by bsquared5@aol.com | Jun 29, 2016 | Thoughts

If you don’t count song lyrics, I have a short list of things I’ve learned by heart: the 23rd Psalm, a brief poem from my childhood, the Preamble to the Constitution, and Antony’s soliloquy from Julius Caesar. Oh, and the Pledge of Allegiance. Because ‘Merica.

Ancient Greeks used to believe the heart was the seat of intelligence, emotion, and memory. In some ways, that may be true. In many cases, people who have had heart transplants report having at least temporary memories of things that happened to the donor.

This week, we are celebrating our 25th anniversary, and while we may not have exchanged hearts in a literal sense, we do share decades of memories. If such a thing can be true of people and not just poems and pledges, I know him by heart. The date of our ceremony is engraved on the rings we wear, but we started learning about each other about 7 years before that, essentially growing up together since meeting in high school.

On a stifling hot June afternoon, we got married under a canopy of trees in a state park across the street from my parents’ house. After the promises and shy public kiss, we walked hand-in-hand down the aisle to the Beatles singing “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?”. I was barely 22. He was in the middle of vet school. He had hair. I had a waistline.

On a stifling hot June afternoon, we got married under a canopy of trees in a state park across the street from my parents’ house. After the promises and shy public kiss, we walked hand-in-hand down the aisle to the Beatles singing “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?”. I was barely 22. He was in the middle of vet school. He had hair. I had a waistline.

We had exactly one fabulous week at the beach, where we both got alarmingly sunburned and had to drive 10 hours home trying not to let our skin touch the seats of the car. Good times.

Cue the sound of crashing expectations. Those first years were sweet, but tough. Tuition and car insurance led to cereal for dinner occasionally. Late nights studying for vet school made for lonely channel surfing instead of foot rubs and cuddles. Stress from work came home with me. We fought. Sometimes badly. This was a far cry from hours of sharing dreams and giggles on the phone at night and going out on dates each week. Now we shared finances, family, furniture. Everything, it seemed, had to be negotiated, compromised.

Eventually, we leaned in. His infinite patience and our shared sense of humor buoyed us. That, and the fact that we treated the union as a third party, something separate from ourselves that needed care and attention. Looking at our wedding photo back when we were fresh and doe-eyed, if I could have shared some wisdom with the Young Us, it might include the following.

- Congratulations! You are now a complete family. Notice children have nothing to do with this, so when people ask you when you plan to start a family, tell them you’ve already checked that off. If later on you feel the need to procreate, rock on. But you’ll just be expanding the family you’ve already made. When the kids leave home, I still got you, babe.

- Your spouse cannot and should not fill all your needs or empty spaces. While you might make a great team and complement each other in all the right places, you still need friends, interests, and soul-filling that have nothing to do with one another. (Ditto for children, by the way.) It’s not in the marriage job description for him or her to make you happy.

- Have a focus outside yourselves that you can look outward toward together. I’m not talking about a weekly trip to Home Depot for the latest DIY project. I mean a common service to your community/world at large, so you can remember that there’s a whole lot going on outside your little bubble of two. Pray together.

- Learn how to fight. Even if you can’t imagine a cross word in your lovey-dovey state of bliss, it will come, and arguments shouldn’t shake your whole foundation. You’ll disagree about something–in-laws, money, sex, division of labor, children, or asinine stuff like rinsing out the cereal bowl or peeing with the door open–and if you know each other’s battle mode and can see beyond the conflict, the casualties are fewer.

- Assume the best. Beyond the morning breath, snoring, hair in the drain, and the way she sings off-key is the person you chose for better or worse. Remember their best self. Don’t see them as they really are, see them as their best version–Spouse 2.0– and stockpile your grace. Hope like crazy they’re doing the same for you. You like someone because. You love someone although.

- If you got married for safety or security, it’s too late for a refund. You should’ve read the fine print. Love is not safe. Human love is never pure or perfect. It comes with truckloads of imperfection. Love like this is the biggest risk out there. If life is kind and nobody gets hit by a bus, the payoff is golden. You get to be those adorable old people that everybody envies walking hand-in-hand in the park. You’ll hold up your hair and he’ll automatically zip up the back of your dress. You’ll straighten his tie and admire how good he looks in a suit.

- Being a person is hard sometimes. When you lose a job, or a parent, or a child, or if there are surgeries and procedures and prognoses involved, hang on. Love is not the honeymoon at the beach. Love is the roof sailing through the wind in the tornado, and the two of you huddling together in the closet, not letting go. Be each other’s weight-bearing wall.

- Find other people who are doing it right and copy them. Don’t make it harder by trying to do it all by yourselves. Ask for help if you need it. Sometimes an objective voice is critical.

- Forgive. Forgive lots of times, and then forgive some more. Kindness goes a long way. Speak life to each other. The world is hard. Be each other’s safe place.

So, the Preamble, Psalm 23, a poem, a bit from Shakespeare, and Bob. The things I know by heart. Happy Silver.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jun 28, 2016 | Thoughts

**This post originally appeared as a guest post on The Eternal Scribbler.**

Anyone who has ever wanted “to be a writer” knows that putting coherent thoughts on a page can be a challenge. So many elements vie for a writer’s attention: setting, plot, word choice, character, dialogue. Trying to tame these wild things into submission sometimes feels like a frenzied game of Whack-a-Mole, flailing away in a sweat ending only with the writer needing a stiff drink and the mole hobbling about with painful bruises.

On any given day, writers tend to waver alarmingly between feeling god-like and feeling like something scraped off the bottom of a pig farmer’s boot. One minute, characters and ideas spring like gazelles from their imaginations, and they spin gripping tales of romance and danger they can’t wait to share with the world—or at least that one friend who only says nice things. In the space of an hour, their mood shifts–now dialogue reads like it’s been recorded by the minivan navigation system and all the characters are dull cretins who move stiffly through the plot like hand puppets.

The difference between the first—(the artist)—and the second—(the hack)—lies in writing invisibly. Many years ago, pushed by a looming deadline in a graduate class, I wrote the following story, hoping to at least win some humor points with my professor. This is one version of “invisible writing.” Bonus: it takes less than a minute to read.

The Invisible Story

Once , prince princess.

marry, but

evil dragon. ?

“No!”

“ , my love.”

many tears.

land far away, .

, . !

Instead, her. “ !”

roaring, gnashing, flaming .

scales . Sir .

princess. , thrusting his sword, .

, ! last gasp,

shattered armor . roar,

triumphed, eating . grisly .

died of grief

from her tower.

Moral:

While the moral of this story is left to the reader’s imagination, you easily garner the main idea with just fragments and punctuation. The thing is, it takes very little to convey an entire plot. The skeleton of a story, if it has strong bones and especially if it’s a universal tale or truth that resonates, can ably stand without much interference from an egotistical writer.

Writing that appears effortless tends to occur when the writer gets out of the way of the characters and their goals. The writer is present, of course. The story and voice are hers, but she doesn’t leave grubby fingerprints all over the pages, which is distracting at best and annoying at worst. Rather than keeping a white-knuckled grip on the wheel, a good writer lets the story steer itself for the most part, with only the slightest corrections here and there. I love that the earliest writing tools were quill pens topped with feathers, a visual reminder to have a light touch.

How do you write invisibly, less heavy handedly? There’s no need to be as cheeky as my example.

- Know the tools. Grammar, spelling, punctuation, sentence construction. Read anything by William Zinsser or go back to your high school Harbrace for the basics. This should go without saying, but here I am saying it. Leaving errors littered through your writing is leaving a trail of breadcrumbs straight to the writer rather than allowing the reader to focus on the story and is anything but subtle.

- Write YOUR story. This does not mean that if you have never touched a dragon, you can’t possibly write about them. Imagination is allowed! It simply means that the truest (most invisible/effortless) writing that will resonate most with others is that bit of yourself that has been scarred, deliriously happy, or terrified. Draw upon that instead of manufacturing fake tears—the reader can tell. Everyone has her own story. Even if everyone has been to a sixth grade dance, not everyone has been YOU going to YOUR sixth grade dance.

- Pay attention to language. If you don’t have a somewhat freakish fetish about words, back away slowly from the page. Writers should at least feign interest in the words they enlist. Otherwise, the workers may just rise up in mutiny. Thesauruses are useful, but use real, recognizable words. Don’t use a fifty-cent word when a nickel word will do. Don’t insult the reader’s intelligence by explaining everything in excruciating detail. Some writers are like those people who shout rudely at foreigners, thinking they’ll be understood better if they just increase their volume. Finally, use profanity sparingly. As my mother used to say, it shows a lack of imagination.

- Practice. Lots. It takes at least 10,000 hours to be any good at anything, so you may as well get comfortable. In the course of practicing, in which you will write choppy, painful sentences and incoherent drivel, you will eventually learn to sift the chaff from the wheat and begin to duplicate the parts that flow, have a rhythm, and ring true—in other words, parts where you were invisible and the story shone through.

- Imitate. (see #3). In your love affair with words, you will need to read prolifically, maniacally even. Read widely and outside your preference and culture. Read poetry, screenplays, non-fiction, and novels. Reading will do two things: it will increase your vocabulary and it will train you to recognize beautiful craft. At some point, you will be casually reading a paragraph or a sentence, when you will be struck by its perfection. Not only has the writer nailed a feeling or situation so exactly, but he will have done it with words that read like poetry, where your only response is to pause, savoring it and staring into space at the deliciousness of it, the book held limply in your lap. That is what all writers aim for. Find your writing heroes and reverse engineer them. Let them influence your thinking, which will influence your writing.

You will still have those distracted Whack-A-Mole days that leave you exhausted from the wrestling match, but try to tiptoe more than you stomp through your pages. Your readers will appreciate being beckoned softly along by the voice of the invisible writer.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jun 28, 2016 | Thoughts

Marks & Co., London

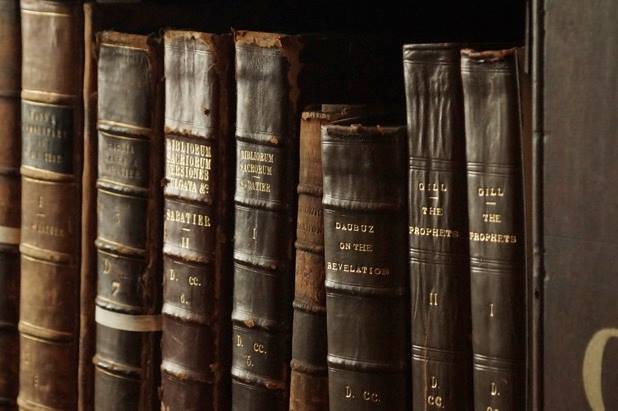

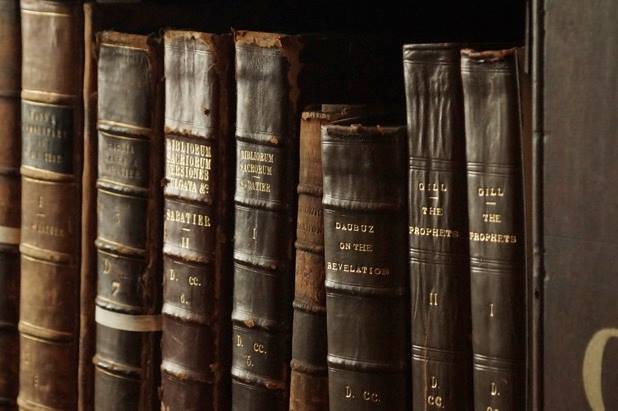

Years ago, I stumbled across Helene Hanff’s 84, Charing Cross Road, a record of the correspondence between Helene, a snarky Manhattan writer, and Frank Doel, acquirer of rare editions at an antiquarian bookstore named Marks & Co., in England. I fell instantly in love: with Frank, Helene, and the dusty, jumbled bookstore, itself a tangible character in the story. The tale was later turned into a play and then a movie, starring Anne Bancroft and Anthony Hopkins, which is perfect to watch on a gray winter afternoon, under a cozy blanket with chocolate and coffee–and a cat or two.

Bookstores like that one, or the fictional Flourish and Blotts shop in the Harry Potter series, are now too often the settings in novels rather than addresses on a real map. I prefer old-school books with creaky spines and pages marked with notes in the margins over the shiny, precise Kindles and Nooks with pages that turn with an elegant swipe rather than a lick of the finger and a leftward toss. New is popular. Bookstores now have less tolerance for lingering over leathery used volumes. Covers must be eye-catching and colorful, the newest and freshest within a few steps of the entrance. After a few short weeks, the shelves are swept clean and their contents tossed onto the “clearance” pile, to make way for the even-newer to serve the waning attention span of the modern American.

The lure of the corner book store is irresistible. Whether it’s a cookie cutter chain store or a mysteries-only shop with a resident cat languidly posed across the Dick Francis shelf, the smell of print-on-page and the potential of all those uncracked spines is a siren’s call of temptation for people like me. The best bookstores have managed to maintain an atmosphere that caters to lovers of books, without too much peripheral merchandising. I’ve been in a few that I’d consider national treasures.

There’s the Tattered Cover in Denver, an enormous indie bookstore open for over 40 years. It has overstuffed chairs that beckon you to stay and read a chapter or two of a new or used volume. I discovered this piece of heaven in college. Sadly, they refused to let me use it as my dorm room.

I wandered for hours through Powell’s in Portland, Oregon, which takes up a city block and has a charming children’s section.

In my neck of the woods, co-owned by bestselling author Ann Patchett and publishing veteran Karen Hayes, Parnassus is nestled in a small corner in a bustling area of Nashville. It’s an independent jewel of a bookstore that hosts a steady stream of author events for its community of book lovers. Adding to its charm and personality, you likely will be greeted by one of many of the store’s shop dogs.

A friend recommended The Strand Bookstore on the corner of 12th and Broad in Manhattan. On a rainy day visit, I dashed inside and browsed  clear through lunch, marveling at the rare titles and unique categories in the eclectic atmosphere. Good thing I had a subway ride back to the hotel, which limited the number of bags I could reasonably carry with me.

clear through lunch, marveling at the rare titles and unique categories in the eclectic atmosphere. Good thing I had a subway ride back to the hotel, which limited the number of bags I could reasonably carry with me.

When we were first married, my husband and I haunted the famous Davis-Kidd Booksellers every weekend in Knoxville until it closed. It became our favorite date night. It was dangerously just down the street from our first apartment and it threatened to ruin us financially. Rent or books? Groceries or books? It’s not always as clear-cut as you might imagine!

The common denominator of these bookstore royalty is the personal connection they all strive for, whether they take up several stories on a city block, or they’re in a tight corner in an overlooked alleyway. It is so easy today to remain isolated, with books arriving at your doorstep via a credit card and mouse click. At bookstores like these, if you’re a regular, the staff knows your tastes and can recommend reads they know you’ll love. You can chat with other bibliophiles who rave about something they’ve just read because it’s just that good, not necessarily because it has the right ranking or the right reviewers. You can meet authors and tell them how their words changed you.

The antique booksellers at 84, Charing Cross Road have long gone, and the location has housed many things since; a wine shop, a restaurant, and currently a McDonald’s (blasphemy)! Fortunately, the truth of the story remains. The impact a simple bookstore and its gentle owners can have on a person runs deep, spanning decades and continents. In a letter to her friend in 1969, Helene wrote: “If you happen to pass by 84, Charing Cross Road, kiss it for me! I owe it that much.” I know the feeling.

Thanks for reading! To return to the FICTION WRITERS BLOG HOP on Julie Valerie’s website, click here: http://www.julievalerie.com/fiction-writers-blog-hop-june-2016

by bsquared5@aol.com | May 6, 2016 | Thoughts

At 24, I wrote my mother’s obituary. It wasn’t my first publication but it was certainly the most memorable. For a long time, her absence was the thing you needed to know first about me, if you were interested in knowing me at all. It drew jagged unreasonable outlines around my life, boundaries I couldn’t (or wouldn’t) cross, defining whom I could trust, what I might accomplish, and instilling in me a what-if mantra that drove me to compulsively record memories for my own children.

Mothers are the ground of all being, our primary source of food, comfort, and love. They’re somehow just there, on call to Nurture and Nudge: a given, like oxygen. It’s said that fish discover water last, which may be one reason moms labor unappreciated for so long, like underpaid set designers and lighting directors, working backstage to make our performances masterful. It’s only after we watch the movie premiere and get the Oscar that the brilliance and handiwork that made it all possible becomes clear. At 24, it was just starting to dawn on me that my mom had a history and was an interesting, funny person. I had questions and and still expected–needed–her guidance.

By then I had a master’s degree, a job, and a young marriage under my belt. I have friends who didn’t even get past grade school with their mothers still around, so I should’ve felt lucky. Lucky never occurred to me. Mostly I was Sad, which on most days walked around hand-in-hand with its cousin, Angry. Every time I went to pick up the phone to call her, a familiar sting rose in the back of my throat, quickly followed by a rush of irritation. Friends of mine talked casually about going shopping or grabbing a quick lunch with their moms and a cloud of resentment hovered overhead. Worse, people complained about their mothers being nosy, critical, or pushy, and it took all my strength to bite my tongue.

She died in October, so Christmas that year was a challenge, but I was wholly unprepared for what came six months later–Mother’s Day, the scourge of holidays for those with a membership in my particular club. Every drugstore, commercial, and print ad seemed to twist the dagger. My poor mother-in-law, who through no fault of her own could not replace the mother I’d lost, I’m sure felt my lack of enthusiasm. I had to sit through the Sunday sermon praising the virtues of mothers, which I endured only by repeatedly singing The Star Spangled Banner in my head.

Several years later, my own children came along and sweetened the day a bit, but there will always be a mom-shaped hole in the day. Mother’s Day can be excruciating for those who have struggled with infertility and long to hold the title of “mother” themselves. It’s perhaps worst of all for those who have lost a child and face those who tiptoe around the holiday unsure of what to say. Tip: honor their motherhood, however brief. Doing so honors the memory of their child as well.

When you’re not a raving fan of Mother’s Day, you can weather it with a tight smile and some quiet tears when it’s all over, kind of like the present political campaign. Or, you can focus on the other meaning of mother as a verb: to tend with care and affection. In my mother’s absence, sisters and close friends have stepped in to tend in just this way. Having offspring is not a prerequisite. It’s a reflection of the deepest impulse of human kindness and does not require small handprints in clay or dandelion bouquets.

It’s the time when a friend gave my son a ride home when I was impossibly late, and the time when I surprised my daughter’s friend with her favorite dessert for her birthday. It’s my friend who never fails, even after 20 years, to squeeze my shoulder, even through the phone, on days she knows will be tough. It’s my mother-in-law’s gift of an antique pitcher, the kind my mother used to collect. It’s bringing dinner to someone after surgery, helping decorate someone’s Christmas tree after a car accident, sending a text to a teen on their mom’s birthday, because she’s no longer here to celebrate–and you get it. Small kindnesses, stepping in, stepping up: all the things that mothers do in any given day.

Happy Mother’s Day to the Queens of quietly helping others when they need it. Happy Mother’s Day to all of you who are so great at mothering.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Apr 25, 2016 | Thoughts, Words

Recently, I ran across a video of children discovering their shadows for the first time. Their reactions range from fascination to uncertainty to outright fear. Imagine! Here you are minding your business on a bright, sunny day and suddenly a dark figure appears who (the audacity!) mimics your every move.

Once we grasp that our shadows aren’t out to get us, and assuming they’re not the rascally runaways like the shadow of the unfortunate Peter Pan, we learn how to manipulate them. A tree outside my childhood bedroom cast long shadows on the wall in the evenings. I’d form my hands into shadow puppets of birds, which flew about its branches, landing and taking off with dramatic flutters. A talented friend of ours made comical bunnies, menacing wolves, and cunning crocs come alive with just his hands and a spotlight.

A shadow is, after all, just a projection made from light. This mind-bending photo by  George Steinmetz shows an overhead image of shadows cast by a caravan of camels trekking across the desert sands. What earned this picture its status as one of 2005’s best photos of the year (National Geographic) is that if you look closely, you see the camels are actually the thin white lines. The dark recognizable camel shapes are all camel shadows. Whaaat?! Go ahead, enlarge it and see.

George Steinmetz shows an overhead image of shadows cast by a caravan of camels trekking across the desert sands. What earned this picture its status as one of 2005’s best photos of the year (National Geographic) is that if you look closely, you see the camels are actually the thin white lines. The dark recognizable camel shapes are all camel shadows. Whaaat?! Go ahead, enlarge it and see.

The light, directed just so, projects an image that creates a much greater impression than the object itself. Perspective is slippery. Had this photo been captured at a different time of day, the camel shadows would have instead been long wavy lines trailing behind the caravan. Nothing special. When the light is strongest and at its best for creating projections, it changes what we see of ourselves; it changes how we are seen by others.

The shadows we cast change over time, or maybe it’s that time changes the shadows we cast. In the morning of life, when we are unsure and unsteady, the strength of our shadow may frighten us, like the children in the video, and send us scurrying back into the comfort of shade. Later, conditioned by rejection, loss, or a shaky belief in who we are or what we can be, it’s much easier to stand in someone else’s shadow rather than risk casting our own. We don’t trust what the light might reveal, or perhaps we have our own idea what might be projected and we fear it’s more like a misshapen weasel than a swan.

Once upon a time, we might have been a child on a rocking horse or a wobbly duckling running for cover. A few along the way, parents, treasured teachers, a best friend, see us for who we are meant to be, who know what treasures lie within. They see us from above in the afternoon, and to them the rocking horse seems a galloping stallion, the duckling a darting hummingbird.

One day, we grow tall enough and brave enough to  stride into the day with confidence, casting our own shadows boldly and realize what we have been all along. Armed with grace, we see what our own two hands are capable of shaping onto the wall, when we let the light in.

stride into the day with confidence, casting our own shadows boldly and realize what we have been all along. Armed with grace, we see what our own two hands are capable of shaping onto the wall, when we let the light in.

Now, well into my fourth decade, I feel more comfortable in my own skin than at any other time I can remember. It feels good to stretch my muscles in the sunlight, and I find myself lingering to soak up its warmth. I’m more curious than afraid of what images its rays will scatter.

We, as a matter of course, extend this powerful light-wielding vision to our children, family, friends, and even strangers. Why is it we so often withhold it from ourselves and keep our shadow casting small and timid? Standing in the shade, we throw no shadow at all. Our canvases are empty. Afraid to be just ducklings, we never see the hummingbird’s gossamer wings flickering in the sun.

The truth is we are all a bit of both: ducklings and hummingbirds, camels and thin white lines. Each comes from the other; each is lovely and full of light. Don’t wait for permission, perfection, or “the right time.” Cast your shadow, big and bold.

Thanks for reading! To return to the FICTION WRITERS BLOG HOP on Julie Valerie’s website, click here: http://www.julievalerie.com/fiction-writers-blog-hop-apr-2016

by bsquared5@aol.com | Apr 6, 2016 | Thoughts

Back in another life, I flew without wings. All my free time was on the back of a horse, aiming toward ditches, brush piles, or neatly stacked poles, and cantering forward until hooves parted with earth and we sailed upward, buoyant for brief glorious moments.

Most of the time, this is not a point-and-shoot exercise. On TV it looks like the rider balances primly with her shiny boots in the stirrups while the horse bounds around the ring or through the field like a lamb, vaulting obstacles in a neat line. Inside the rider’s head, it’s a different story.

It’s all about timing, the length of a horse’s canter stride and how many of those 3-beat strides fill the space between one jump and the next. If it’s a tricky distance, you might go faster or slower to shorten or lengthen the stride. Just as you’re taking off, you shift your weight forward and slide your hands up his neck a bit, loosening the rein so you’re not jabbing him in the mouth as he stretches over the jump. Would a horse naturally do this on his own? Generally, no, not even to escape an enclosed pasture. Horses are by nature fairly lazy and would much rather swish flies and graze in a sunny field all day.

On one sticky Florida afternoon, I navigated through a cross-country course with obstacles made from tree trunks and other “natural” barriers. My horse was a stocky palomino with a mid-section like a barrel. He had been a poky western pleasure mount before arriving at  the farm in his reluctant new role as a hunter jumper, and his strides were clipped, his manner resentful, and his driving force was to avoid exertion and retire to the stall as soon as possible.

the farm in his reluctant new role as a hunter jumper, and his strides were clipped, his manner resentful, and his driving force was to avoid exertion and retire to the stall as soon as possible.

My calves ached from the constant “encouragement” this horse required to make it up and over each jump in the field. He’d obediently break into a misleading canter, only to pull up short just before the jump and pop over it grudgingly from a stand still, leaving an unprepared rider wobbling in the saddle. Despite knowing this, I let my guard down at the water jump. It was just a two foot ditch flanked by railroad ties, like hopping a crack in the sidewalk. He could have trotted over it easily, and in fact, that’s just what I expected him to do. Pridefully, I thought, this one was easy. We all know what proverbially follows pride.

Inches before the simple jump, he stopped dead, planting his hooves like a mule. His muscled hind end gathered up behind him like we’d just roped a calf and he was in full skid. I continued on without him. In what I like to imagine was a graceful somersault, I tumbled over his ears and down, cracking my ribs across the railroad ties before flipping backwards into the water.

Icarus, fallen.

I lay on my back in the mud, feeling like a bird must after it has flown full-force into a plate glass window. Submerged, I looked up through about three feet of water, my arms pinned against my throbbing ribs by the solid sides of the jump. Thankfully, I did not try to breathe. I could not even gasp, as all air had been forced from my lungs on impact. A muted sort of quiet surrounded me, like when you sit like a yogi on the bottom of a swimming pool, testing how long you can hold your breath. The blue, cloud studded sky rippled overhead and I saw my horse’s nose as he peeked over the edge, certainly not concerned for my well-being, but more to inquire if we were now, in fact, done for the day.

In short measure, my companions rushed over to hoist me, dripping and muddy, out of the ditch. Rule number one is get back in the saddle. Never end on a bad note. So, up I climbed, each breath ragged and painful, and we approached the jump again. He gauged from my black mood that he should not repeat his little trick and skipped over it this time like he was in a girlish game of hopscotch. Afterwards, I sullenly led my horse back to the barn, water squelching in my boots the whole way.

For a time, while my ribs healed, my wings were clipped. It was one of those formative childhood moments: invincibility is imaginary. While I preferred the air to earth’s tether, the air was risky; lying face-up in a mud hole was always a possibility.

It’s tempting to cling to the sure thing, the comfortable, in lieu of that risk. Sometimes we even prefer our own painful mud hole to climbing out to face what might be humiliation or vulnerable exposure. It’s quiet in there, and we’re kind of used to it. We tiptoe along, watching others achieve goals, be adventurous, learn a new skill, go on that first date after a lost relationship, craft their art.

The view from down in the ditch is less than inspiring. We placate ourselves, pointing out the blue sky and sunshine, but it’s a stifled view we’re used to, settling for a rippling opacity, void of fresh air and birdsong. We cannot be afraid of bruised ribs or bruised egos. Take a breather after the hard knocks, but bruising is only a reminder of what not to do the next time. Because there should be a next time! We are not meant to be ditch dwellers. We are meant to test our mettle, reach beyond our grasp, experience abundance and taste what it is to fly, even without wings.

On a stifling hot June afternoon, we got married under a canopy of trees in a state park across the street from my parents’ house. After the promises and shy public kiss, we walked hand-in-hand down the aisle to the Beatles singing “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?”. I was barely 22. He was in the middle of vet school. He had hair. I had a waistline.

On a stifling hot June afternoon, we got married under a canopy of trees in a state park across the street from my parents’ house. After the promises and shy public kiss, we walked hand-in-hand down the aisle to the Beatles singing “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?”. I was barely 22. He was in the middle of vet school. He had hair. I had a waistline.