. It came from my dad and his aggressive genetics. We got his nose, his feet, his warped sense of humor, and apparently his build. I’d never seen him do the Arm Thing, but as a teenager he was built like all of us–thin, gangly, a bit clumsy. This came from his mother. In her 70’s she would scrub her entire kitchen floor by hand, folded in two at the waist, her legs straight, her torso bobbing slightly as she worked. We were bendy. Had we thought about it, we could’ve developed it more and joined one of those Chinese acrobatic troupes as the Amazing American Trio. I have no idea how my sister initially figured out she could do this. At some point, maybe she had escaped the back of a police car? (Hmmm…I will need to investigate this further…).

At least one of my sister’s kids and both of mine have inherited this ability. They heard me talk about it once and, like me, just knew they could do it too. I never asked them to try it and certainly don’t encourage it. Age has changed my doubled joints, alas. The last time I attempted the stunt, I heard so many crackles and pops as my arms passed my ears that I declared it the end of the Arm Thing. Let’s just hope I don’t get arrested any time soon. I’d be shuttled off to the Big House with no hope of escape.

We could have won the genetic jackpot and gotten genius musical talent, a natural immunity to the common cold, or a killer metabolism that kicked in at middle age. But no. We got the Arm Thing to amuse and entertain others. Maybe it was a small gesture to help us through some awkward childhood moments. Unless some more aggressive genetics invade our gene pool down the line, it looks like it’s a hand-me-down that’ll be there through a few more generations. As for me, the Arm Thing is just a stunt from my past. I can still wiggle my ears and touch my tongue to my nose, but the Cool Factor is just not there. I’ll need to find another way inside the circle. :/

The best Christmas gift I ever received wasn’t a Christmas gift at all, but a spontaneous, compassionate gesture from a friend of a friend. When I was a kid, if you came running into the house all hot and sweaty from playing outside in the Florida heat, it was a good bet you could find my mom in front of her sewing machine, probably with some Anne Murray playing on the stereo.

The best Christmas gift I ever received wasn’t a Christmas gift at all, but a spontaneous, compassionate gesture from a friend of a friend. When I was a kid, if you came running into the house all hot and sweaty from playing outside in the Florida heat, it was a good bet you could find my mom in front of her sewing machine, probably with some Anne Murray playing on the stereo.